While most users experience the GIS through its user interface, most developers know that there are often additional APIs available that can be used to create solutions to solve business requirements. In this article we will be looking at one example of how a feature hidden right below the surface can be used to solve some unique challenges faced by utility customers.

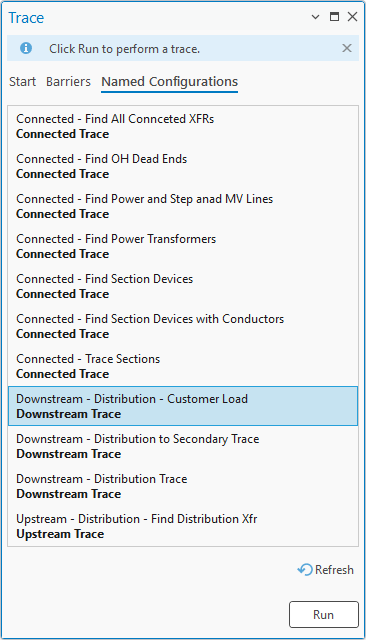

One of the first functions that a user is introduced to with a utility network is its ability to trace. You are typically introduced to this capability in the form of a trace configuration, a pre-packaged form of analysis created by an administrator to make your life easier!

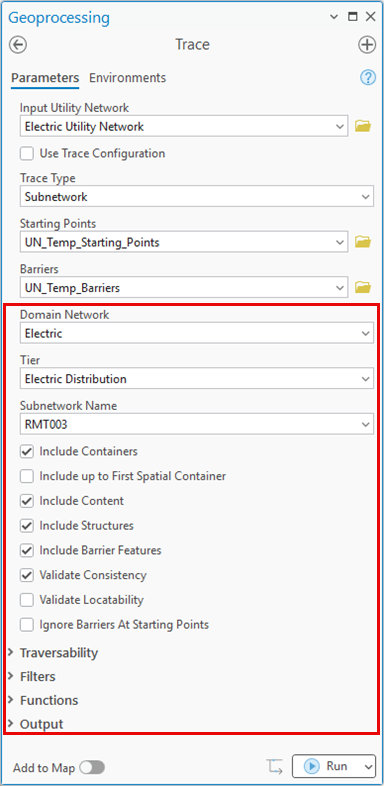

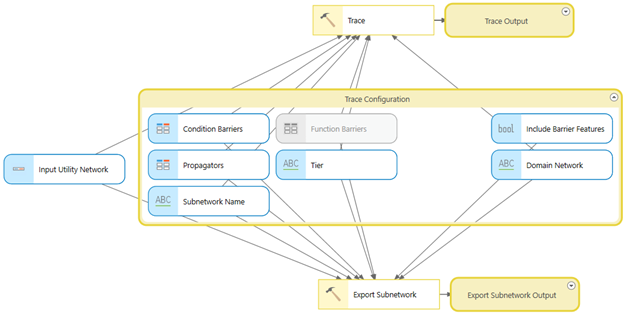

Once you start wanting to answer unique questions you will start using the Trace geoprocessing tool to create your own trace configurations to control the behavior of the trace and even how the results are output. One important example of this are the parameters used to define the trace configuration. These parameters are visible on the trace tool.

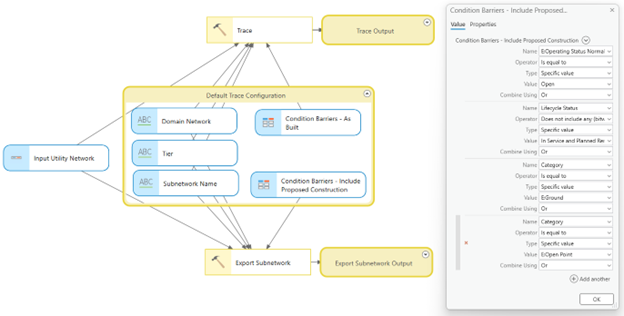

At some point, some users may want to use these trace configurations when creating exports for other systems. Maybe they want to extract a file that doesn’t contain customer information, or they want to configure the trace to include proposed construction in addition to features that are in service (this approach is discussed in the Design to operations article).

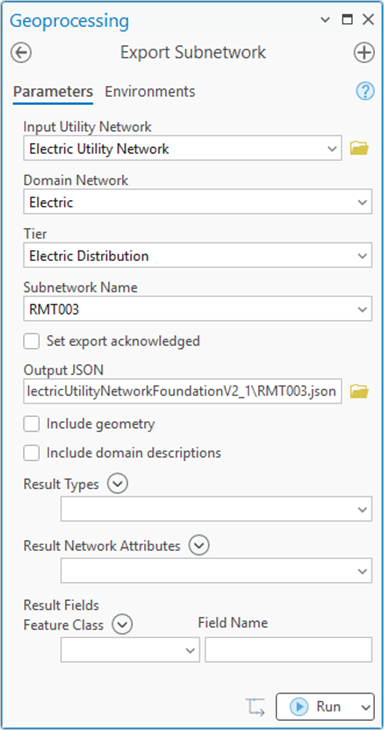

While it is possible to use the Trace geoprocessing tool to do this, some use cases may require that you use the Export geoprocessing tool because it is used to populate metadata (last export data) that records when a particular dataset was exported for use with another system.

At first glance this doesn’t seem possible because the Export Subnetwork geoprocessing tool doesn’t have parameters that let you control the trace configuration. This is because the default behavior of Export Subnetwork is to use the trace configuration from the tier’s subnetwork definition to perform the extract. If you look carefully enough, you will see that it is possible to do this, but it is not shown in the user interface because it is not something a typical user will need to do. One of the workflows is the one we mentioned above, needing to export information using a different set of criteria like needing to include proposed features.

Revealing what is hidden

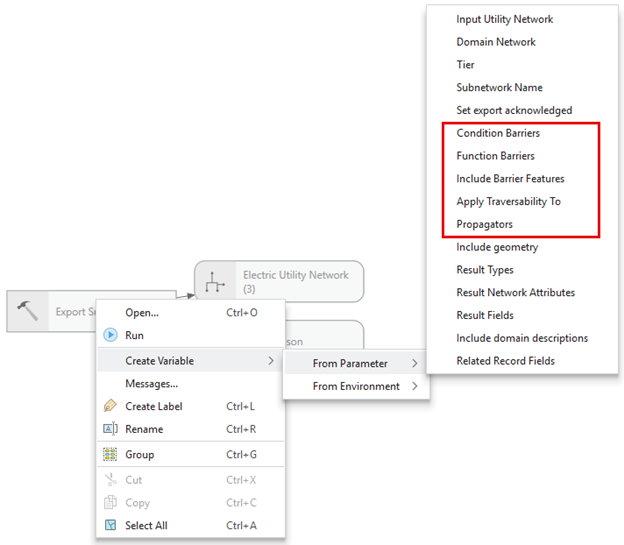

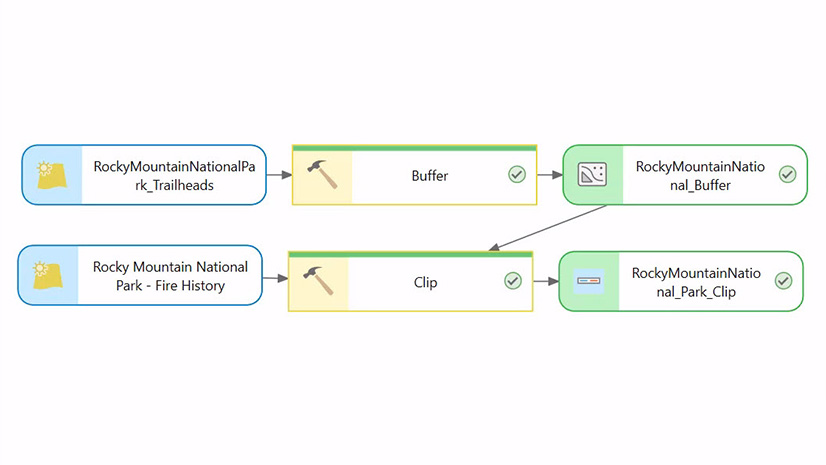

When trying to understand all the capabilities of the how to use a tool, there are several different paths to take. The most common way of doing this is for a developer to use one of the APIs Esri provides for interacting with the utility network (ArcGIS Pro SDK, ArcGIS API for Python, Arcpy, ArcGIS Enterprise SDK, or REST APIs) and see what capabilities and parameters each API provides for that function. For the purposes of this article, we will use Model Builder to demonstrate this example. This is because it provides a graphical user interface to the geoprocessing tool that allows you to access some of the hidden parameters only available via the various Python APIs. You can learn more about using Model Builder in ArcGIS Pro.

If you create a new model and add the Export Subnetwork geoprocessing tool to it, you will see that the interface for the tool appears the same. However, if you right-click the tool you will see a context menu that lets you Create Variables from the parameters of this tool. If you expand the parameter list, you will see that the tool has several hidden parameters available that correspond to the trace configuration.

If you turn these parameters into variables, you can then populate them with your desired values and use that to create the trace configuration used by Export Subnetwork. There are many ways to achieve this, but I’ve found one of the easier methods is to:

- Create a new Model

- Add the Trace geoprocessing tool to your model

- Open the Trace tool

- Populate the trace tool with the desired trace configuration

- Create variables for the trace configuration from the Trace tool in your model

- Add the Export Subnetwork geoprocessing tool to your model

- Point these variables to the Export tool

This approach allows you to use the UI from the Trace GP tool to define your trace configuration then use that trace configuration in export subnetwork. If you are using one of the other APIs you will find these parameters exposed there as well. One trick that can help you test populating these parameters is to look at the REST request that is generated when running these tools, this will let you see requests/responses like in this trace configuration example.

Back to our example from the Design to operations article. The workflow described in that article allows you to extract proposed, currently de-energized features. This is achieved by using a different set of condition barriers for each trace.

This functionality is critical to system operators, who need to import these proposed features into the system they use to create and manage switching orders. Having visibility into these proposed, de-energized features also provides them with the situational awareness they need that allows them to monitor the area as construction crews begin constructing and energizing this proposed equipment.

Conclusion

This article gives one example of a way that you can extend the capabilities of the utility network to support important business processes without writing any code. If you look closely enough your curiosity will be rewarded with many examples of capabilities like this. However, make sure you take your time and thoroughly read the documentation that comes with the tools and APIs we provide since these hidden features are typically hidden for a reason. They come with caveats, exceptions, or workflow limitations that must be thoroughly understood before you implement them in a production environment.

Commenting is not enabled for this article.