Landscape-level analysis for climate-smart agriculture

A nonprofit organization in Malawi uses GIS to apply sustainable farming practices that can improve crop yields for smallholder farms in this southeast African country.

The inland nation of Malawi is a small country but is densely populated. Nearly 80 percent of its people are smallholder farmers. On average, farms in sub-Saharan Africa are already the smallest in the world. Malawi’s farms averaging fewer than two hectares, are primarily planted with maize, and are dependent on rainfall. Given these limited resources, farmers are generally able to produce only enough to adequately feed their families.

Farmers’ limited capacity for taking on risk, coupled with limited access to sustainable technologies and financial services, further reinforces low agricultural productivity. These limitations produce a yield gap—the difference between potential and realized yields in the same geographic area. Depletion of soil nutrients, loss of trees, and other environmental impacts on agriculture can exacerbate risks to future food production. However, there is potential to reverse these trends and improve economic and environmental conditions in the country.

Agricultural production is directly linked to the well-being of people and the environment in smallholder farming communities in Malawi. Rising rural populations in areas with a fixed amount of cultivatable land are placing unprecedented pressure on environmental resources and ecosystem services and making it more difficult for farmers to derive their livelihoods from the land. To produce the greatest economic and social benefit, efforts to improve this situation must simultaneously address environmental impacts and agricultural productivity.

Nonprofit organizations are heavily involved in the mission to increase food production and restore natural capital in Malawi. They play a pivotal role in researching local needs, providing new technologies, and identifying novel implementation strategies. The Kusamala Institute of Agriculture and Ecology (hereafter, Kusamala), a non-governmental organization (NGO) located east of Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe, focuses on using local resources and knowledge to design climate-smart agriculture (CSA) strategies for central Malawi. CSA has multiple objectives: to increase agricultural productivity and incomes; adapt and build resilience to climate change; and—where possible—reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions.

Kusamala and affiliated researchers employ GIS technology, acquired through the Esri Conservation Program, to bolster and evaluate the impact of CSA in the country. In 2013, Kusamala received a grant from the Scottish government in partnership with the James Hutton Institute and Climate Futures. Over the next three years, the project will bring climate-smart practices to 1,500 households in the Dowa and Lilongwe districts of central Malawi, ultimately helping 7,500 individuals.

Planting the indigenous Faidherbia albida tree in fields, for example, is a climate-smart practice. Known locally as the magic tree, this tree fixes nitrogen in the soil, sequesters carbon from the atmosphere, provides fodder for livestock during droughts, has the unique ability to shed its nitrogen-rich leaves during the growing season (thus not competing with any crops), and retains its leaves during the dry season, providing shade for the bare soil.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations asserts that a landscape approach is needed to achieve the multiple objectives of CSA. Landscape approaches incorporate farming systems into landscapes in ways that capitalize on natural biological processes, recycle waste, and diversify farming systems. These approaches put less pressure on natural resources and minimize the need for fertilizers, pesticides, and other external inputs that can be expensive and harmful to the environment. GIS is the preeminent tool for mapping and analyzing natural and human-created processes at the landscape scale and thus is an important technology for CSA evaluation and implementation.

At the district scale, Kusamala used ArcGIS software to create maps for a collaborative workshop with local stakeholders. More than 20 organizations, including local and district governments and private and community groups, met for a three-day workshop focused on improving interorganization collaboration to enhance large-scale social and environmental benefits from CSA in Dowa District.

One of the first questions representatives asked was, “Who is doing what and where?” Rather than having different agencies carrying out similar projects in the same area, organizations could dovetail their efforts if they knew each other’s catchment areas (i.e., where each agency was working). Kusamala coordinated a participatory mapping process to collect each organization’s catchment area on paper maps. The catchment information was then digitized into ArcMap and the Count Overlapping Polygons tool used to enumerate overlapping catchment areas in the district.

The map illuminated areas that receive significantly more attention as well as areas that receive less attention. Mobilizing collaborative efforts to address problems that are interrelated is an important strategy for meeting the multiple objectives of CSA.

For example, the Farm Income Diversification Program seeks to sustainably improve the livelihoods of rural Malawian communities by diversifying farmer incomes. Similarly, one of the objectives of CSA is to diversify crops in farming systems. These missions align in purpose and geographic space and could be amplified by synchronizing efforts.

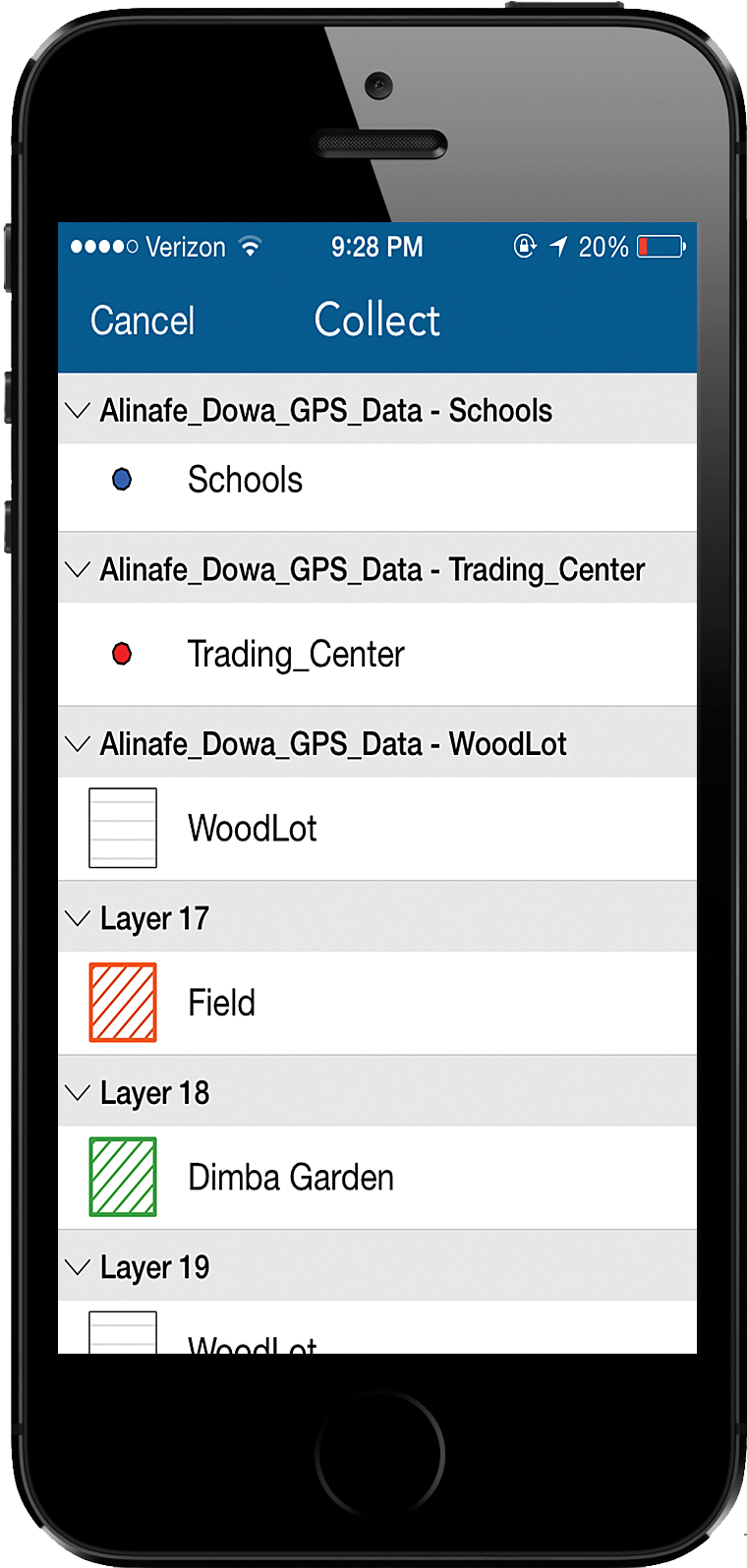

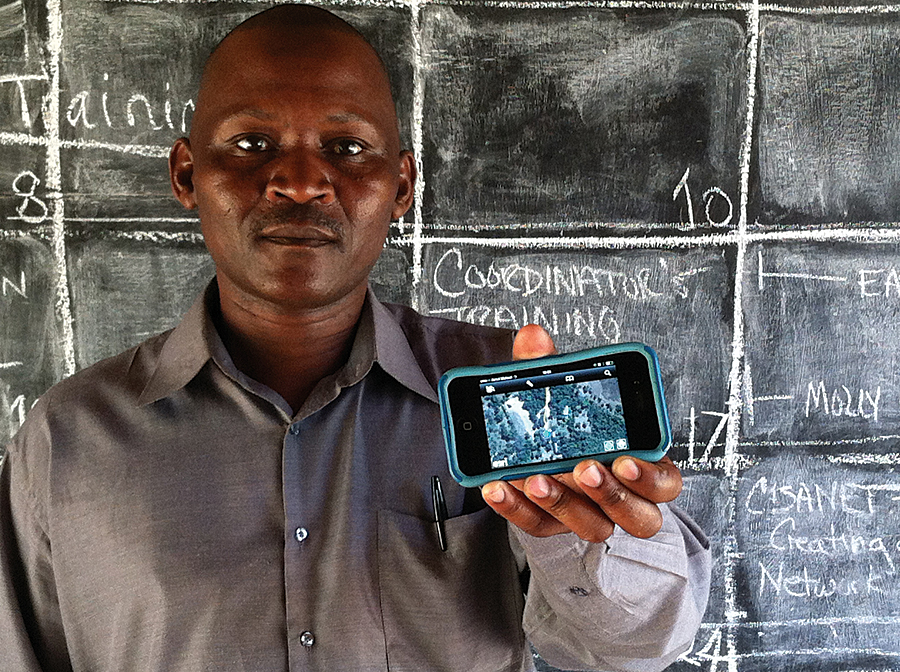

In 2013–2014, researchers at Kusamala explored how field arrangements impact CSA adoption by smallholder farmers. The Esri Collector for ArcGIS app was used on a tablet to collect GPS data for 10 farmers’ households, fields, and gardens in a rural community near Lilongwe, Malawi. Maps created from the GPS data illustrate the intentional scattering of farmers’ fields across the landscape.

The isolation of fields in this area plays an interesting role in smallholder communities. By scattering their fields, farmers minimize the risk that all their crops will be impacted by disturbances such as pests, disease, and fire. The rationale behind this prudent approach is that with many independent fields, some fields will produce even if others do not. With one large field, farmers risk starvation in the event of a low-yield year, even if that occurs infrequently. This diversification strategy used by smallholder farmers ensures that food production stays above a minimum threshold.

Scattering fields, however, reduces average yields relative to what could be obtained if fields were consolidated. Furthermore, the transportation costs associated with each field influence the amount of nurturing farmers give to crops. For example, fields far from a farmer’s house will not receive the same number of compost manure applications as nearby fields. Over time, this leads to nutrient depletion in distant fields. Coming to grips with this local heterogeneity and fragmentation of resources is important for planning the future of CSA in Malawi.

The CSA project will be monitored and evaluated using participatory video and mapping and GIS/GPS technology. GPS data will be collected for each of the 1,500 households that receive CSA training. Farmers’ perceptions of well-being, measured before and after the training, will be linked to the GPS data to visualize the impact CSA had in Dowa District. The Collector for ArcGIS app will be used to collect customized GPS data related to natural and social resources in the study area.

This data collection will enable researchers at Kusamala to analyze how perceptions of well-being are related to the proximity of natural and social resources such as forests and schools. “GIS will help us understand the natural and social resources we have in Dowa and Lilongwe districts and how we can best manage them,” said Chisomo Kamchacha, a monitoring and evaluation specialist at Kusamala. Ultimately, the analysis will provide a forum for international advocacy and produce information with the potential to influence national decision making.

ArcGIS software on the desktop, online, and on mobile devices provided powerful tools for visualization and analysis of CSA at the landscape scale. Kusamala continues to use geospatial technology for facilitating collaboration, research, and evaluation of the CSA project.

Additionally, Kusamala has acquired RapidEye multispectral satellite imagery for landscape-level vegetation mapping. “GIS puts Kusamala in a place where it can be a hub for innovation, research, and development,” said Kamchacha. The organization’s innovative use of GIS is novel in the Malawi’s NGO community. Kusamala’s story serves as a powerful demonstration of scalable use of GIS in the developing world that can be replicated.