Over the next decade, the earth will undergo dramatic social and environmental change. This means that a large number of people—perhaps 10,000—will need to be knowledgeable about the world and the analytic and synthetic methods of geodesign (multidisciplinary design at a geographic scale).

The most efficient way to achieve this is to educate today’s university students in these matters and do it in a manner that enables multidisciplinary collaboration and mutual learning not only inside the university but also across institutions and nations. That is the aim of the relatively new International Geodesign Collaboration (IGC), whose members include teams from universities around the world. It is a bold goal.

The International Geodesign Collaboration (IGC) focuses on a specific and exceptionally complex problem: how to identify and share the lessons and practices developed by a globally dispersed array of experts so the resultant knowledge can be leveraged to solve our most pressing societal and environmental needs.

Harvard University professor emeritus Carl Steinitz first aired the idea for the IGC at the Esri Geodesign Summit in 2015 and then again in 2016. In January 2018, the rest of us—University of Georgia geodesign professor Brian Orland, University of Minnesota professor emeritus and director of the Minnesota Design Center Tom Fisher, Esri project manager Ryan Perkl, and Esri global education manager Michael Gould—agreed to organize the collaboration. By March 2018, via invitation and word-of-mouth promotion, research teams from about 90 universities had joined the IGC.

The IGC focuses on a specific and exceptionally complex problem: how to identify and share the lessons and practices developed by a globally dispersed array of experts so the resultant knowledge can be leveraged to solve our most pressing societal and environmental needs. Coming up with solutions will demand deep integration across the traditional expertise residing in the physical, natural, and social sciences. These solutions will also need to be articulated through the landscape- and city-shaping skills of planners, designers, and engineers.

The IGC is interested in how multidisciplinary teams in multi-institutional and multinational groups consider and respond to the environmental, economic, and social impacts of development and change happening in natural and increasingly engineered systems, while taking into account cultural and governmental differences. Almost every university in the world studies these issues. Yet each university and each unit of government acts in its own set of geographies and societies, with its own content, definitions, methods, languages, color codes, and representation techniques. This makes it extremely difficult to compare otherwise related projects and learn from each other.

To ensure that comparisons and mutual learning can take place much more easily, the IGC seeks to greatly increase sharing and the standardization of communication across those boundaries. We believe that a central aspect of effective global collaboration and eventual action is—and will continue to be—public understanding of complex issues. Furthermore, that can and must be accomplished without using professional or scientific jargon.

Under the umbrella of this broad goal, the IGC has a number of specific objectives. They include the following:

- Through repetition by multiple teams, reveal fundamentally important design responses that cut across national boundaries and are less influenced by local political concerns.

- Use global-level geodesign studies to address national, regional, and local needs at the space and time scales of larger, longer-term societal and environmental issues.

- Publish and exhibit open-format work internationally in both English and machine-translatable local languages.

- For public education, build a library of shared resources around the design and planning issues that matter most for society and the environment.

- Educate future leaders who are capable of organizing and managing geodesign at global, national, regional, and local scales.

A key observation driving the IGC is that universities’ current methods of sharing tend to obscure rather than enable collaboration. People use their own idiosyncratic map layouts, highlighting specific items of local interest, with graphic and cartographic conventions that are determined by either national standards or personal preference. Project areas are usually complex polygons that sometimes—but not always—include a contextualizing buffer of the parts of the surrounding landscape that influence and are influenced by the project itself. Moreover, while a project’s expressed intent may be to solve problems that have global consequences, people rarely reveal the assumptions they’ve made, which makes it difficult to compare and learn from each other.

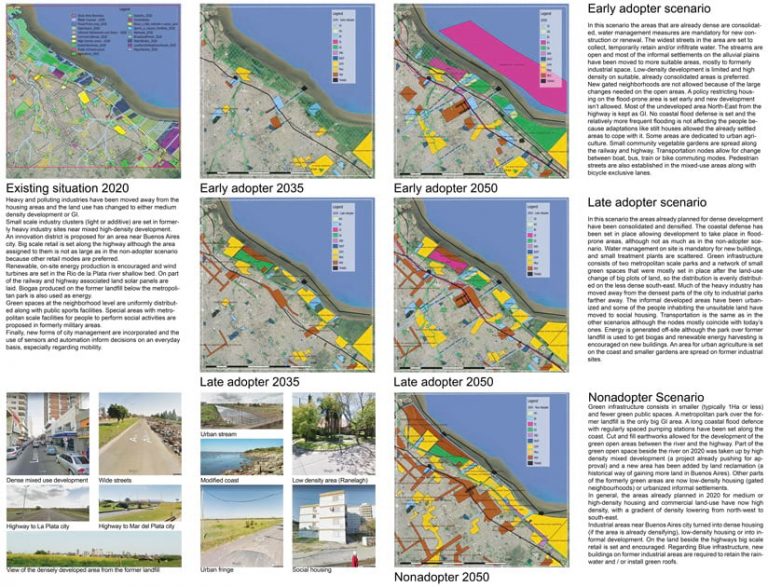

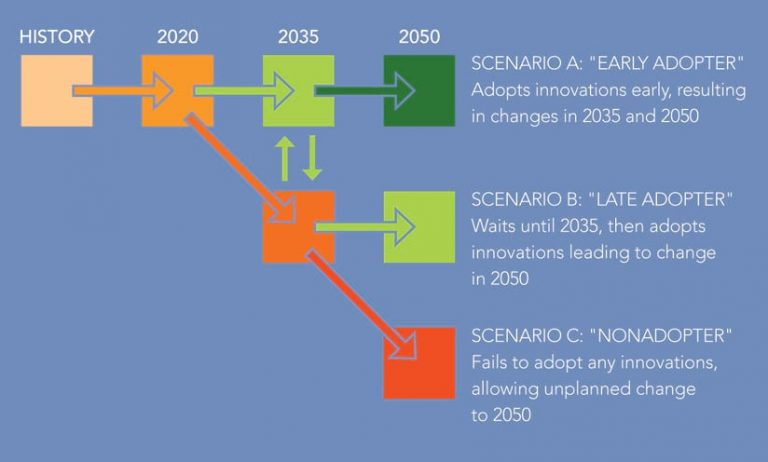

In hopes of combating the shortcomings of contemporary research, the IGC asked its current member teams to map a region of their choosing and show what might happen if decision-makers adopted a set of innovative environmental policies early, in 2020; late, so not until 2035; or not at all, continuing business as usual until 2050. Adopting IGC-generated assumptions about expected change in systems such as infrastructure, agriculture, and urban development, the teams then assessed the potential impacts on their study areas in 2035 and 2050, updating, in a few iterations, what their regions might look like at each check-in year.

To enable comparison among the diverse studies, the IGC introduced some organizing principles that enable different projects to express similar ideas in the same ways. Project participants had to adhere to the following:

- Select one or more square study areas that correspond to a scale of standard escalating sizes: 0.5 x 0.5 kilometers, 1 x 1 kilometer, 2 x 2 kilometers, 5 x 5 kilometers, etc., all the way up to 160 x 160 kilometers.

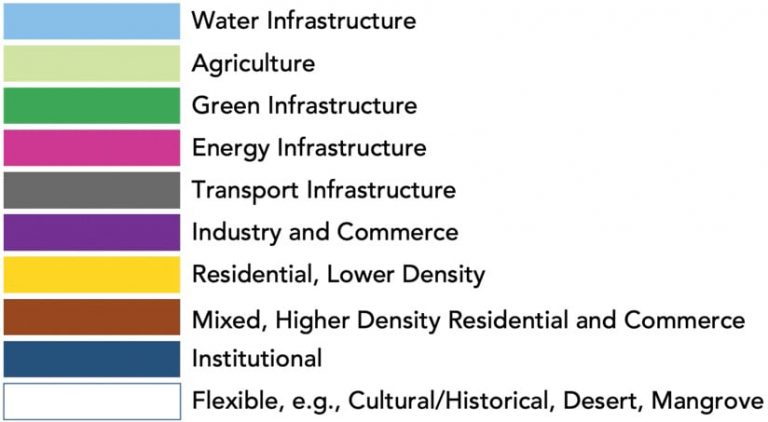

- Adopt nine agreed-on IGC systems—such as green infrastructure and industry and commerce—with the option of a 10th, locally relevant one as the basis for their scenarios, and represent these in an agreed-on color code.

- Identify and implement innovations that address the challenges facing each region.

With assistance from Esri and Geodesignhub.com, participating schools acquired software and minimal support for a range of key tools at no cost. Beyond that, they had to supply their own technical support. All results had to be ready to present in map form, in a common graphic format that included explanatory text and charts, and in English by the first IGC Summit, which coincided with the Esri Geodesign Summit this past February.

Each team defined its own project. Adapting systems data and models to local conditions, participants scaled and parameterized the assumptions and projected regional innovations to their specific areas.

Since every team followed the IGC’s recommended graphic layout, which was based on consistent square study areas, it was possible to compare like with like. Thus, even though the projects covered widely dispersed locations in 37 countries, the overall results showed that there is a cost to—and very little to gain in—not enacting any environmental policy changes now (i.e., in 2020). Given these conclusions, project participants were able to outline the most important steps that decision-makers need to take in each region.

The teams presented their conclusions to each other at the 2019 IGC Summit. Since everyone followed a specified design process and adhered to the same constraints, they were able to share their experiences at a depth of understanding that has never been available before.

Building on this momentum, the IGC is continuing to develop and grow. At the 2019 Esri User Conference, the organization’s work was featured in the Map Gallery and in a special session. Esri Press is also putting together a book about the organization and its initial project.

Currently, IGC membership is at well over 100 schools. The goal is to have at least one university from every country and major region represented. Please help spread the word so that more people around the world can apply the principles of geodesign to the challenges confronting their regions.