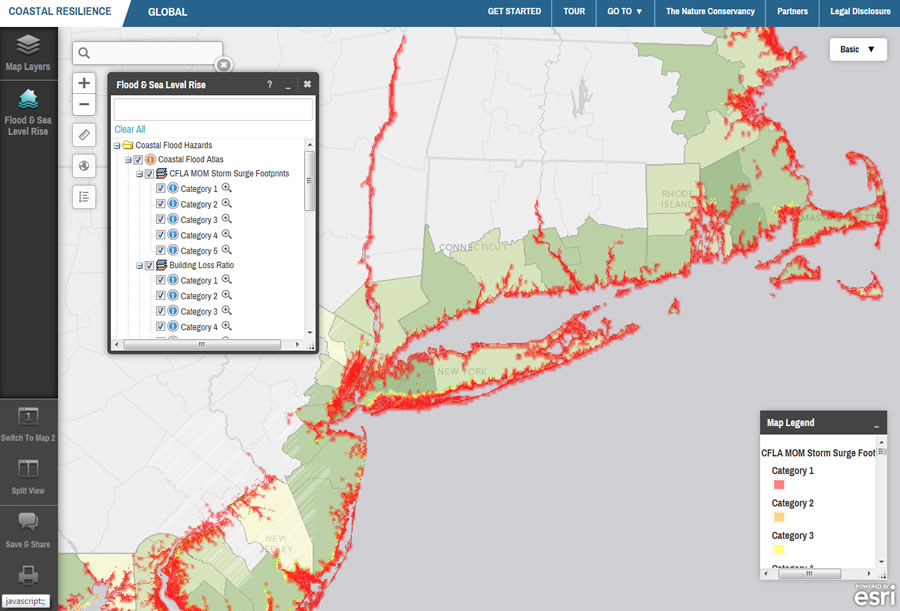

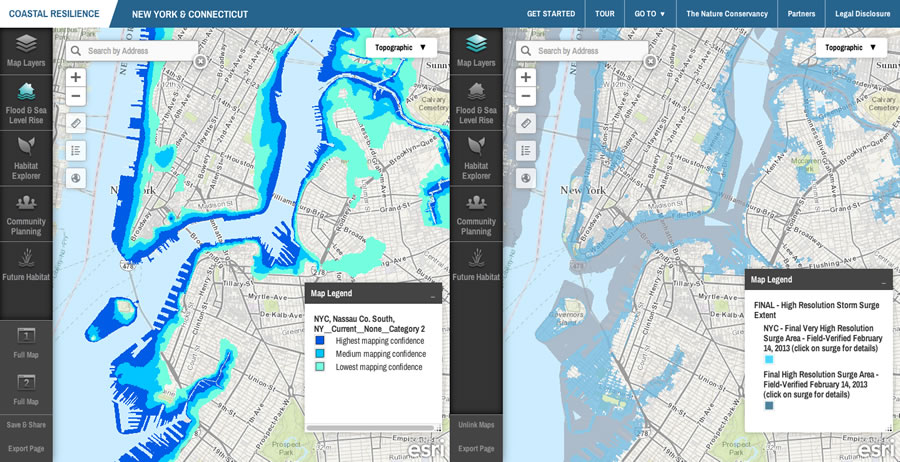

Thanks to a suite of online mapping decision support tools built by The Nature Conservancy and powered by the ArcGIS platform, government agencies and other organizations can examine how to prepare for and respond to storm surge and flood damage. The Coastal Resilience platform and suite of applications were introduced in 2008. Since then, they’ve been used for actual disasters big (Hurricane Sandy) and small (coastal erosion in the Puget Sound region of Washington).

Coastal Resilience helps users assess risk and vulnerability to storm surges and erosion along the coastlines of the United States, Mexico, and Central America and in the Caribbean. It also gives them ways to identify how to restore damaged or eroded land and adopt new techniques to protect vulnerable communities. Local and regional government officials, as well as the general public, can use the Coastal Resilience to respond to and prepare and plan for changing climate conditions and coming disasters.

Ready-Made Apps Mean Quick Deployment

Coastal Resilience was developed by a core group of partners led by The Nature Conservancy, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM), the United States Geological Survey (USGS), and the Natural Capital Project. These organizations wanted to make complex coastal engineering, risk, and land-use models accessible through a library of easy-to-use apps. They worked with the University of Southern Mississippi, the University of California at Santa Cruz, Ebert GeoSpatial, and Azavea to develop the apps using Esri’s ArcGIS API for JavaScript.

So far, using Coastal Resilience, The Nature Conservancy researchers have looked at how to solve different coastal management challenges, like flooding and coastal erosion. Researchers are able to emphasize nature-based alternatives, like tidal marshes and oyster beds, instead of seawalls and other man-made infrastructure. Deployed on the web, Coastal Resilience can be reproduced for looking at other specific coast-related issues easily.

“The tools’ platform and basemaps from ArcGIS Online support creating apps that can be designed to put social, economic, and coastal habitat data together alongside sea-level rise and storm surge scenarios,” said Zach Ferdana, a marine conservation planner at The Nature Conservancy. “People are now able to discover the spatial relationships that support mitigation and adaptation decisions.”

From Oil Spills to Oysters

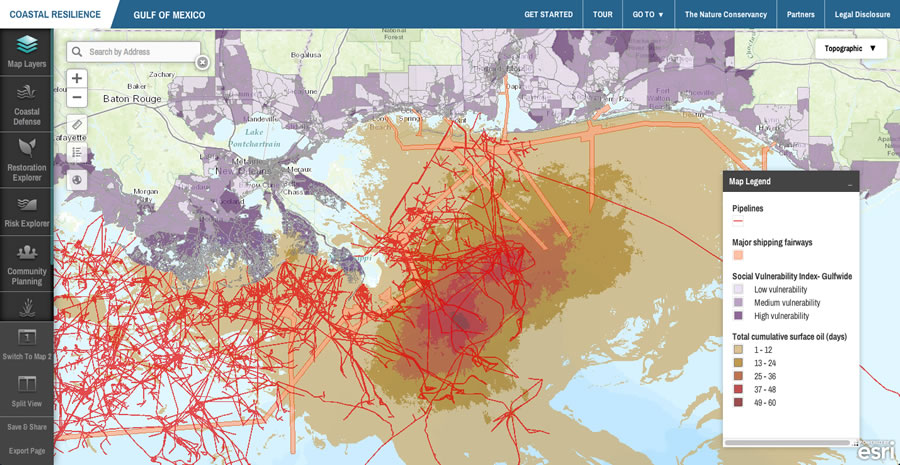

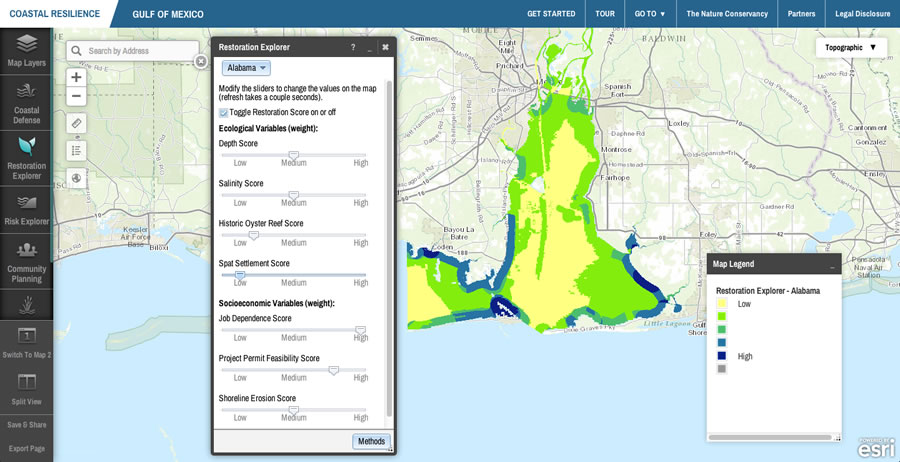

In 2010, Coastal Resilience was used to look at saving coastlines in Louisiana, Florida, and Alabama after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Almost five million barrels of oil spilled for 87 days, impacting 68,000 square miles of ocean and destroying wetlands, marsh grass, and coastal sand. To help bring back balance to the natural habitats and restore commercial fisheries, The Nature Conservancy and its partners developed an oyster restoration decision support app as part of Coastal Resilience in the Gulf of Mexico. This app, called Restoration Explorer, allows stakeholders to examine ecological and socioeconomic factors when restoring reefs.

The app includes a suitability index that was assembled using ArcGIS Spatial Analyst. Since oysters can only survive in water that is just right for them—at a particular depth, temperature, and salinity, for example—the index was created to weight cells on a raster surface with these factors for realistic restoration scenario planning. The factors can be changed depending on what is more important to the user when identifying potential restoration sites.

This app can be freely used by organizations that want to study scenarios for restoring oyster beds by going to the website and following the prompts. First, select a region: Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, or Texas. Then, move sliders from low to high to change different ecological and socioeconomic variables. If searching Mississippi, variables such as the current oyster reef, salinity, and historic oyster reef scores or the percentage of people employed in construction and natural resource industries in that area are available to study. The variables change according to the region.

As the variables are modified, the coastal regions that meet the criteria are highlighted. A description of the different variables and scientific methods used is available by clicking the Methods button on the main pop-up menu.

Even after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the app continues to be a tool to restore oyster beds along the coastline of the Gulf of Mexico. A project called 100–1,000: Restore Coastal Alabama uses the app to identify 100 miles of oyster reefs in Mobile Bay, Alabama, that will be restored and promote the growth of 1,000 acres of tidal wetlands. The project is related to legislation, called the RESTORE Act, enacted specifically to assist coastal Alabama after the Gulf oil spill.

“Restoration at this scale requires tools that look at the entire social-ecological system of the bay,” said Ferdana. “Restoration Explorer helps organizations evaluate the most suitable places that meet multiple management objectives.”

Defending the Coast

To continue protecting coastal communities that face natural and man-made disasters like the Gulf oil spill and Hurricane Sandy, researchers with The Nature Conservancy and other organizations are using Coastal Resilience to study how coastal habitats, such as oyster reefs, tidal marshes, and seagrass beds, protect communities from increased rates of coastal erosion. The app includes a coastal protection model that calculates an ecosystem’s ability to reduce wave height and energy, lowering the risk of erosion.”

Having these obstacles in front of the shoreline helps to reduce the energy in breaking waves,” said Ferdana. “We can be very clever, by forcing waves to break at a certain location, even, getting rid of most of their destructive energy.”

The Coastal Defense app has been used in locations such as Puget Sound, Washington, and at various locations in the Gulf of Mexico. Coastal watershed planners have used the app to reduce the risk of flooding by employing less invasive natural defenses such as marshes and oyster beds instead of creating man-made barriers. Planners can model whether to use man-made dikes (gray infrastructure) or natural marshes (green infrastructure) using the app. They are able to place infrastructure at a certain location along the coastline on the map and analyze the amount of energy in waves. Looking at different current and future scenarios in the app allows planners to find the most cost-effective and protective measures and determin where to implement green and/or gray solutions for the best outcome in protecting coastal communities.

“An added bonus, of course, is the increased fishery benefits,” said Ferdana. “We’ve really seen how much people and local economies are affected by disturbances in natural habitats or the lack of them. By protecting our resources and understanding how they can help stabilize the resilience of these coastal communities, we can provide a better community for nature and the people who live there.”

Coastal Resilience is now available in 10 US states: Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, California, and Washington; Central America: Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras; and the Caribbean: Grenada, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and the US Virgin Islands.

There are also global and US national web maps that together form the Coastal Resilience network. These and other stories can be found at http://coastalresilience.org. For more information, e-mail coastalresilience@tnc.org.