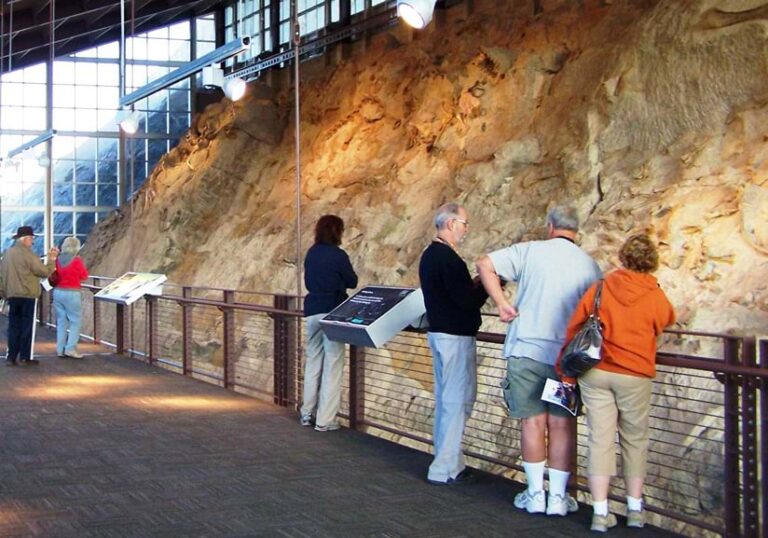

Waterfalls, geysers, sprawling canyons, and snow-capped mountains are the natural treasures typically associated with US national parks. Mostly unseen are the prehistoric relics—the fossils. They indicate where and how ancient life lumbered, burrowed, swam, slithered, and thrived millions of years ago.

It’s only through fossil discovery and preservation that people know about prehistoric butterflies frozen in volcanic ash in Colorado, North America’s oldest human footprint in the sands of New Mexico, a herd of more than 200 ancient horses in Idaho, or entire petrified forests in Wyoming.

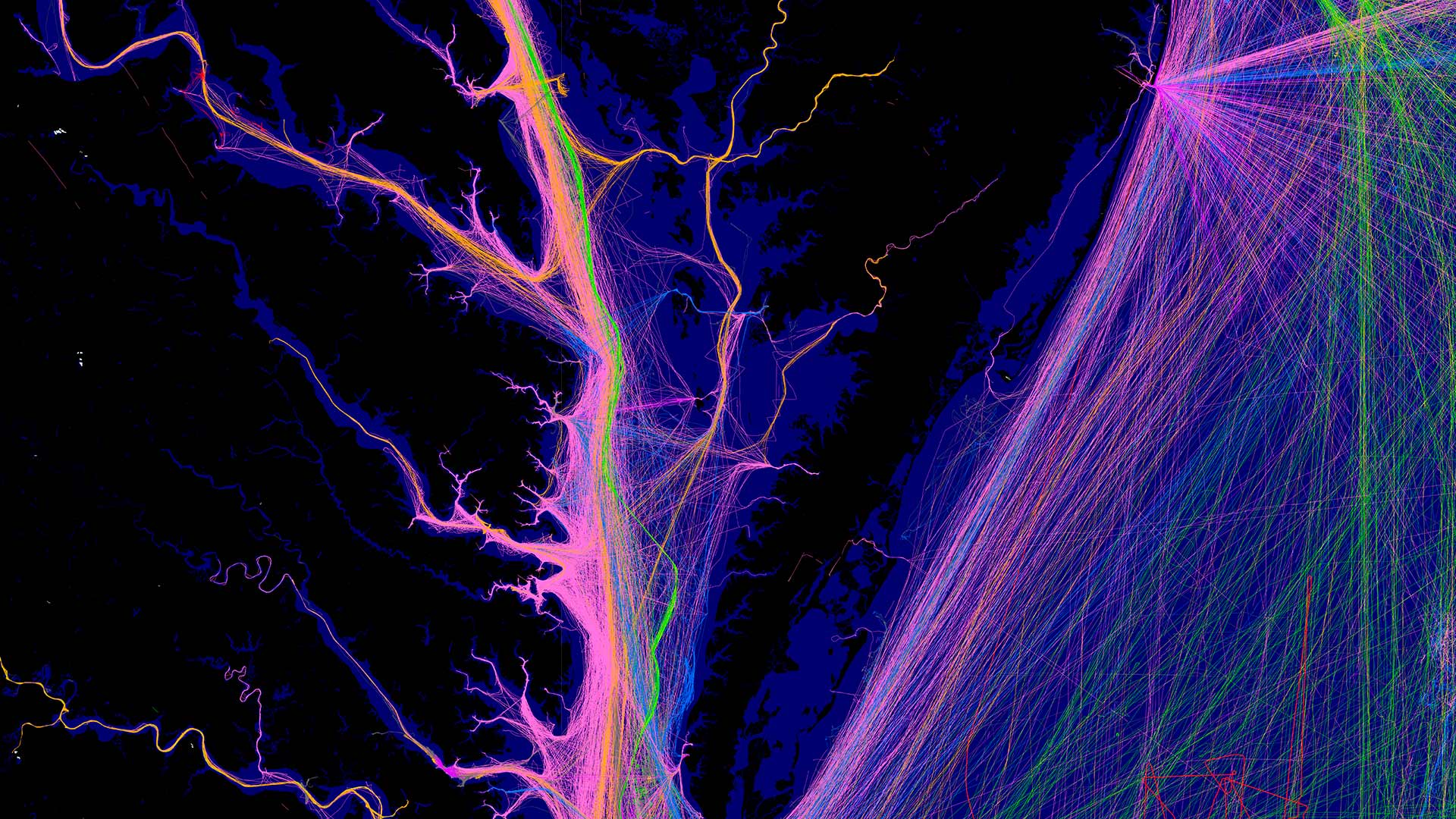

National Park Service (NPS) staff don’t just do conservation and education work—they also manage and protect fossils found in national parks. In recent years, NPS has been standardizing how it tracks and documents these fossils using a range of GIS tools such as ArcGIS Dashboards and ArcGIS Experience Builder. ArcGIS Survey123 allows NPS staff to collect and record data about a found fossil and upload that data to a GIS database. This helps them preserve ancient treasures and share what they learn.

Before 2005, park staff relied on handwritten notes for fossil records. When new discoveries were made, they’d search through old paperwork, consult land surveys, and ask longtime employees about similar finds in the area. This manual approach often led to errors and duplicated work.

There had to be a better way. That was the thinking among park staff in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area as well as in the NPS Paleontology Program and the geographic resources division of the park system’s Intermountain Regional Office. Together, staff at these locations began developing a new standard for keeping track of fossils, one that would allow for better visualization of a park’s paleo resources, provide the ability to ask broad questions of the data, and help in making decisions about monitoring and managing those resources.

That’s when Amanda Charobee was hired as a GIS specialist for the Intermountain Regional Office. She worked closely with Glen Canyon to create a standardized solution for fossil data collection and collation that could be expanded to other parks in the region.

Bringing Efficiency to Paleontological Data Collection

The NPS paleontological team, based in Washington, DC, frequently works with individual parks when a need arises, especially in parks that don’t have paleontologists on staff. That need sometimes occurs when there’s a major construction project in the park, where erosion or changing lake water levels have increased, or when the park’s staff develop plans to inventory and monitor their paleo resources. While large fossil-rich parks have their own paleontologists, other parks partner with outside experts like state geological surveys to document discoveries.

To bring the needed uniformity to how fossil discoveries are documented, Charobee worked with fellow NPS GIS specialist Meghan Thompson to create a mobile app that any staff member can download to a phone or tablet. From this app, data collected about fossils syncs to a shared database.

ArcGIS Pro was used for the development of the geodatabase schema underpinning the data management system. Collected and updated data can be integrated into spatial data engines (SDEs) for individual parks. Although not all regions currently use SDEs, the overall data management project is structured to ensure that it can adapt and grow to fit different workflows.

To build the mobile app and database, Charobee worked with rangers and paleontologists to identify a total of 55 key data fields, including survey routes, search areas, fossil locations, specimen details, photos, and monitoring information. Thompson then took that foundational plan and created a more general standard for all parks in the region to follow.

“By adopting a uniform protocol, we have developed a cohesive framework that allows effective sharing and management of paleontological resources,” said Thompson.

At Glen Canyon, Charobee and Thompson faced a major challenge: The park has 770 different locations where fossils have been discovered since 1928, which meant having to organize a massive amount of data and details, including more than 2,500 photos.

So far, Thompson and the team developing the new data management system have worked with 34 parks in the eight states that make up NPS’s Intermountain Region, collating all existing paleontological data and uploading it to a secure shared site.

The web app for this project was built using ArcGIS Experience Builder, which hosts the project home page. It includes information regarding the project; its status; and links to individual dashboards for each park, created with ArcGIS Dashboards. Because of the sensitive nature of the compiled data, this site is secure and accessible only to authorized staff through curated groups.

The Intermountain Region includes Arches National Park, Bryce Canyon National Park, Colorado National Monument, Grand Canyon National Park, Petrified Forest National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Zion National Park—all of which are well-known for their paleontological findings. Of the region’s 87 parks, 74 have paleontological resources. Eventually, Thompson plans to connect with parks nationwide to collect and manage paleontological data. Standardizing data, formats, and technology, Thompson said, will strengthen fossil protection in parks and eventually make it possible to more easily identify imperiled fossil sites based on the locations of other fossil finds.

Keeping Fossils and Data Safe

Privacy, even within individual parks, has been a top priority for fossil information. Information about exactly where fossils reside is strictly guarded to prevent theft or damage. Fossils have official protection under the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act, passed in 2009.

“Fossil theft is a huge problem,” Charobee said, not only inside the national parks but around the world. The database is hosted on the park service’s secure server for sensitive GIS data, with each participating park assured that its data will remain viewable to only those who need access.

To learn from a fossil, it is essential to know exactly where it was found. Once removed from its original location by a collector or tourist, a fossil loses valuable clues into how the animal may have behaved when it was alive and what the environment was like, Charobee said.

For instance, workers at Glen Canyon, which spans parts of Arizona and Utah, recently found fossilized dinosaur feces. How exactly did the dinosaurs relieve themselves? Researchers had a better idea after observing well-preserved tracks near the fossilized waste (coprolites). Seeing how the tracks and coprolites were arranged led paleontologists to theorize that the dinosaur had crouched.

Now, those dinosaur footprints and fossilized feces are among the fossil resources recorded in the NPS paleontology program records. Ultimately, park staff can use the fossil collections and related data to not only provide immersive and interpretive experiences for national park visitors, but also improve awareness, resource management, and education.