With help from powerful location analytics and a revealing set of business data, two researchers have shed light on the connection between businesses and crime in a study that upends some stereotypes while validating long-standing claims of business owners.

Tom Y. Chang, an assistant professor of finance and business economics at the University of Southern California, and Mireille Jacobson, associate professor at the Paul Merage School of Business at University of California, Irvine, recently detailed their experiment in the Harvard Business Review article, “Research: When a Retail Store Closes, Crime Increases Around It.”

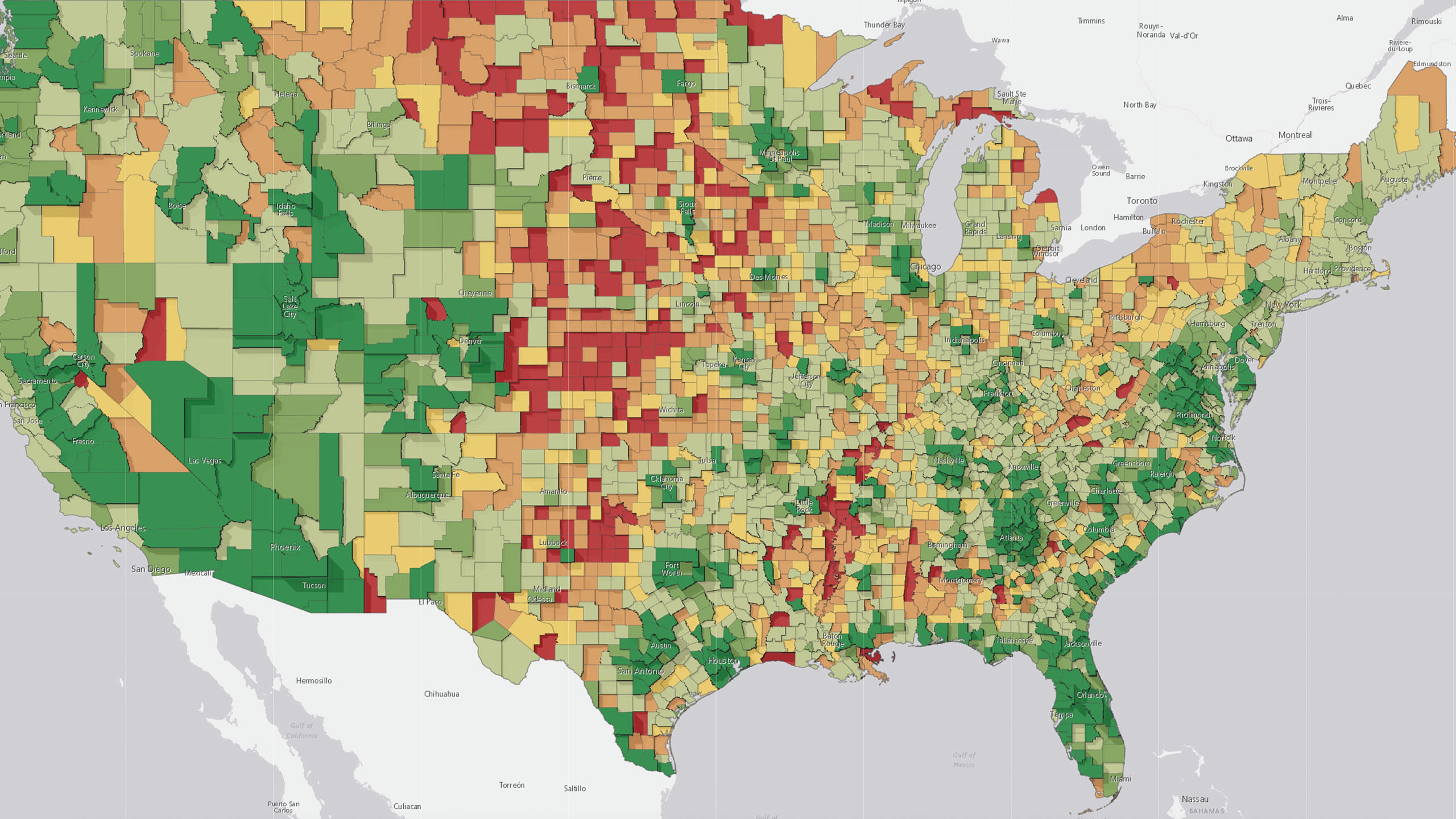

As cities and suburbs across the US embrace mixed-use development—communities where residents and businesses live side by side—the researchers set out to map real estate and crime data to examine whether some businesses contribute positively or negatively to the nearby crime rate. Capitalizing on publicly available data on Los Angeles, the pair first examined the closures of medical marijuana dispensaries. Opponents of the dispensaries have often stereotyped them as magnets for criminals.

The researchers found otherwise:

Surprisingly, we discovered that the closures were associated with a significant increase in crime in the blocks immediately surrounding a closed dispensary, compared with the blocks around dispensaries allowed to remain open.

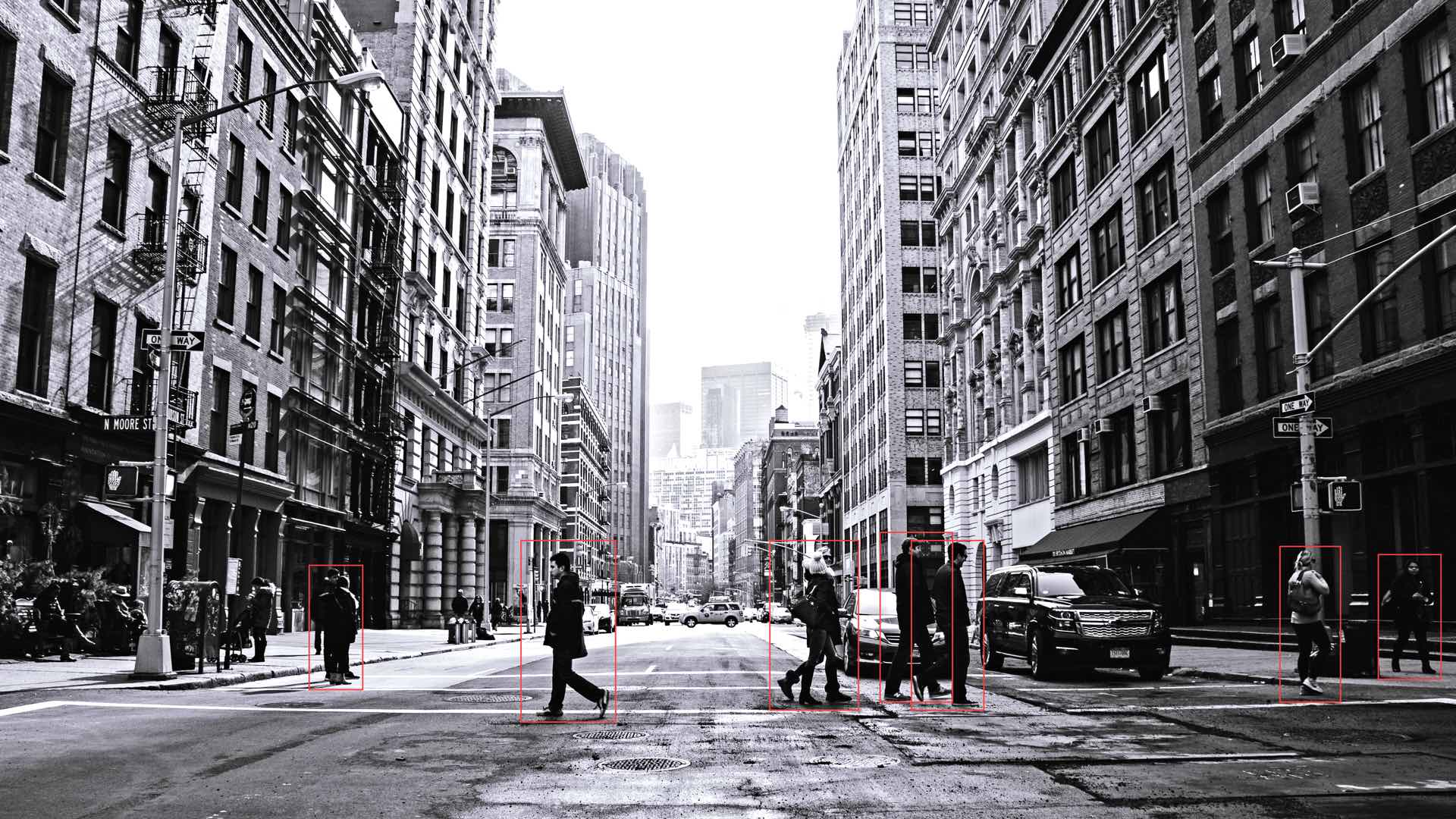

The researchers then analyzed the types of crime that occurred, and found that incidents following closures involved crimes most likely to be discouraged by foot traffic: property crime and theft from vehicles.

Next, Chang and Jacobson mapped Los Angeles area restaurant closures to see how they correlated to law-breaking. Plotting the two datasets on a map enabled the researchers to see if crime had increased in areas where eateries were shuttered.

The pair used a geographic information system (GIS) to conduct the analysis, Jacobson told WhereNext. “This allowed us to analyze the relationship between closures and crime in the area around the dispensaries [and] restaurants,” she explained in an email.

In the HBR article, she and Chang described what the GIS technology helped them see:

The area immediately around a closed restaurant experienced an increase in property crime and theft from vehicles, relative to areas around restaurants that were either recently reopened or about to be closed. Furthermore, this increase in crime disappeared as soon as the restaurant reopened.

The study helps counter a general stereotype about urban environments—that the more people you pack into an area, the more crime will arise. Some related stereotypes have lingered for decades. Nearly twenty years ago, the Boston Consulting Group issued a report titled, “The Business Case for Pursuing Retail Opportunities in the Inner City.” In it, researchers wrote: “The perceived magnitude of crime in inner cities may be exaggerated, partly because of excessive and perhaps myopic coverage by the media of criminal activity in those areas.”

A more recent study put a finer point on the misconception, with Time magazine noting:

According to a new study published today in the Annals of Emergency Medicine, large cities in the US are significantly safer than rural areas.

Walking the Beat

The USC and UC Irvine researchers further tested the connection between business and lawlessness by mining data on area walkability—determined by the number of nearby restaurants, coffee shops, grocery stores, and other features that generate foot traffic. They then combined that data with Los Angeles crime statistics. Like most data drawn from the civic realm, foot traffic can be mapped to illustrate the patterns associated with it.

Chang and Jacobson found that consistent foot traffic in an area thwarts crime—another refutation of the idea that crime comes with crowds. By contrast, commercially dead areas showed more property theft incidents, suggesting that crime flourishes in urban areas where there are fewer patrons to witness and report it.

As for the economic implications, the article states:

A quick, back-of-the-envelope cost calculation using our results and crime costs from a 2010 study suggests that an open retail business provides over $30,000 a year in social benefit just in terms of larcenies prevented… It’s something urban planners should keep in mind as well when zoning neighborhoods. Retail businesses draw customers, and in doing so, lower crime.

By enlisting public data on business closures and crime statistics and then visualizing their relationship through GIS technology, Chang and Jacobson applied location analysis to a persistent question about businesses and community health and dispelled some myths in the process.

To learn more about location analytics and smart city planning, listen to the recent podcast, “Building a Data-Smart City,” featuring Harvard University Professor and former Deputy Mayor of New York City Stephen Goldsmith.