It was called the Great Flood of 2019 for good reason. During the wettest spring on record in the United States, multiple storms hit. Rivers overflowed, flooding the Midwest, the High Plains, and the South from January through June and impacting 14 million people. This flood was one for the record books across many areas of science. New records for high-water marks were set in 42 different locations along the Mississippi River.

Students at Western Illinois University (WIU) at the Macomb campus had a front-row seat. Macomb is located between the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers, north of where they meet.

“The Mississippi River was having extreme flooding, and the Illinois River just couldn’t drain,” said Chad Sperry, director of the GIS Center at WIU and a member of the state incident management team. Sperry was dispatched by the Illinois Emergency Management Agency (IEMA) to the State Unified Area Command (SUAC) in Winchester. He brought a team of GIS students to create maps that could help first responders from IEMA, the National Guard, Illinois Department of Transportation, Illinois State Police, US Army Corps of Engineers, and other agencies.

“There were a lot of road closures, so the students were involved in making detour route maps and other mapping products,” Sperry said. “We used drones to provide a real-time situational awareness capability. We were working 14-hour days for 16 days straight. The duration and the intense months of coping with flood response were exhausting.”

While flooding is a regular occurrence in many of the small communities along these rivers, it doesn’t occur to the extent and duration of these flooding events. Beardstown, Illinois, experienced 176 days of minor and moderate flooding. In nearby Havana, major flooding stretched for 37 days.

Providing a View of an Important Levee

In the unincorporated community of Nutwood, Illinois, Sperry and his team monitored the main stem levee system a few miles away from town.

“Nutwood isn’t significant in terms of population, but [it’s] very significant in terms of impact,” Sperry said. “It sits right at the bluff, so it’s almost out of the floodplain, but not quite.” Predictive modeling done by the US Army Corps of Engineers and the National Weather Service using GIS indicated this levee was going to fail.

The townspeople had built their own backup levee using bulldozers to push dirt from the farm fields around town. Unfortunately, the main levee failed, and then the town levee failed. When the Nutwood Levee was overtopped, it forced the closure of Illinois State Route 16 at the Joe Page Bridge near Hardin. It took weeks for the waters to recede.

Sperry and his team were there over the course of the levee failure, mapping Nutwood using drones and ArcGIS Drone2Map before, during, and after the levee breach. Detailed drone mapping and elevation models were used by IEMA to inform evacuation plans.

The team also used ArcGIS Survey123 and ArcGIS Collector for postflood damage assessments. Instead of using the paper-based system, the team photographed everything and collected data on Apple iPads. Sperry helped train everyone and kept them on task, even when that required guiding people through the uncomfortable process of adopting new workflows.

Keeping Rural Communities Mobile

Mapping transportation routes was one of the more critical elements of the students’ work. Floods closed many roads and bridges, and people needed to evacuate.

“The Department of Transportation had an expert traffic flow modeler that was optimizing evacuation routes,” Sperry said. “We imported that information into geodatabases to take it to the next step, creating map products to provide the context of where all the people would ultimately end up.”

Because many rivers lack bridges, ferries are used to cross the rivers. Road and bridge closures from the flooding made mobility even worse. Commuters to Saint Louis used their own boats to cross the river, choosing to park their cars across the river to avoid a three-hour detour around the flooding.

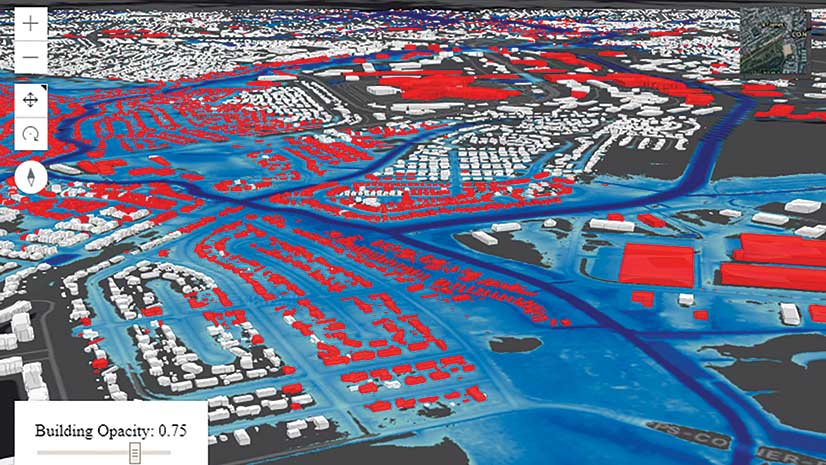

As the high water moved downriver, the team did some inundation modeling to help understand impacts as flooding neared Saint Louis. The team asked what would happen if a particular levee broke. They created flood extent maps to understand the effects. Incident commanders and planning section chiefs studied the flood extent maps to create contingency plans. By looking at potential outcomes, they could determine which homes and roads would be impacted and prioritize evacuation areas should the levees fail.

“We used something like one million sandbags during the event,” Sperry said. “Levees are typically built with an earthen core with sand over the top of them. Over time, the sand and core get saturated, and that puts pressure and stress on the surrounding soils. We had boils popping up a half mile inside the levee where the river found a path, and the team would put sandbags around those to equalize them with the height of the river.” [Sand boils occur when water under pressure wells up through a sand bed, contributing to liquefaction and levee failure.]

The US Army Corps of Engineers used ArcGIS Collector to mark and monitor the boils, any depressions in the levee, and anything out of the ordinary. That data about weak spots will be used to inform future levee improvements.

One View for the Team of Teams

The real-time data collected by different agencies and GIS students was fed into ArcGIS Dashboards and shared across the state.

“We built a dashboard with the National Guard to show where sandbag troops were being deployed,” Sperry said. After the first briefing during which the dashboard was used, the team moved into the main building, and the dashboard stayed up on the main screen.

Soon the dashboard was shared with the Emergency Operations Center in Springfield, and the National Weather Service in Chicago used it to see what was really going on from a levee status standpoint. It was used to brief the governor, department heads, state senators, and US senators.

Eventually, the dashboard aggregated and consolidated data from 10 to 15 GIS analysts working for various agencies. WIU students worked alongside experts. Pam Brooks, GIS specialist at IEMA, had already fostered relationships with GIS people from other agencies and was able to help coordinate the collaboration.

At daily morning briefings, the teams discussed any status changes on the dashboard. For instance, the representatives from the US Army Corps of Engineers would inform the group of any levee breaching or overtopping, or levees in a state of caution.

The students kept track of details such as shelter locations because sometimes shelters would have to move if a levee failed. Keeping that information up-to-date was crucial to making sure evacuees had somewhere to go.

“We would get requests to add something, such as weather overlays for radar, and the students would research and find the best live data to add to the dashboard,” Sperry said. “There were many hands-on opportunities.”

Lifelong Lessons Learned

The students gained a tremendous learning experience from these events, with immersion in the use of a wide variety of GIS tools and the need to deliver answers quickly during a crisis.

“We got a call one night, just as we were getting ready to go home for the evening, that a levee had just overtopped,” Sperry said. “So everybody just set their bags down and dug back in again. We were there for a couple more hours that evening.”

The flood events gave students crucial practice in the fast-paced, high-stakes world of emergency response using GIS—a common and important application of the technology.

“It was definitely the most stressful work environment I’ve ever had to work in,” said Ian Stearns, a WIU student majoring in meteorology who helped out. “Being able to learn how to control the stress of all the things going on, all the decisions you have to make, has been really helpful for me.”

When he joined the student team, Stearns had taken one GIS class and had worked at the GIS Center for three months in a paid position that gives students real-world experience.

“When we flew over the temporary levee in Nutwood to identify places it might fail, that was really fascinating,” Stearns said. “The way we were able to create a detailed digital elevation model from the imagery—and Chad Sperry was able to model water height in relation to it and other buildings—was awesome. I had never even thought of that kind of application of GIS.”

In between events, the students talked about GIS jobs and got to know emergency personnel. The students’ real-time skills made an impression on the GIS professional working on the efforts.

“One of our grad students had two different job offers from the US Army Corps of Engineers before he even got home,” Sperry said.

Although the Great Flood of 2019 set many new records—it was longer in duration and had higher floodwaters—Sperry said the damages were less than had been anticipated.

“We had eyes in the sky and the ability to predict and not just react. Instead of waking up to find that a levee broke in the night, we deployed sandbagging efforts to where GIS predicted it would break. We knew what was coming with the rainfall models and the gauge models. And so technology was really given a lot of credit for minimizing the impacts.”