Wildfires have emerged as one of the most common natural disasters, posing a significant threat to public safety nationwide. This holds particularly true for western US states, which have been grappling with unprecedented fire seasons on a seemingly endless loop. Over the last two decades, numerous communities have embraced Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs) to prepare for these incidents. These plans provide a comprehensive view of a community’s wildfire risk, pinpoint critical infrastructure, and offer vital information to help determine where impactful mitigation efforts can reduce risk across the landscape.

In a groundbreaking move, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allocated an unprecedented $1 billion to support the development of CWPPs and bring mitigation projects to life, promoting risk reduction. It’s a significant down payment that has the potential to change the wildfire landscape for the better. However, there’s a slight catch: The current approach to CWPPs hails from a time when technology was far from cutting-edge. Considering the obstacles faced by the fire service in communicating wildfire risk and mitigation strategies to the public, it is evident that modernizing CWPPs is imperative for their future effectiveness.

The Impacts of Wildfire on Human Health, Environments, and Ecosystems

Wildfires pose a significant threat to human health, life, and the built and natural environments. Today, more people than ever live in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where structures or other human development intermingle with vegetation. In fact, WUI is the single fastest-growing land-use type across the country, with one in three homes now located within WUI areas. When a fire occurs, the loss of homes, businesses, and other property can be catastrophic, leaving individuals displaced and communities to recover from devastation.

The impact on the environment can be just as devastating. While many ecosystems have evolved to depend on fire occurrence, when fires burn too hot and too severe large swathes of land can be destroyed, ruining habitat and natural resources.

Moreover, wildfires contribute to air pollution, releasing enormous amounts of carbon dioxide and other harmful emissions like fine particulate matter (PM2.5) into the atmosphere. These pollutants not only exacerbate climate change but also pose serious health risks to humans. In fact, a new study estimates that in the contiguous US, wildfire-related PM2.5 is annually responsible for 4,000 premature deaths with a corresponding economic loss of $36 billion.

The consequences of wildfires extend far beyond the immediate destruction. Damage can continue long after a fire has been extinguished and the cleanup process has ended. For instance, and at the risk of oversimplification, soil can become unstable after a wildfire has consumed vegetation—trees, shrubs, and other ground cover. Once the soil in these areas becomes unstable, it is more susceptible to erosion from wind and water. Thus, the long-term risk of landslides and debris flows dramatically increases. This long-term risk further underscores the critical need for effective wildfire prevention and mitigation.

The Importance of Accessibility and the Planning Process

CWPPs have traditionally been delivered as written documents, some with well over 200 or 300 pages of content. Plans can incorporate everything from meaningful fire spread models and evacuation routes to the science and methodology behind vegetation type and health identification. While these elements may be important to include, realistically many fire management employees and most members of the public never engage with these materials. At times, much of this information is hard for fire management professionals (myself included) to understand, let alone the layperson or a community.

The type of information mentioned above is essential. It should be a part of any CWPP, but one cannot deny the importance of accessibility and a team-oriented approach. Imagine the untapped potential of reformatting these plans into a user-friendly online format that contains a veritable treasure trove of information at the fingertips of curious community members. Anybody can peruse the plan from the comfort of their living room, engage with interactive risk maps, and explore fuel treatments and mitigation plans in 3D. This style of delivery helps to pique interests and may even turn people into fledgling wildfire aficionados.

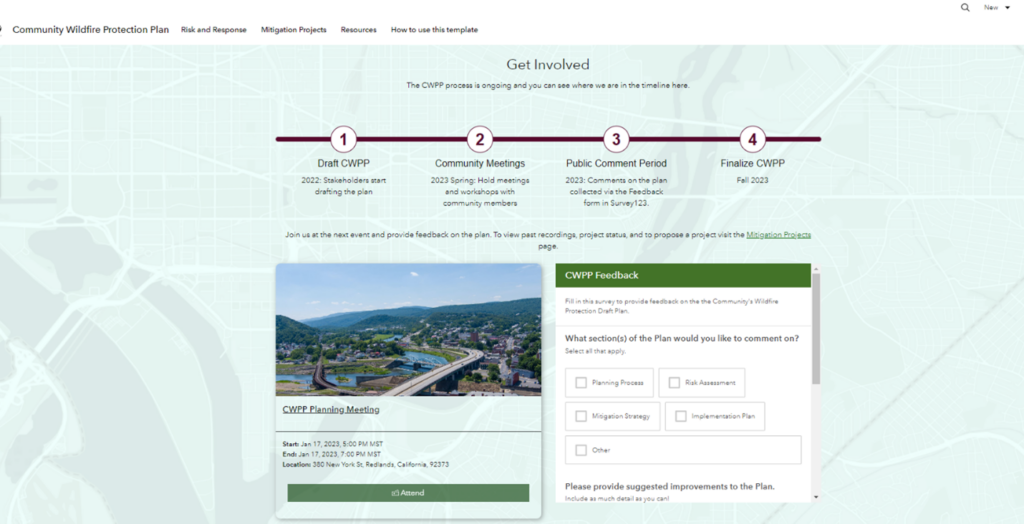

The digitization of CWPPs not only democratizes knowledge, but it also fosters a sense of camaraderie as community members engage in the planning process. Picture lively in-person or virtual meetings, with neighbors sipping coffee and engaging with fire departments, land management agencies, and other stakeholders. By shifting the focus of CWPPs from merely serving as a means to secure grants or as a collection of unengaging facts, and transforming them into a storytelling medium that highlights the community’s unique characteristics, we foster a sense of teamwork.

This approach transforms the CWPP into a cooperative and engaging instrument for wildfire planning and prevention and underscores the importance of the planning process itself. A successful CWPP goes beyond merely presenting facts—it unites communities and stakeholders in the shared pursuit of risk identification and reduction. As observed by US president Dwight D. Eisenhower (paraphrased here), plans are useless, but planning is everything. In that spirit, we find inspiration for a more connected and effective CWPP.

A Changing Landscape

Over the past 20 years, the frequency and severity of wildfires have changed in ways that have lengthened a fire season to a fire year and produced record-setting destruction seemingly with each passing year. For wildland firefighters, strategies and tactics have also evolved in light of the changing fire environment. It follows that it is overdue for community wildfire planning processes to catch up to the times.

To keep pace with the expanding WUI and ever-increasing wildfire risk, CWPPs need to be more accessible, engaging, and relevant to the communities for which we are planning. We need to transform the industry paradigm, shifting from traditional paper-based plans to dynamic digital alternatives that foster community engagement and streamline planning processes. To help foster this change, Esri has developed a CWPP template using ArcGIS Hub.

ArcGIS Hub and Why It’s Suited for CWPP Development

ArcGIS Hub is a cloud-based engagement software as a service (SaaS) that enables organizations to communicate more effectively with their communities. You can create a hub site using ArcGIS Hub to aggregate resources and start conversations with internal and public audiences around a specific project, topic, or goal. Think of your hub site as a geoenabled website!

The transition from paper to digital CWPPs offers numerous benefits, including increased accessibility, real-time data updates, and a more interactive experience for community members. ArcGIS Hub allows stakeholders to create, manage, and share digital plans with ease, enabling organizations and communities to stay connected and informed throughout the planning process.

One of the most significant advantages of using ArcGIS Hub to support CWPPs is its ability to foster community engagement. ArcGIS Hub provides an intuitive interface, encouraging participation from anyone from the layperson to the wildfire expert. Interactive maps, visuals, and other multimedia content make it easier for community members to understand the complexities of wildfire protection planning and contribute their insights and ideas. This collaborative approach ensures that the voices of all stakeholders are heard and incorporated into the final plan, ultimately leading to a more robust and effective strategy.

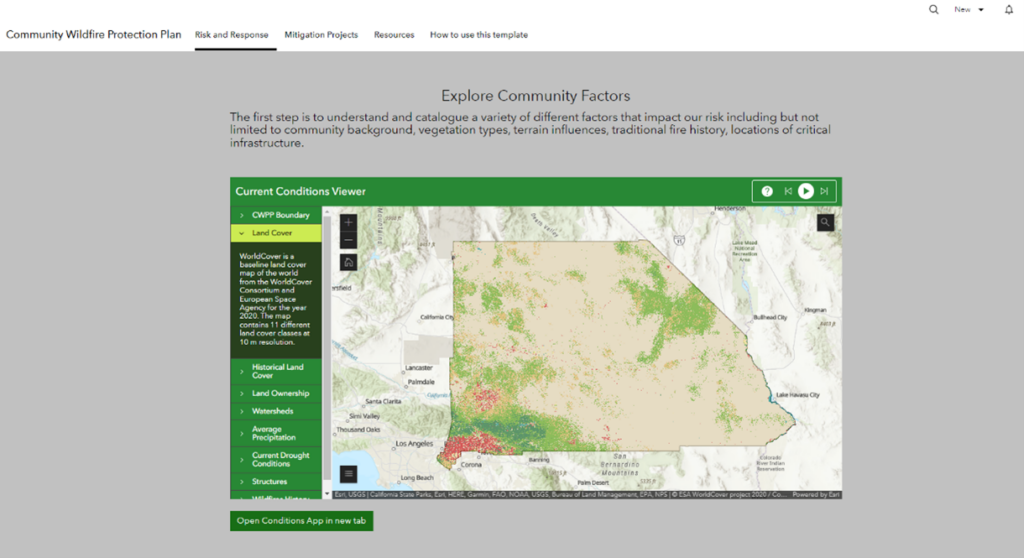

ArcGIS Hub simplifies and accelerates the planning process by providing tools for data collection, analysis, and visualization. Users can access and integrate a wide range of datasets, such as local land use, infrastructure, vegetation, and fire history, to create comprehensive and detailed CWPPs. ArcGIS Hub enables stakeholders to identify patterns, assess risks, and prioritize mitigation efforts with greater accuracy and efficiency. By helping streamline these tasks, a CWPP template in ArcGIS Hub frees up valuable time and resources that can be redirected toward implementing vital wildfire protection measures.

The value of communication and transparency in the CWPP process cannot be overstated. ArcGIS Hub promotes seamless communication and collaboration among stakeholders, including local government agencies, emergency responders, landowners, and community members. The sharing features in ArcGIS Hub make it easy to disseminate updates, solicit feedback, and coordinate efforts among all parties involved in the planning process. This level of transparency and information sharing fosters trust and cooperation, ultimately leading to more successful CWPP outcomes.

Conclusion

ArcGIS Hub is set to redefine how we approach community wildfire protection planning. By embracing digital transformation and harnessing the capabilities in ArcGIS Hub, we can create more accessible, engaging, and effective CWPPs that truly reflect the needs and concerns of our communities. We can leverage technology to build a safer, more resilient future in the face of growing wildfire risk.

To request a demo of the CWPP template for ArcGIS Hub, contact Anthony Schultz, director of wildland fire solutions, by emailing aschultz@esri.com.

Additional Resources

Community Wildfire Protection Plans – Guide for Deployment and Digitization