Games Created with ArcGIS Teach Disaster Management and Resilience Skills

Situations such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have heightened interest in the importance of disaster management and mitigation. Researchers at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in New York recently used ArcGIS to create two new serious games that can be important learning tools for responding to, mitigating, and recovering from calamities ranging from hurricanes to pandemics.

In doing so, the researchers have tapped into a new trend—the gamification of GIS. One aspect of this is using location data and GIS technology to develop realistic, 3D immersive scenarios in what are known as serious geogames for training, science, and education. These games often use avatars, giving the players a first-person perspective as they work through solving a problem.

A group of professors, cooperative-education students from RIT, and National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded college students from other universities across the country developed two serious GIS games for disaster resilience research using open data and the 3D modeling software ArcGIS CityEngine. The games aim to teach general audiences, emergency managers, and first responders spatial thinking skills and then use that knowledge to help communities withstand and recover from disasters.

“There is a lack of spatial thinking in the emergency practice right now, even though it can be really useful for identifying vulnerable populations, moving people to safe locations, and learning about how disasters impact areas,” said Brian Tomaszewski, lab director of the Center for Geographic Information Science & Technology at RIT, who led the projects. “I think using gamification to make learning spatial thinking more engaging is a great way to get people thinking.”

Games Mimic Real-Life Incidents

The serious games the team developed, called Project Lily Pad and Project EOC are both based on Hurricane Harvey, a category 4 storm that battered Texas on August 25, 2017. Harvey caused catastrophic flooding, more than 65 deaths, and $125 billion in damage, according to the National Hurricane Center.

Research for the games began during two NSF-funded Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) sites in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for Disaster Resilience Spatial Thinking, hosted at RIT in the summer of 2018 and 2019. The REUs were led by Tomaszewski, who is also an associate professor in the School of Interactive Games and Media (IGM) at RIT.

The 15 students in the REU investigated maps, data, and survivor testimony to better understand the disaster. By combining elevation models and flood data, the group was able to create accurate 3D city models of Galveston County and Dickinson, Texas, to use in the games. (Dickinson, which is in Galveston County, suffered major flooding and damage from Hurricane Harvey.) The groups used GIS data from OpenStreetMap, along with Esri tools, to create their interactive maps.

ArcGIS Pro allowed the team to collect and process publicly available data from Galveston County, such as shapefiles of building footprints. After the datasets were processed in ArcGIS Pro, they were then incorporated into CityEngine for 3D model development and eventual import into the Unity game engine.

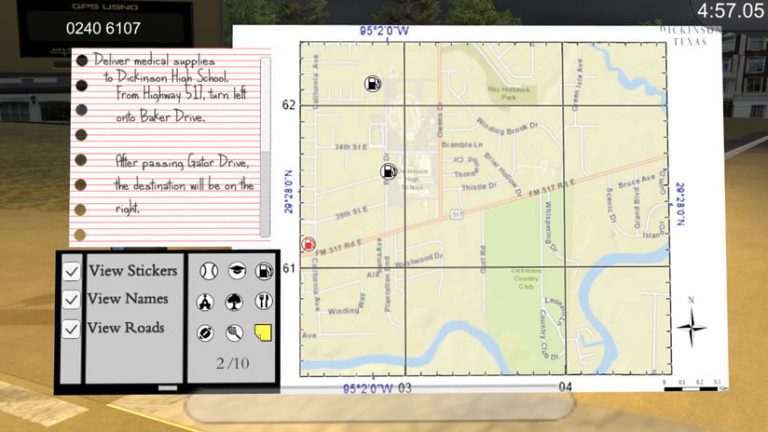

In the game Project Lily Pad, players first take on the role of a first responder in Dickinson. Players use a paper map to locate places to drop off supplies and navigate unfamiliar territory. Tomaszewski explained that during Hurricane Harvey, many of the National Guard members called in were new to the area, possibly making it harder for them to navigate the streets.

In day two of the game, the player’s avatar is an informal volunteer from outside Dickinson who takes a boat through flooded streets to conduct search and rescue operations, much like the Cajun Navy did during Hurricane Harvey. Players must rescue people and drop them off at higher-elevation safe havens equipped with resources—locations that are known as lily pads.

“The term lily pad was actually used by first responders during Hurricane Harvey in Galveston County and was the inspiration for the game’s name,” Tomaszewski said.

The Project Lily Pad game helps volunteers and National Guard members—especially those coming in from other areas—familiarize themselves with the geography of the neighborhoods so they can respond more quickly when dropping off supplies or rescuing people.

“While responders are waiting to deploy at a disaster zone, they could play a game like this to familiarize themselves with the local environment,” said Tomaszewski. “It’s also useful for any audience, as it teaches spatial thinking skills with respect to flooding and hurricanes.”

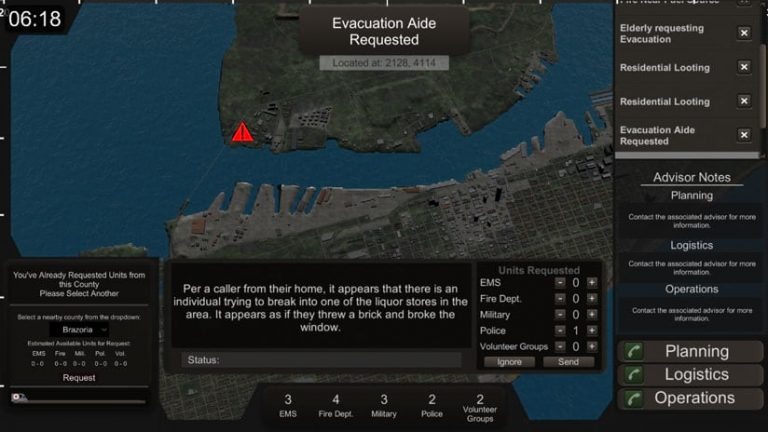

In the Project EOC game, players take on the role of an Emergency Operations Center (EOC) manager in Galveston, Texas. As different disaster scenarios take effect, the player must make resource management decisions to control the situation, including deploying ambulances, police, and firefighters. Project EOC was created using a combination of Esri tools that included ArcGIS Pro for processing publicly available data that was then sent to CityEngine to create models for use in Unity.

In 2018 and 2019, some members of the REU group traveled to Galveston County to collect field data that could be used in the game. They learned about how the hurricane impacted Dickinson, conducted interviews with survivors, and identified buildings that were still in need of repair. The group also worked with Galveston County Emergency Management professionals to conduct evaluation assessments of the games.

“We learned that this game could be a really useful supplement for the tabletop exercises that many EOCs do,” said Tomaszewski. “Having a virtual game could be more scalable, cost-effective, and flexible for all of the people that are involved with these exercises.”

Gamifying GIS Data With help from six RIT game design and development co-op students and David Schwartz, a professor and director of IGM, the geospatial data came to life as immersive, open-source games.

Jeshua Johnson, a student at the University of Texas, Austin, who participated in the REU at RIT, was also part of the team that helped turn geospatial data into a 3D game environment. The process involved modeling the terrain and buildings and locating areas of interest for the game events, including the flood reports.

“Not many games are made with research as the focus,” said Johnson, who is majoring in arts and entertainment technologies and minoring in geography. “Project EOC was an opportunity to approach games from a different perspective that has the potential to really benefit society.”

The students started with GIS data from the Houston-Galveston Area Council, including building footprints, roads, and elevation data. After importing this into ArcGIS Pro, the data was edited to fit the area of interest for the project.

The data was then exported into CityEngine, where the procedural generation was utilized to generate 3D shapes, textures, and elevation.

“After initial generation of structures within the area of interest, we modified key structures throughout the area to better represent building heights in the Galveston/Texas City area,” said Johnson. “These models were then exported as .fbx files to be imported into the Unity game engine.”

The computer animation and modeling software Maya was used to create the building and character assets. It was then brought into the Unity game engine.

To design game play elements, the ArcGIS dataset was referred to again to correlate additional data related to flood reports and the location of key infrastructure such as energy plants and hospitals.

“I was brought on to work on the underlying systems that controlled game play, such as triggering disasters and tracking progress behind the scenes,” said Alexander Amling, a third-year game design and development student at RIT. “I really enjoyed working on a research-driven, practical project alongside researchers with backgrounds that were very different from my own. I found the entire experience to be a great way to explore the more academic side of software development.”

Project Lily Pad and Project EOC are free to play. You can download the games on GitHub or follow the instructions on this RIT web page.

For more information about GIS gamification, read this blog post by Chris Andrews, group product manager for geoenabled systems/smart cities/3D at Esri.

The video workshop High-End 3D Visualization with CityEngine, Unity, and Unreal, which was recorded at the 2019 Esri Developer Summit, is also available. For a look ahead at Esri’s plans to integrate ArcGIS into the Unreal and Unity gaming engines, watch this video from the 2020 Esri Developer Summit.