The cloud may feel intangible, but the infrastructure that powers it is anything but. Data centers have quickly become the backbone of modern digital life, and demand for them is accelerating. Economic Development Organizations (EDO) that used to pursue and recruit data centers now find the data centers reaching out to them. However, the process of siting these facilities is not just a technical exercise. This is a complex planning challenge that requires a meticulous, data-driven process, coordination across multiple disciplines, and ultimately, a geographic approach. For city and county planning directors, the rise of data centers introduces new pressures: reconciling zoning codes with modern infrastructure needs, balancing economic development goals with community concerns, and ensuring that essential public services can support these massive facilities.

Why Data Centers Strain Traditional Planning Processes

Unlike other industrial or commercial uses, data centers combine characteristics of both infrastructure and industry. They demand massive and redundant electrical power, significant cooling capacity (often tied to water use), strict security measures, and proximity to fiber optic networks. But they do not generate much foot traffic or conventional employment, which can make them a poor fit in some areas that are traditionally zoned for industrial or commercial activity.

This mismatch means planning directors often face a gap: existing zoning categories rarely anticipate facilities that are part warehouse, part utility, and part high-tech fortress. The result is a planning process that requires both flexibility and foresight.

The Many Dimensions of Siting Data Centers

A modern data center is not just a box with servers—it’s a hub of interconnected systems. At the heart of this challenge lies GIS. For planners, GIS is the most powerful tool for analyzing suitability, modeling impacts, and coordinating stakeholders. Without it, the multidimensional nature of siting a data center would be nearly impossible to manage.

Planning directors must consider how each of these dimensions intersects with the built environment:

- Public Works Infrastructure – Water and sewer capacity can be make-or-break issues. Cooling systems require steady and substantial water supplies. At the same time, stormwater management must be factored into site planning, as large facilities almost always introduce significant impervious surfaces. GIS allows planners to overlay existing infrastructure maps with proposed sites to identify capacity constraints.

- Electrical Utilities – Data centers are energy-intensive. Some facilities consume as much electricity as a mid-sized town. Planning directors must work closely with utilities to assess substation capacity, transmission line proximity, and redundancy requirements. GIS can model the spatial relationship between candidate sites and existing power infrastructure.

- Economic Development Organizations – From a jobs perspective, data centers don’t always deliver the workforce impact of a manufacturing facility. However, they can be major sources of tax revenue and attract ancillary businesses. Planners must weigh these trade-offs in partnership with economic development leaders.

- Public Safety & Security – Data centers often require enhanced security measures—perimeter fencing, controlled access, and sometimes police coordination. Their critical role in digital infrastructure also raises questions of resiliency and emergency response planning. As it does with thousands of communities, GIS provides a wealth of tools for public safety, from line of sight analysis, to incident management, to periodic security reviews.

- Transportation – While data centers don’t generate high levels of daily traffic, they do require reliable access for construction, maintenance crews, and emergency services, in addition to the workforce. Planners must evaluate roadway capacity and connectivity to ensure access without disrupting surrounding land uses. This should include access to transit, which may be particularly challenging given the remote nature of many data centers. GIS can help model potential traffic count increases and identify potential issues in regard to capacity and transit access.

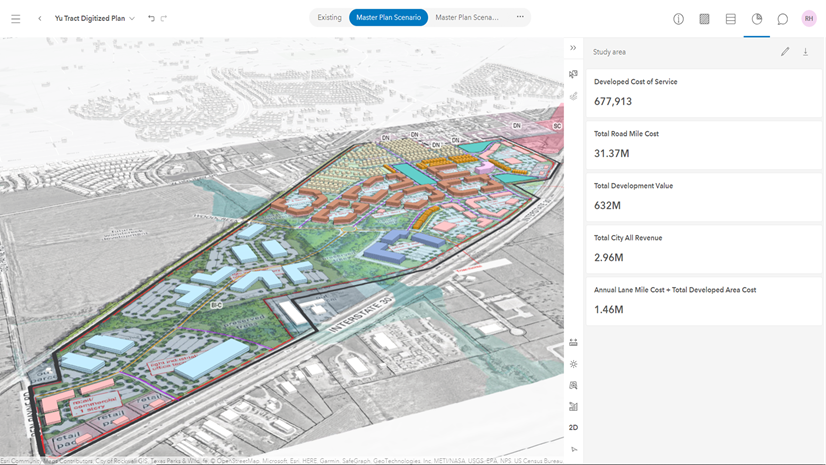

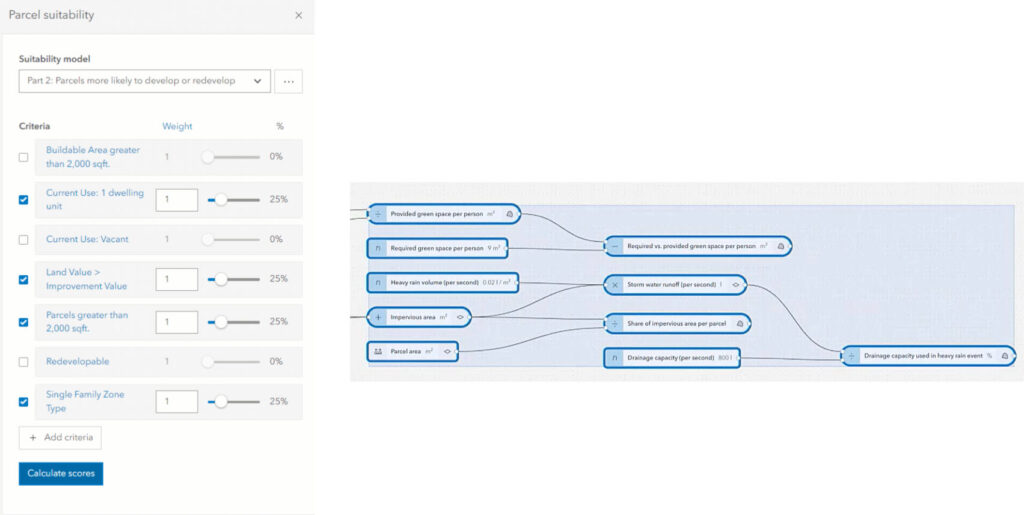

Performing parcel suitability analysis and modeling the impacts of impervious surfaces of a data center in ArcGIS Urban

Closing the Gaps in Zoning and Land Use

Over the last decade, the need for data centers has grown more than most communities could have predicted. Even the most modern zoning codes, let alone legacy codes, were not written with data centers in mind. Planners may find themselves shoehorning these facilities into categories like “light industrial” or “warehouse,” neither of which is an exact match. The result is ambiguity, which can complicate both approvals and community engagement.

Forward-looking communities are beginning to introduce specific land use definitions for data centers, recognizing their hybrid nature. Doing so allows planners to set clearer expectations around site design, buffering, height, noise, and utility requirements.

Where should data centers be permitted? The ideal sites balance infrastructure access with minimal conflict to surrounding uses. Industrial parks, utility corridors, and areas near substations or fiber backbones are common candidates. GIS analysis is again critical here by mapping zoning overlays, utility corridors, environmental constraints, and transportation networks to allow planners to zero in on the most suitable parcels.

Find the Perfect Site Using ArcGIS as a Planning System

The complexity of data center siting makes GIS indispensable. Since ArcGIS works as a planning system, it provides a common platform where multiple layers of information such as utilities, transportation, zoning, environmental data, and more can be analyzed together.

For example, ArcGIS can quickly identify parcels that:

- Fall within industrial zoning (or areas where rezoning may be viable).

- Reside within a defined buffer of high-voltage transmission lines.

- Have proximity to sufficient municipal water and sewer capacity.

- Avoid floodplains, severe slopes and other environmental constraints.

- Maintain reasonable access to arterial roads, and ideally, access to transit.

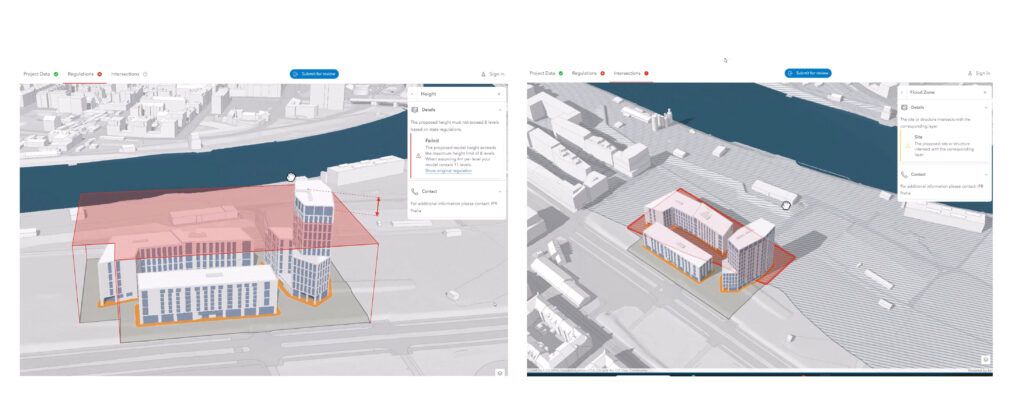

Beyond site selection, GIS also supports community engagement. Planners can use maps and 3D visualizations to communicate trade-offs, show why certain sites are viable, demonstrate how impacts will be mitigated, and even provide a realistic rendering of what the data center would look like. This transparency can help address community concerns and build trust and the buy-in necessary for a successful siting.

Performing site review of a potential data center. What looked like a prime location has flood zone and building height restrictions.

The Planning Director’s Balancing Act

Siting data centers is rarely straightforward, and the process does not exist in a silo. Planning directors must balance the technical demands of infrastructure with the broader goals of land use compatibility, economic development, and community well-being. The process demands not just regulatory oversight, but proactive vision, sometimes with multiple scenarios that anticipate where this growing sector fits within the urban and regional fabric.

As data demand continues to surge, planners who embrace GIS for data-driven, multi-disciplinary approaches will be best positioned to guide their communities. The cloud may be global, but data centers (and everything that goes with them) are local. How well they integrated into our communities will shape both digital and physical landscapes for decades to come.