ArcGIS Pro is a toolbox, and inside this toolbox is an almost limitless set of tools. Just as a carpenter’s tools are designed to work with and manipulate wood, the material we work with in ArcGIS Pro is data. We can alter the appearance of data using symbology, visibility ranges, definition queries, labeling, masking, and other operations. We can alter data itself using geoprocessing and editing tools.

Because we can do so much with and to data as GIS users, one common mistake we make is to throw all the data we can find into a map. I have done this as many times as anyone. That’s when the first thing I do is find and download as much data as I possibly can when I start a project.

At that point, I step back and wonder, what am I making?

It would be as if a carpenter went to the hardware store and bought a bunch of mismatching fasteners, wood that had been cut to random lengths, and some glue.

Instead, the carpenter first needs to answer the following questions:

- What is being made?

- Who is it being made for?

- Why is it being made?

- How will it be made?

Focusing Our GIS Projects

To focus our GIS projects most effectively, I argue that we need to rough out a project before we start to work on it. We need to identify what we want to make, who we are making it for, how we do and do not want it to be used, and any constraints on how our product works. We can focus our GIS efforts using these five project considerations: vision, budget, scope, time, and audience.

Vision

When making something, a carpenter may have all the tools but needs an idea and should be able to answer these three questions in a single sentence:

- What do I want to make?

- What can I do with it?

- Why do I want to make it?

For example, an answer might be, I want to make a table so that I can eat a family meal more comfortably.

As GIS users, we can apply the same questions to rough out GIS projects. Answers might be, “I want to make a web map that shows car crashes so I can design safer streets,” or, “I want to make a database that stores parcel information for my organization to use,” or, “I want a printed map of potential locations to open a new business.”

When we answer these questions concretely, we narrow the number of tools we need for the project. We reduce the number of potential products we will make. We simplify the search for data.

Budget

In a perfect world, we could make whatever we wanted, whenever we wanted it, and cost would be no object. In this world, our projects and products face constraints—budgetary constraints being chief among them.

And if we put nonfinancial resources under the umbrella of budget, we can also start to picture the technical, infrastructural, or staffing constraints on a project as well. To understand project constraints, we need to answer the following questions:

- Do we need to buy things such as server space, new computers, software, add-ins, or licenses?

- Do we have adequate staffing to create and maintain the project?

- Do we need to provide training on new technologies or workflows?

- Can we afford to do all these things?

- Alternatively, can we only afford to do some of these things?

If someone asks a carpenter to build a table, two of the first questions the carpenter will ask are What kind of table do you want? and How much are you willing to spend? In other words, the carpenter is asking, What is your vision? and What is your budget?

Scope

To put it simply, scope defines the stuff we care about and the stuff we don’t care about. In defining the scope of a project, we start to identify how we can achieve our vision within constraints.

For example, once a vision and a budget are set, the carpenter and the customer will start to define how large the table should be, how it should look, what kind of wood should be used, and other details. Within that scope, the carpenter can meet the customer’s expectations and find opportunities to add specific embellishments to the table.

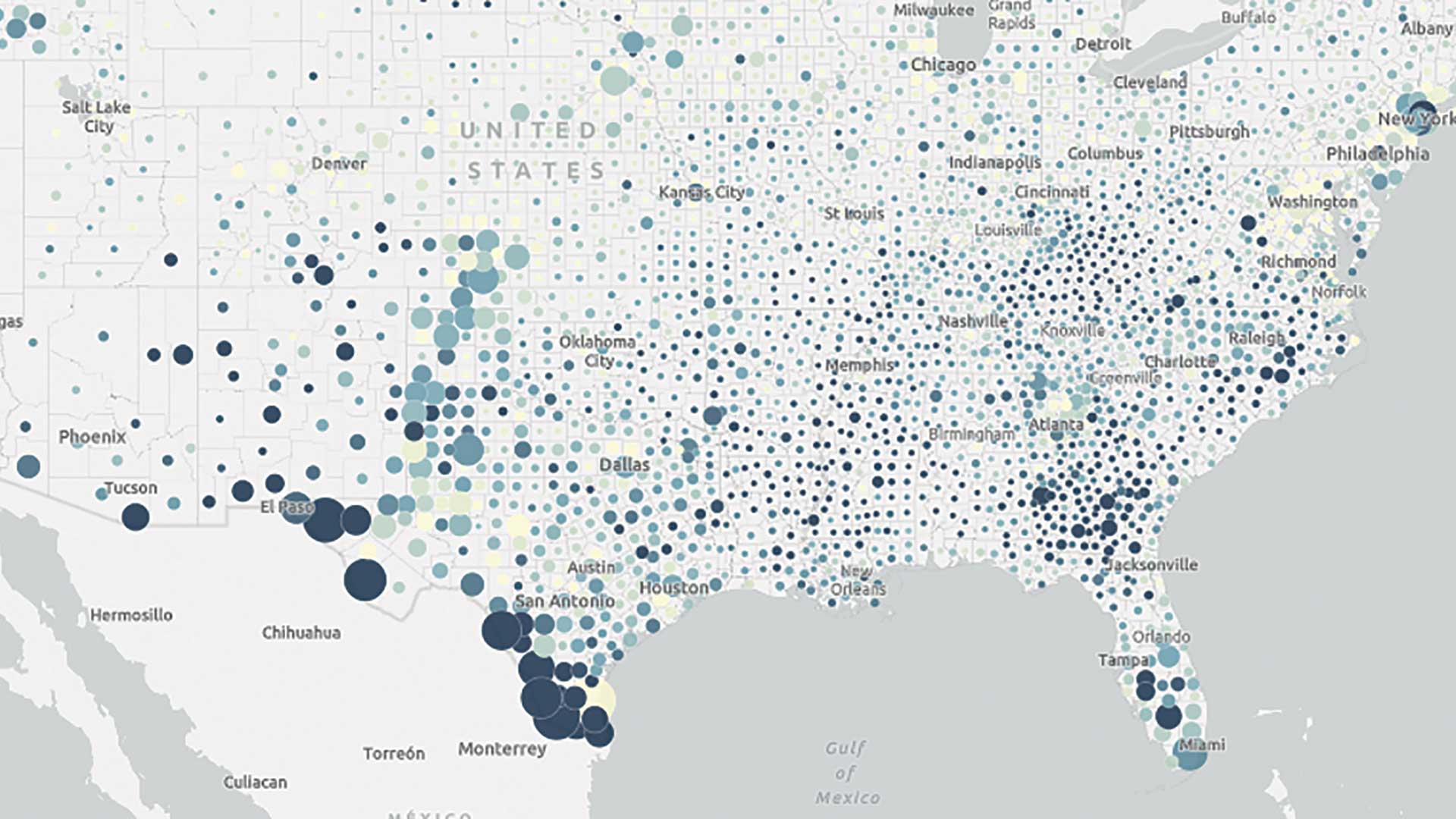

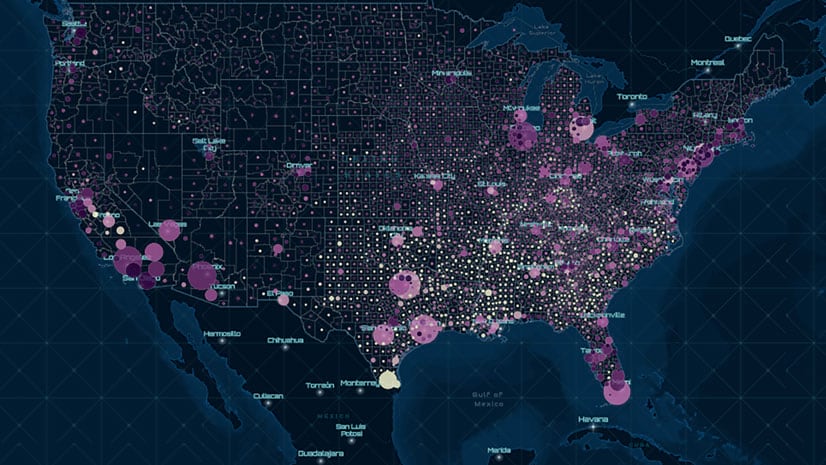

In GIS, we can narrow down the set of materials we work with when we define a geographic area of interest, identify data providers we want to use, and outline the workflows or processes we will use to realize our vision. From there, we can create beautiful maps, apps, dashboards, hubs, and other information products. We are not here to investigate everything, because doing that often gets in the way of the one thing we want to make.

Time

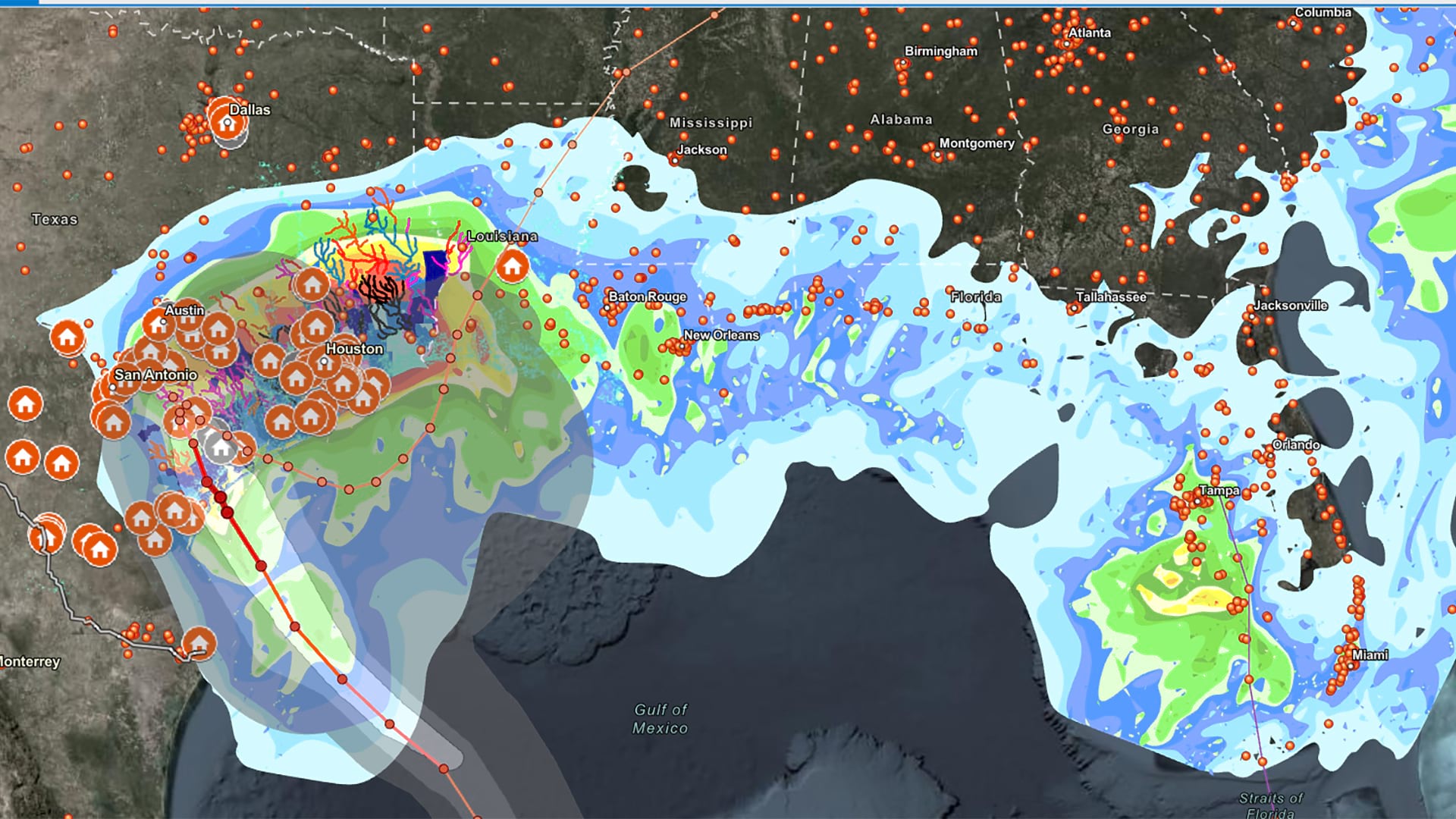

When do you need your table?, the carpenter might ask the customer. Deadlines are probably top of mind when you think of time in relation to a project. We live in a fast-paced world in which information is constantly updated, so delayed project deliveries might mean making decisions with imperfect or outdated information. But beyond deadlines, work in GIS also involves what I would call the temporality of a project: the relationship of our project to time.

On one hand, incorporating temporal components in a project adds considerable depth and richness for product end users. On the other, temporality adds an immense amount of complexity for GIS users and organizations.

Let us use a simple, concrete example. We just came to an agreement about the vision, budget, and scope of a new project we want to initiate. We want to create a public web map of population density in New York City. We can only afford to use public data available from the US Census Bureau. We want to make this information available as soon as possible. To accomplish this goal, we could use ArcGIS Pro or ArcGIS Online to access decennial census data. If a population density field does not exist, we will have to add and calculate a field to generate the necessary attributes. Then we can symbolize and share our data.

But if we want to know how population density in New York City has changed since 2000, we must ask and answer all kinds of additional questions because space and data that describes it change over time, too. Census boundaries change. Data definitions and categories change.

We will likely need to expand the scope of our project in such cases. Not only will we need to perform extra processes and workflows to our data, but we will have to spend more time understanding the variegated terrain of the data.

Common temporal questions we might ask of our project include

- How did data categories, definitions, and boundaries change?

- What processes or workflows will we use to resolve temporal differences in our data (e.g., apportionment)?

- When working with economic data, how do we adjust for inflation?

- Does it make sense to generalize data or resample rasters to make temporal comparisons easier?

Audience

Unlike the carpenter, whose audience is self-selected and specific, we often create GIS products with an amorphous understanding of audience. We tend to think of an intended audience or a group of people we think would be interested in our product.

Sometimes the audience is the public, a small group of stakeholders, or subject matter experts. Sometimes the audience is composed of members within our organization. Each potential audience has different ways of interacting with the products we create. Each has a different level of familiarity with maps and GIS concepts such as spatial statistics or raster analysis. To identify the audience for your GIS project, answer the following questions:

- Who is the audience?

- How will they use this product?

- What story will this product help us tell?

Considering our intended audience will help us decide how much specificity or level of detail we must incorporate into our project; select the kinds of technologies through which to make our product available; and determine accessibility requirements, symbology, design details, narratives, and other considerations.

I encourage you to document and record your project considerations before you go out and download every dataset you can find. That way, you can assess whether an unforeseen spatial relationship or a specialized web app meets your overarching vision. Although it will take more time up front, you can save yourself a lot of headaches down the line.

On the other hand, if you make these considerations too rigid, you may not be able to meet expectations, and you cannot pick the project up from an earlier moment. You get stuck and waste resources.

To get unstuck, I suggest using these project considerations as guideposts. Check in with yourself or your team regularly. Make sure your vision still makes sense. Make sure the scope is still correct. Make sure you can create what you want for the audience who needs to see it.