The Salton Sea, located in the Imperial Valley of Southern California, is both an important wildlife area and an endangered ecosystem. The State of California has embarked on a decade-long program to save this area. The program’s progress is monitored using GIS.

Accidentally formed in 1905 when an irrigation canal carrying water from the Colorado River breached its banks while under construction, the Salton Sea became California’s largest lake. Water flowed unabated into the Salton Sink for more than 18 months before engineers were able to stem the flow. The result: the Salton Sea.

Although irrigation runoff from the Imperial and Coachella valleys and local rivers collects in the Salton Sea, its location 225 feet below sea level means that water does not flow out of it. The increasing concentration of salts has caused salinity that is now 50 percent greater than that of the ocean.

Despite its degradation, the Audubon Society considers the Salton Sea to be one of the most important nesting, wintering, and stopover sites for millions of birds in the western United States. It has been designated an Audubon Important Bird Area (IBA) of global significance that more than 400 species of birds regularly use. However, BirdLife International, the world’s largest partnership for nature conservation, has designated the Salton Sea an “IBA in Danger,” indicating that the habitat area is at severe risk.

The State of California is responding to the urgent need to revitalize the Salton Sea before it suffers irreparable damage. The Salton Sea Management Program (SSMP) is a 10-year program that includes funding and oversight for rehabilitating a portion of the Salton Sea by developing aquatic habitat and reducing exposed lake bed.

The $206.5 million Species Conservation Habitat (SCH) project, a part of SSMP, will cover exposed lake bed in the southern region of the Salton Sea, build berms, and create habitat that supports fish and provides resting and nesting areas for birds. The project will also mitigate significant health hazards from dust produced by the dry lake bed that contributes to the poor air quality for people living in the region.

The state contracted with Kiewit Infrastructure West Co., which began the project construction in 2021. Kiewit hired LSA, a California-based environmental consulting firm, to conduct biological monitoring to comply with environmental regulatory requirements and permit conditions. The incorporation of GIS has streamlined all biological monitoring processes for the project.

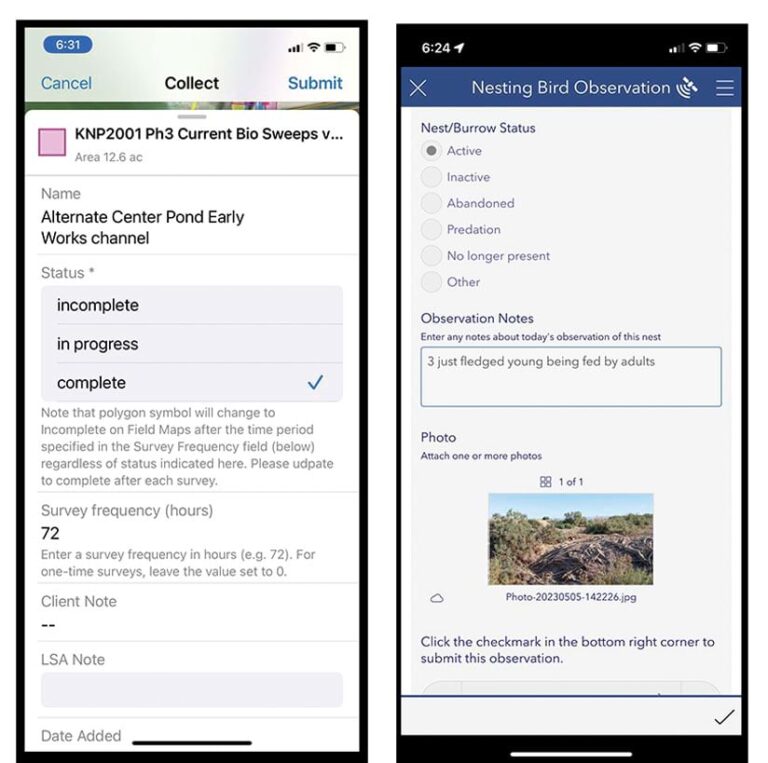

“Our biologists record detailed observations about nest location, status, and activity,” said Holly Torpey, senior GIS specialist/developer at LSA. “In addition, they report on the presence of adults, eggs, chicks, fledglings, and bird mortality. We monitor both resident and migratory nesting birds and record observations of any special-status species spotted within the site.”

In addition to its use by Kiewit for construction activities for permit and regulatory compliance, LSA biologists submit the data they collect to state and federal agencies involved in environmental monitoring. The firm also facilitates access to the site for the Audubon Society and Point Blue Conservation Science, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization, so that they can conduct migratory bird counts at the Salton Sea for the Pacific Flyway. The flyway is a north-south migratory route that extends from Alaska to Patagonia.

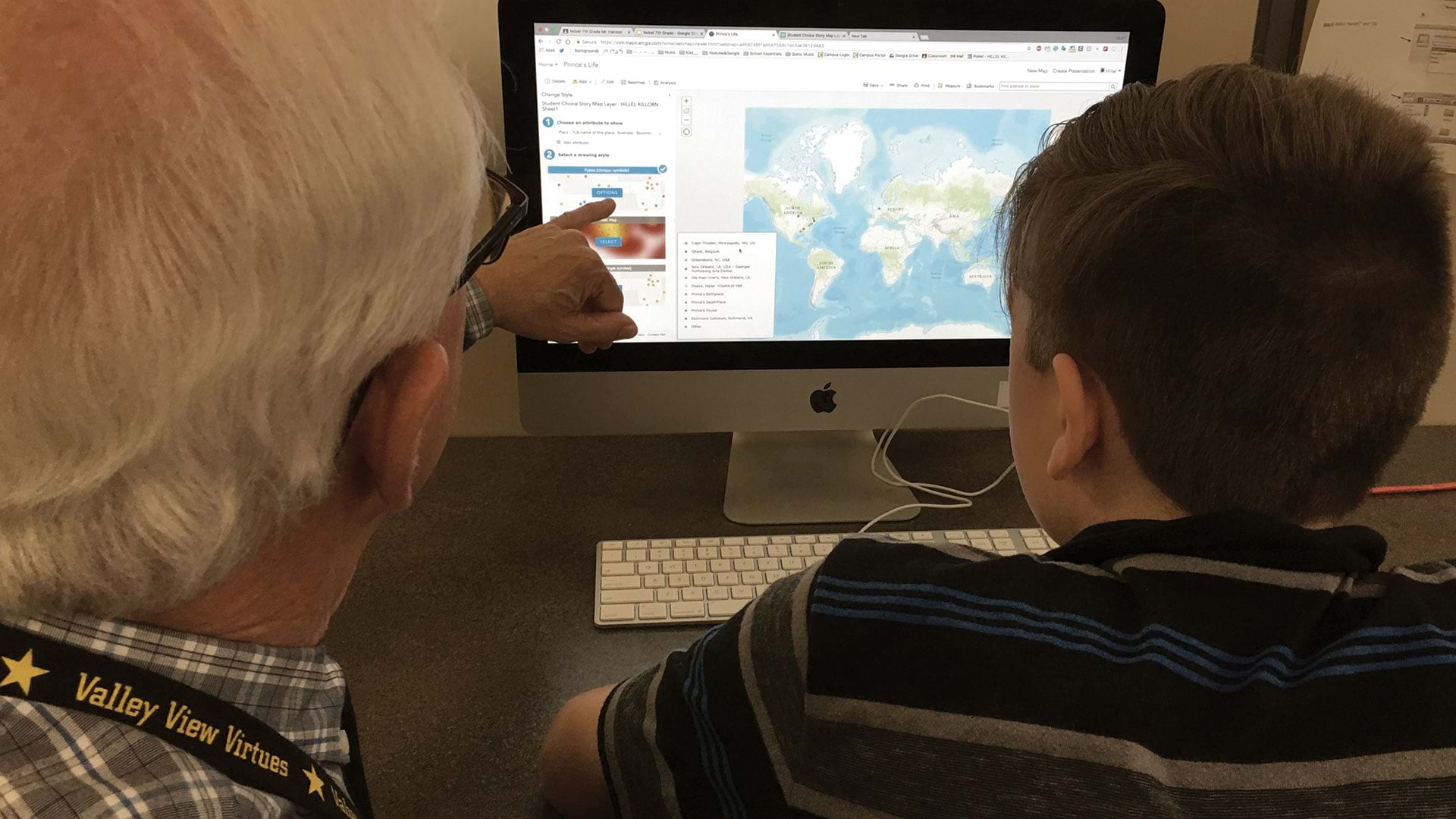

“The initial challenge in this project was to configure a data collection template for the biologists that enabled repeated observations of the same location without creating a new point each time,” said Torpey. “This was achieved through the use of repeats and related tables in [ArcGIS] Survey123.”

Another challenge was communicating with a large crew at a large, remote site. The location has limited internet access, and real-time communication among field crews, clients, and the project manager was sometimes spotty.

“We overcame the connectivity concerns by configuring both Survey123 and [ArcGIS] Field Maps to work offline and sync when an internet connection became available,” said Torpey. “To address communication issues, we developed dashboards and web applications to share field data with the lead biologist and project manager. The dashboard capabilities also allow them to monitor change over time and filter and extract requested data for reports.

“Kiewit and our project manager use the ArcGIS Instant Apps Sidebar to communicate priorities to our field biologists. They draw new nesting bird survey area boundaries and update their status each week,” said Torpey.

Survey area boundaries, displayed on biologists’ mobile devices in Field Maps and symbolized by priority status, let biologists know which areas they need to visit each day. The construction field engineer and the biologists can add notes to each area to communicate important instructions and observations.

ArcGIS Pro is used to perform spatial analysis, generate cartographic products for reports, and maintain field data collection templates. Kiewit supplies data on construction progress in CAD format, which is converted to geodatabase feature classes in ArcGIS Pro. Drone imagery and vector data are published to ArcGIS Online using ArcGIS Pro.

“GIS empowered our team to improve communication, workflow, and safety in a complex project environment,” concluded Christina Van Oosten, a senior biologist at LSA. “In addition to saving time and thus money, it helps keep the project in compliance with environmental regulatory requirements and permit conditions, which ultimately protects the sensitive natural resources at the site. The flexibility of the GIS applications gave us an opportunity to adjust and adapt as conditions and project needs changed. This flexibility is especially important to support the best management practices needed at restoration and habitat improvement projects.”