For more than a year and a half, the Michigan Technological University library and the school’s department of social sciences resembled a detective agency.

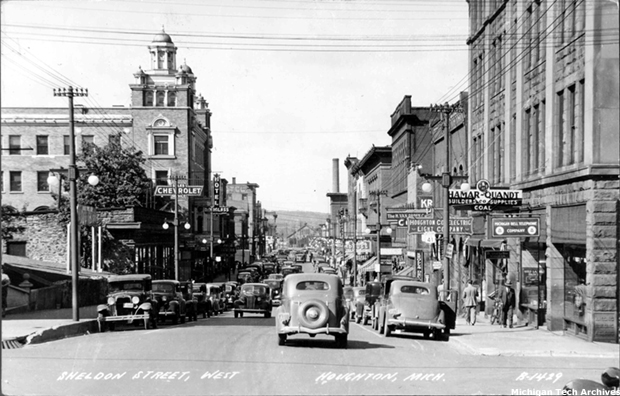

During that time, two staff members and three students carefully examined close to 11,000 historical images of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (UP), also known as Copper Country, to figure out if they could discern precisely where a photographer stood as the photo was taken. The context would provide richer information about a place’s surroundings, especially in circumstances where structures or environmental landmarks are no longer present.

More importantly, it was an opportunity for Bob Cowling, the school’s geographic information system (GIS) data librarian, to transform how people search for historical images. Searching by keyword terms relies on accurate metadata. If there isn’t good data governance from the organization managing the images, then the metadata could be missing important fields.

In addition, donated historical images often arrive without any dates or location information attached to them. The detective work involved in Cowling’s GIS project could give those photos a geographic place—and time—in history. The images would be easier to find on a map and make it possible to visualize what was there then, compared to now.

“This is challenging work, trying to not only determine the geographic location that this photo is showing but also, where was it taken?” said Cowling. “What is the vantage point? Was a photograph taken in the middle of a street intersection? Was it taken on top of a roof?”

The photos are part of the university’s Copper Country Historical Images (CCHI) database.

There were times when the students and staff in the group got lucky. Some of the photos had metadata—embedded data describing the image—to tell the group where it was taken. Others had visual clues like a pictured business or street name. Even then, creating a database of historic images based on where each photo’s photographer might have been standing involved more than placing a dot on a digital map and moving on.

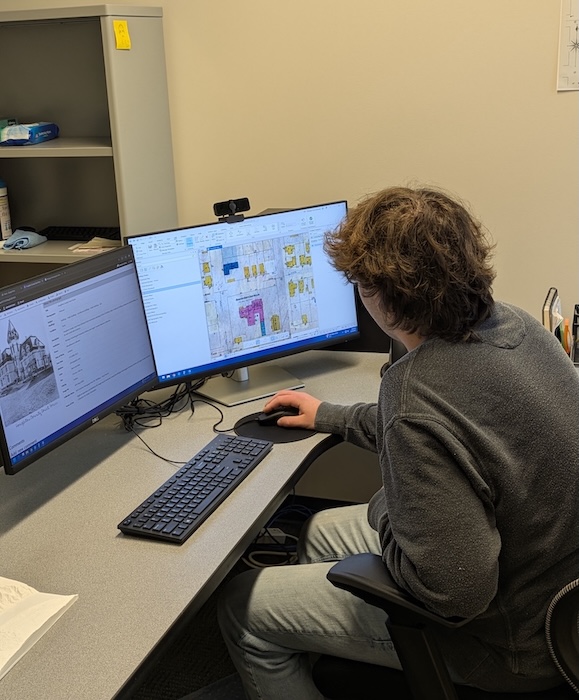

Using ArcGIS Maps SDK for JavaScript and Calcite Design System, and hand drawing vantage point views (the specific position or angle from which a camera captures a scene) in ArcGIS Pro, Cowling and his team added map-based discovery tools to the database. Now, archivists and anyone else who’s interested can search for images based on where they were taken.

Showing the Photographer’s View of History

Copper Country sits above Michigan’s more familiar, mitten-shaped lower peninsula and was once home to some of the world’s largest deposits of copper. When the Michigan Tech University archives first built its Copper Country images database in 2010, it was what you might expect: a collection of images searchable by keyword. Not long before Cowling arrived in 2022, it needed to be rebuilt on a new content management system because the existing system (Drupal 7) was no longer supported. He saw this as the perfect opportunity to elevate the user experience.

Many of the almost 11,000 images—such as photographs of people next to unrecognizable trees, or boats in open water—were impossible to identify by where they may have been taken. When the archivists got a picture of a street, an intersection, a building, or anything they could tie to a geographic location, then they had something to work with.

If the image didn’t already come with a detailed description in the metadata, the students on the team would look at historical fire insurance maps originally published by the Sanborn Map Company. Cartographers had hand drawn those maps in detail. So, if a picture featured a drugstore next to a flower shop on a specific street, students could reference an insurance map to see where two such stores may have been side by side.

From there, the group would try to determine the vantage point of the photographer. A student would look at the photo and compare it to the map to see what was visible. They would then manually draw a viewshed cone—which restricts visibility analysis to a specific horizontal and vertical angle—over the map in ArcGIS Pro to indicate where the photo was likely taken.

Ultimately, the students and staff members pinpointed the locations of 3,885 images. The group added any existing metadata to a spreadsheet, along with the year the photo was likely taken and an ID number to identify the photo. All data was loaded into ArcGIS Pro.

A Better Way of Finding History

Cowling has made it his mission to advance GIS use in archives and libraries. With an educational background in GIS, cartography, and library science, he worked in the Map and Geospatial Hub at Arizona State University to build a virtual representation—a digital twin—of the library to help users browse its maps and other materials without visiting in person. It’s the type of work that has inspired him to test the limits of what GIS can do in a library setting, moving searches beyond keywords.

For the Copper Country project, many of the maps came from the social sciences department’s Keweenaw Time Traveler project, which preceded the database’s upgrade. The Time Traveler project serves as a sprawling historical atlas of Copper Country, where a visitor can search for historical census records, maps, or user-submitted stories. Cowling made a mobile version of the database so that anyone exploring the area can look up what was there in the past while standing there in the present, via aerial images from the US Geological Survey.

When viewers search the latest Copper Country database using the CCHI Spatial Image Catalog, they first see a heat map showing where the most photos were taken in the early 1900s. Heat maps represent data by using colors to show data values. Zoom in, and the heat map changes to show more concentrated areas.

Cowling and his team are already working on their next image mapping project. The UP-Iron Atlas, built with Esri technology, will look at three areas of iron ore deposits: the Menominee, Gogebic, and Marquette iron ranges.

“Users are hopefully going to be able to see: What did these old towns look like? What did these old mines look like? The old rail? How did the iron get transported? Who lived in these areas?” Cowling said.

Like before, users will also be able to search for images on the map and see where the photographer was when they took the photo. This means that many images that arrived with little information may get a home—a time and a place—for the first time. As with the other project, it will make the historical database more valuable to archivists, researchers, and the public looking for additional geographic context about places or landmarks that may have otherwise been lost to history.