ArcUser Online

Is Special Data Driving Your Fire Engine?

Finding, understanding, maintaining, and mapping special public safety data

By Mike Price, Entrada/San Juan, Inc.

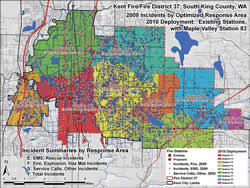

Kent Fire analysts use risk maps to compare primary station response capabilities to urban, suburban, and rural areas within the district.

This article as a PDF.

Every jurisdiction needs not only framework datasets, such as transportation and cadastral layers, but also highly localized datasets on facilities, infrastructure, and other assets. These resources, typically used on a daily basis, must often be captured or derived by local government. Having a strategy for acquiring, organizing, and maintaining this data is every bit as important as framework datasets.

This article builds on a previous article, "Is Data Driving Your Fire Engine? Finding, understanding, maintaining, and mapping spatial data for public safety." It presented Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) framework datasets that are often used by public safety service providers. In this article, the processes of Kent Fire Department in southern King County, Washington, were used to illustrate how these datasets are acquired and used. The six framework types discussed in the previous article and descriptions of typical data types and sources of the Kent Fire Department are listed below in Table 1.

Introduction to Special Datasets

There are datasets necessary for public safety activities that do not fit into framework categories discussed in the previous article. These are extensive datasets that responders use daily for mapping station locations, recent incidents, coverage areas, and protected values. Many non-framework or loosely connected datasets have also been included in this second group, which we will call special data.

| Dataset | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation | High-quality streets for time-based geocoding and incident geocoding | Kent Public Works, King County, TIGER 2009 |

| Cadastral | Assessor parcels with complete attribution | King County Assessor |

| Washington Public Land Survey System (PLSS) | Washington Department of Natural Resources | |

| Orthoimagery | High-resolution orthoimagery | Commercial providers |

| Political units | City, district boundaries, and urban growth areas | State, county, and municipal data providers |

| Elevation | 10-meter digital elevation model | U.S. Geological Survey |

| 6-foot LiDAR | Puget Sound LiDAR Consortium | |

| Hydrography | Stream centerlines, water body polygons, flood maps | U.S. Geological Survey and FEMA |

The scope, content, and sources of special data vary considerably. Many special datasets are generated and maintained by local jurisdictions using locally defined formats, styles, and standards. While framework data is closely aligned with FGDC standards for accuracy, scale, and completeness, special datasets are much more free form. These datasets typically meet the needs and answer concerns of one or several agencies. Their structure is typically defined by commercial software and data providers. Computer-aided dispatch (CAD) and fire service record management systems (RMS) are two closely aligned datasets that often vary considerably between jurisdictions, so sharing special data is not always easy.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) recognized the need for guidelines and standards for special data. NFPA recently formed a committee to evaluate domestic and international public safety data sharing needs. The Committee on Data Exchange for the Fire Service is now reviewing and preparing recommendations, guidelines, and standards for public safety data. In this article, special data has been divided into seven categories that will each be discussed separately. To provide a real-world example, the strategies and sources used by Kent Fire will be described.

7 Categories of Special Data

- Facilities

- Infrastructure

- Location and description

- Demographics

- Hazards

- Historic risk and program

- Modeled and derivative

Facilities—Essential and Critical

Facilities are locations and resources. Although they are usually fixed, they can sometimes be mobile. They contribute to or are affected by emergency response and public safety activities. Facilities can be divided into two subgroups: essential facilities and critical facilities.

One year's incidents, mapped and symbolized by type, provide excellent benchmarks to analyze response effectiveness and identify regions where very high incident loads might overwhelm assigned resources.

Essential facilities include services (e.g., apparatus, equipment, and personnel) to provide public protection and effect an emergency response. Critical facilities are major recipients of emergency assistance and have special needs during an incident. However, facilities are not always only essential or critical. A particular facility, such as a school, might fall under critical rules during one emergency, such as an evacuation or a safety lockdown, but during an evacuation sheltering scenario might perform an essential function. Table 2 contains a short and intentionally incomplete list of essential and critical facilities. Use local expert knowledge and intuition to add more valuable datasets to these lists.

Each of these facilities requires mapping and on-site assessment to determine the role, effectiveness, and interplay of these resources during an emergency. Facilities are often mapped as location points or parcel/building footprint polygons. Attribution varies by jurisdiction and facility. Fire stations include apparatus and staffing; schools list student and staff occupancies and available evacuation resources. As a critical facility, a hospital might list typical patient and staff occupancies, areas with special evacuation needs, and hazardous or controlled substances. As an essential facility, resources for trauma service, patient handling, and medical quarantine might be listed.

Kent Fire maps essential and critical facilities at the parcel and building footprint level. For location points, aerial imagery allows points to be placed at front doors or street entrances for facilities such as fire stations. Attribution varies by facility type. Essential facility data includes available resources, such as equipment and personnel, contact information, and staffing schedules. Critical facilities information includes populations at risk, temporal occupancy data, contact information, and emergency response plan links.

| Essential Facilities | Critical Facilities |

|---|---|

Fire stations |

Public buildings |

Infrastructure

Infrastructure can become a very broad category. In the fire service, water for fire suppression quickly comes to mind, but there are many more infrastructure players to consider. Table 3 lists several infrastructure types and the associated datasets that are important for Kent Fire.

The Kent Fire Department maintains a close relationship with the Kent City Public Works Department, the primary water provider within the city. Data is updated and shared regularly, and neighboring water companies provide hydrant location and testing information. Prefire plans include information about buildings with sprinkler systems.

Emergency communications are managed by Valley Com, a regional center located in Kent's southeast suburbs. The communications links between agencies are tested regularly and are always improving. The regional center maintains call lists and radio frequency information for commercial service providers and utility employees who often participate during emergency drills. The Kent Fire Public Information Office has developed excellent relationships with the media and citizens in the fire district.

Kent Fire supports close relationships with commercial utility providers throughout its jurisdiction. Appropriate information is carefully shared and incorporated into emergency response plans. Utility data often includes secure, private information, so special arrangements between the two organizations protect sensitive information.

Fire Suppression Water Supply

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Water sources and storage | Reservoirs, wells, tanks, and towers |

| Water distribution system | Pipes, pumps, valves, pressure regulators |

| Water delivery systems | Fire hydrants, fixed fire protection (sprinklers) |

Communications

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Emergency services communication | CAD center, emergency operations center, repeaters, portable and fixed radios |

| Public telephone | Land line and cell towers |

Utilities

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Culinary water | Location, quality, and security, emergency backups |

| Electrical service | Distribution systems, service areas, emergency backups |

| Gas service | Distribution systems, service areas, emergency shutoffs and shutdown procedures |

| Sewer, storm sewer system | Collection systems, treatment facilities, environmental sensitivities |

Location and Descriptive Information

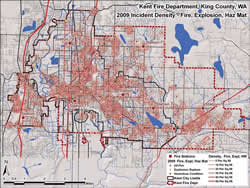

Incident density, or "hot spot," maps show where fire, explosion, and hazardous materials incidents occur with greatest frequency.

This category can become a catch-all for a variety of data. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between a critical facility with very special needs and a target hazard exhibiting lesser hazard or risk. This data has location or position information that is important to public safety mappers. Data types are typically points or polygons. Data sources can include assessor parcels, fire preplans, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) inventories, or similar datasets.

Important location-based data might include

- E-911 address points

- Target hazards

- Cultural values

- Areas of critical environmental concern

Kent Fire works closely with the King County E-911 office to maintain a complete, current E-911 point set. Information collected from assessor parcels, building footprints, building permits, and field inspections keeps this data current. Kent Fire uses this point data as the source for its first order incident geocoding address locator because this data places incident points directly on the involved structure.

Demographics

Demographic data is often the best way to identify which resident populations are at risk. The U.S. Census Bureau updates block-level statistics every 10 years. It is 2010, and Census 2000 data is out of date in many parts of the country. Kent and other agencies anxiously await the release of this 2010 data. In the interim, locally collected summary information is used to update census population counts. Many regional associations of governments estimate annual population increases for municipalities, but it is much more difficult to determine growth within special districts that do not match city boundaries. Growth studies often use Traffic Analysis Zone (TAZ) projections to estimate future population in reasonably small areas. At the local level—and until Census 2010 data is released—emergency service planners use a variety of spatial and tabular information to update current populations and estimate future growth.

Sources of demographic data might include

- U.S. Census Bureau

- Community census updates

- Business statistics

- Building permits (both issued and finalized)

- Planning and community growth projections

- Local expert knowledge

At Kent Fire, GIS analysts filter current assessor parcel data to separate single family from multifamily dwellings. Building permits, fire preplans, and housing authorities provide multifamily data including unit counts and occupancy rates. Once the unit count is established, Census 2000 block records provide typical family composition throughout the jurisdiction. Population summaries are performed at the census block level and compared to city- and districtwide estimates for validation.

Hazards

Hazard data often comes from various federal, state, and local sources. Typical hazard types might include

- Commercial and industrial hazards

- Cultural hazards

- Natural and environmental hazards

- Land use and land cover (existing and proposed)

- Zoning (existing and proposed)

Kent Fire maps and analyzes many sources of hazard data, including Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) floodplain mapping, parcel-based occupancy data, EPA hazardous substance inventories, insurance service data, and site inspection notes. Earthquake, lahar (volcanic mudflows), terrain, slope failure, and other hazards come from U.S. Geological Survey, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources Geology and Earth Resources Division, and private studies. Hazardous inventories and substances on-site are mapped from EPA Tier II (chemical inventory) data, Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) Title III material safety data sheets, and site inspections.

The department protects a major interstate highway corridor, two major railroads, and the second largest warehouse facility on the West Coast of the United States. Hazardous substances that are being stored or transported in the county are monitored through shipping documents and on-site storage information. Kent Fire supports a geographically distributed and highly trained Hazmat response team. King County and Kent City land-use and zoning maps identify areas where hazardous occupancies often cluster.

Historic Risk and Program Data

For many emergency service agencies, the number one item on a special data list has been historic incident and response data. This information is essential for mapping response activity, measuring performance and risk factors, and assessing program development. Emergency service mappers geocode and analyze incident response data to understand program effectiveness, overload, and limitations. Incident-level data provides an incident location, incident type and severity, and time stamps that monitor the overall incident from call received to call complete.

Apparatus-level records include time information for each responding unit including when it is notified, how long it is en route, time spent on the scene, time when the scene is released, and the time in service. Apparatus data identifies the response time and capabilities of the first unit on scene and tracks the arrival and departure of all dispatched units. Postincident analyses recall when full concentration (i.e., sufficient apparatus) and a full effective response force are reached at the scene. Historic incident data reveals possible gaps in service in space and time. It provides invaluable baseline data for program tracking and modification, including performance studies, growth analysis, and public awareness/reporting. Incident analysis is a fundamental piece of the Standard of Coverage (SOC) study, now performed by many agencies to measure level of service and demonstrateto government officials and the public that the department is effective.

Risk and program data typically includes

- Historic emergency responses (by incident and apparatus)

- Fire inspections and preplans

- Special studies

The Kent Fire Department obtains incident data in real time from Valley Com. All information is transferred into the department's RMS for inspection. Once addresses are standardized, call types confirmed, and time stamps verified, the incidents are geocoded, mapped, and analyzed. In 2009, Kent Fire was reaccredited by the Center for Public Safety Excellence (CPSE). Historic incident data, analyzed to demonstrate agency performance and improvement, played a key role in the reaccreditation process. Kent Fire also monitors risk through special studies, including multiple responses to the same address, suspicious fires, and frequent false alarms. These studies guide fire operations planning and fire prevention programs.

Modeled and Derived Data

After obtaining and validating a variety of framework and spatial datasets, public safety GIS analysts create even more data. These derived datasets might include

- Primary station response areas

- Emergency response

- Operation plans

- Mutual, automatic aid relationships

- Growth analysis

- Capital facility plans

- Standard of coverage

As they assemble information, Kent GIS analysts apply many standard and innovative workflows to analyze data. They will compare and contrast data reflecting value, hazard, and risk with levels of protection. They monitor growth within the community and carefully plan for today's operations and for the future.

Recent ArcUser articles include many examples of public safety modeling that use actual data provided by Kent Fire and address topics such as the fundamentals of planning, preparedness, response, and recovery; the use of data for master plans and capital facility plans; planning operations; and assessing and presenting performance measures.

On April 27, 2010, southern King County voters approved a proposition that merged the Kent Fire Department and Fire District 37 into a new Kent Regional Fire Authority (RFA), effective on July 1, 2010. The new Kent RFA continues to provide the highest level of fire and emergency medical service throughout the cities of Kent and Covington and in unincorporated areas of King County previously within Fire District 37.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes the department all the best and thanks its staff and officers for the exceptional assistance and support they provided for public safety mapping; modeling; and, of course, data management.

Recent ArcUser articles on performing public safety modeling