Listen to Dr. Dawn Wright describe her trip to the Challenger Deep.

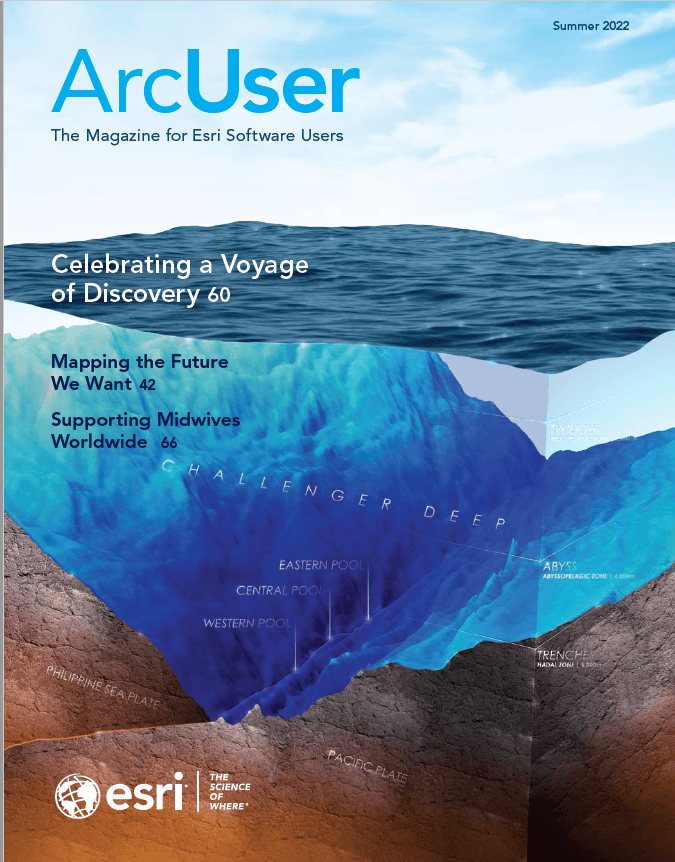

On July 12, 2022, Dr. Dawn Wright, an esteemed oceanographer and Esri’s chief scientist, made a historic voyage to the deepest known point in the Earth’s ocean. Victor Vescovo, undersea explorer and founder of the ocean research company Caladan Oceanic, piloted the submersible Limiting Factor, and Dawn served as the mission specialist. They descended nearly 11 kilometers (6.83 miles) to Challenger Deep, an area in the Mariana Trench near Guam.

There is much to celebrate about this historic journey. Only 22 people have visited Challenger Deep, a number that only recently exceeded the number of people who have walked on the moon. Dawn was the first person of African descent (of any gender) and the fifth woman to dive to the world’s deepest point. This mission was also the first successful side-scan sonar mapping operation at full ocean depth.

This trip provides a magnification of her life’s work. All of us at Esri could not be prouder of our Deep Sea Dawn and all she has accomplished during her career.

GIS Technology for the Ocean

Much of Dawn’s work has involved firsthand observation and analysis of undersea realms and phenomena whose power and beauty are almost indescribable. More than three decades ago, she was part of a contingent of scientists who descended to the East Pacific Rise, an underwater ridge where two tectonic plates are separating from each other. At that time, they came the closest to witnessing an historic volcanic eruption. Building on that experience, Dawn became a leading authority on marine geomorphology, the field that studies the geology of the ocean floor.

Early in her career, she realized the importance of mapping as a tool for both analysis and communication and became an early developer of GIS technology for the ocean. She cofounded the Ocean, Weather, and Climate Special Interest Group, which meets yearly at the Esri User Conference, and wrote two books for Esri Press.

It was her drive to improve GIS for use by scientists that led her to join Esri in 2011. She saw a gap between how GIS was developing and how it could be used to better accomplish scientific endeavors. Working with Esri developers, Dawn has helped the company improve its software to support the needs of all scientists, including oceanographers.

In particular, she was instrumental in helping to develop 3D capabilities and complex fluid systems modeling. Aided by her deep understanding of the crucial differences between ocean and terrestrial mapping, she worked to develop a method for depicting changes to these systems over time. As a company, Esri has always been committed to listening to its users, and Dawn has served as a conduit to address user needs in the scientific community.

The Need for Ocean Mapping

A decade after she joined Esri, the work that she and her ocean science colleagues are accomplishing around the world could not be more vital. Since the ocean covers nearly three-quarters of our planet, mapping the ocean has always been important. Precise ocean mapping is crucial for generating realistic maps of our world.

Today, however, ocean mapping has achieved a new level of urgency. Climate change, overfishing, and acidification jeopardize the health of entire marine ecosystems. Biodiversity loss and the destruction of coral reefs threaten the ability of the ocean to provide food for millions of people and the smooth functioning of the blue economy, which the World Bank defines as the sustainable use of marine resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of ecosystems.

Understanding the ocean’s dire predicament requires the kind of clarity only a rigorous, data-driven approach can provide. For a system as complex as the ocean, that means using the most advanced mapping techniques. Dawn’s championing of GIS—so important 30 years ago—is now nothing less than essential.

This has required a great deal of catching up. It is no exaggeration to say that we have maps of Mars and our moon that are more complete and detailed than our ocean maps. To date, only 23.4 percent of the ocean floor is mapped to modern standards. The Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project aims to fill in the map with high-resolution data by the end of the decade.

A complementary effort to develop a 3D map of our ocean’s ecosystems has been created through the efforts of Roger Sayre of US Geological Survey, Dawn, and her Esri colleagues. Through the partnership of Esri and the US Geological Survey and in collaboration with many other research and government organizations, the result was the ecological marine units (EMUs) and new methods of 3D marine mapping, which provided a baseline method for understanding the ocean’s ecosystems and established a framework for detecting change.

EMUs quantify ecological values of the ocean with statistical clustering of distinct ocean properties that most likely drive ecosystem responses such as salinity, dissolved oxygen, and temperature. With EMUs, conservation-minded organizations, academic institutions, or citizen scientists can gauge positive or negative trends and use data to make informed decisions that preserve marine environments.

Together, these efforts lay the groundwork for understanding, which in turn can drive policy. As we continue to map the ocean, we do not know exactly what we will find, which underlines the need to pursue the task wherever it might lead.

Tools that Will Aid Discoveries

Dawn’s trip to Challenger Deep was a particularly stark example of the ocean’s mysteries, but it is also a powerful symbol that we have the tools to map those mysteries to the benefit of humanity. Dawn and Victor brought with them a type of advanced side-scan sonar that had never been tried at such great depths. Hopefully—once the data is processed in the coming weeks—it will yield more detailed maps of this final frontier.

No matter what this data reveals, we will have Dawn’s powerful first-person account of the voyage. And I’m sure it will further reinforce her sense of wonder, which she will share to motivate all ocean mappers. A fascination for the unknown will serve us well in the challenging years ahead.

Saving the ocean will require global cooperation. Maps that drive that effort must develop in an open way that fosters collaboration. Although there was only room for two in the submersible that transported Dawn and Victor, the world traveled with them.

Additional Resources to Explore

- Enjoy the stories about Caladan Oceanic’s 2021 expeditions with this ArcGIS StoryMaps collection.

- Read about all the ways GIS is used in marine science.

- Get a behind-the-scenes look at the expedition of Challenger Deep.