Have you ever had to share your latest project, and you weren’t quite sure how to make it interesting to your audience? Sure, in your world you may be really into sea turtles, or tree species in a local park, or maybe an urban planning project. You hope your hard work will be interesting to the audience, but you could use some help. So, what’s the best way to capture their attention?

The answer: Try engaging them with a story.

If you’re intimidated by storytelling, or you’re not sure where to start, you’ve come to the right place. Let’s start with a definition, so we’re on the same page. Dictionary.com defines the word as:

sto·ry | [stawr-ee, stohr-ee] | a narrative, either true or fictitious, in prose or verse, designed to interest, amuse, or instruct the hearer or reader; tale

By the end of this post, you’ll know the basics of good storytelling, recognize its value in sharing your work, and begin to understand how to apply storytelling techniques to reach your audience.

Why tell stories?

This question has many answers, but for the sake of brevity, we’ll explore just three of them.

First, humans have evolved to be receptive to a story. It’s even indicated by neuroscience. Back in the early days of human history, elders told stories to teach survival skills. They shared how to navigate through the world, what things or places were dangerous, what foods were safe to eat, and who we could trust.

Why did we use stories for this? It has to do with neurons and oxytocin, and some really interesting science, but we’ll skip those details. However, the gist of it is that we’re more likely to remember a good story than a plainly recited and abstract fact without context. Stories are containers. They’re an effective tool helping our brains to process, store, and understand relationships between information. And remembering which path was safe to travel and which one is dangerous is important, so storytelling has always been essential for survival.

The human factor

This brings us to reason number two: Stories build connections between people. Just as we need to know which places are safe or not, we need to know who we can and can’t trust. Stories foster empathy, trust, and collaboration between people. Stories can also explain the relationships and context of events happened and help answer the question “How did we get here?”

Humans also understand that stories follow predictable structures. They’re set in a place. Most focus on a main character and include an event or a conflict, some activity that leads to a climax, and finally, closing the loop on the action. Professional projects often mirror this structure and have an existing framework you can use to build a story.

Think about your favorite movies. No matter the genre, they likely had a character facing a challenging situation. And, if the movie was any good, you were engaged with the events unfolding before you. Maybe great acting performances grabbed your attention. But a bigger reason you care is probably related to the narrative — the writer’s goal is often for you to see part of yourself in the film’s protagonist. In turn, you care about their wellbeing and success. Similarly, everyone faces relatable challenges in their own work — even if the details are different.

Challenge Accepted

The story Challenge accepted relates the journey of Esri’s Dawn Wright to the deepest point in the world’s oceans. Obviously, not many people have the personal experience to match, but in telling this story with Dawn as a prism — establishing the meaning and importance of the effort to Dawn and providing an in-depth look at the dive based on her own account — she becomes a protagonist that readers can relate to.

A third reason to tell stories: It can be fun! When told with intent, a story can be just as fun and rewarding for the person doing the telling as it is for the audience, and a storyteller’s enthusiasm can be infectious. This holds true even when the topic is more serious or niche. Many professional challenges involve conflicts or disagreements, and sharing your insights about those obstacles through storytelling can help further engage your audience.

In short, people are hardwired to engage with a well-planned and developed story, and telling a story can be just as rewarding as hearing, reading, or watching it.

What’s in a good story?

Another question with myriad answers, and we’ll address three major ones again.

Establishing setting

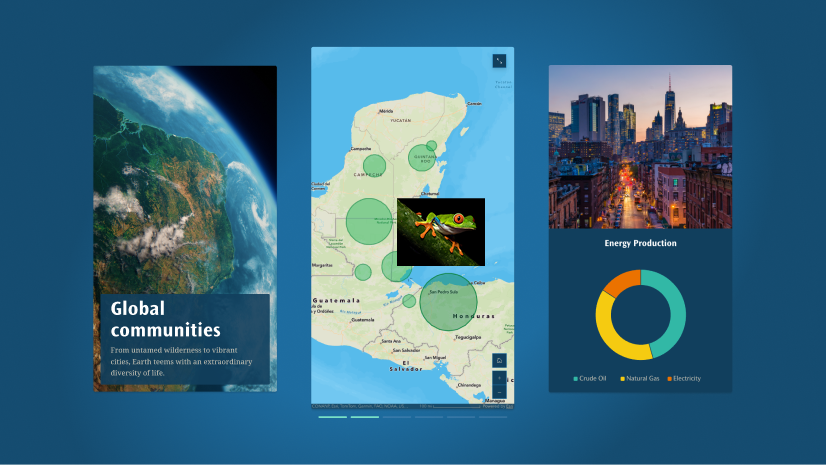

One thing that creates a captivating story is, an established setting — every story happens somewhere, after all. The more real that place feels to your audience, the more engaging it will be. Sharing details engages the senses — the sights, sounds, and other details can make a particular place come to life. The setting may even be a place in your community or one that’s relatable to your audience, and making the setting relatable, or at least imaginable, helps engage an audience.

When rains fell in winter

The story When rains fell in winter chronicles a rare weather event in Northwest Russia that dramatically impacted the livelihoods of reindeer herders in the region. The writers of the story use descriptive language, photographs, and maps to paint a vivid picture of the stark landscape in that part of the world. In doing so, they set up a clear understanding of how the catastrophic rainfall was able to affect the area in the way that it did.

Interesting characters

A second thing is all good stories feature established characters. We touched on this earlier, and it might seem obvious, but it’s worth going over. Remember thinking about your favorite movies? They’re often effective because the character development leading up the climactic scenes made you care whether, say, the villains catch the hero, or the couple ends up together.

So, how do you get someone to care about the cast in your narrative? Again, make them relatable. Describe their motivations, desires, fears — the details or situations an audience member can recognize in themselves or empathize with. When the audience connects to the character’s outcomes, then they’re hooked.

Dramatic effect

Once the character development leading up to the story’s climax inspires your audience to care about your character(s), then you can establish a third aspect of a good story: Tension. Essentially, tension is the gap between what is happening currently and what could happen in the future. Creating this gap usually starts with a conflict or problem introduced in the beginning, which leads an audience to want to know about the outcome. Will the characters meet the goal they set out to accomplish?

There is practically an unlimited number of ways to work these three elements — setting, characters, and tension — into a story. How you choose to do so will depend on variables such as the intended audience and the overall structure and flow of the story.

Answering the call

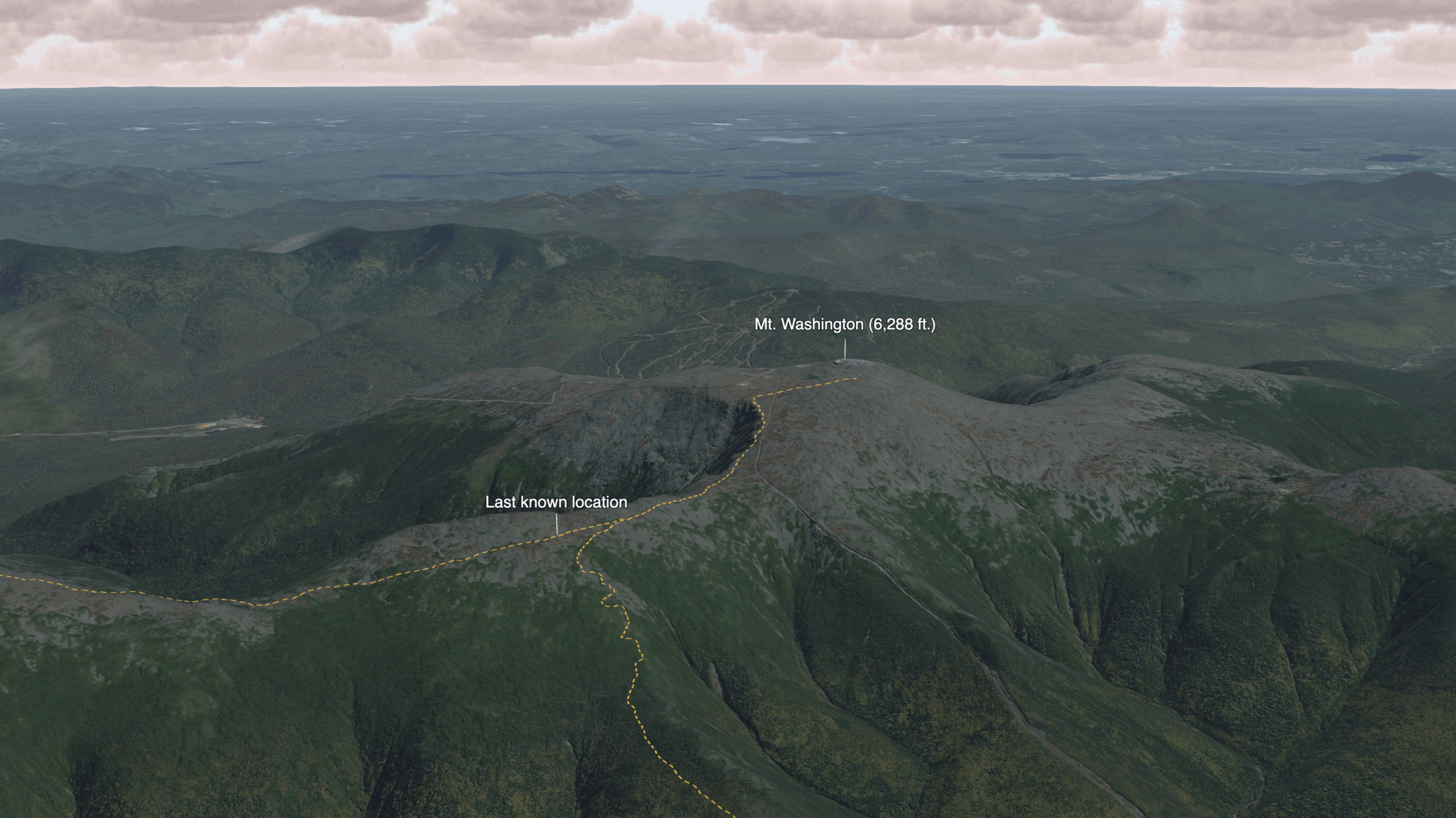

The story Answering the call, for instance, about mountain search and rescue operations, opens with a fictional vignette of hikers getting lost in the rugged wilderness as a storm approaches. This establishes, in vivid detail, the environment and climate and the threat they pose to unprepared hikers. Anyone who has ever gone for a walk in the woods before can see themselves in the boots of the hypothetical hikers.

Then the story introduces its characters — the men and women who comprise search and rescue units — before returning to a harrowing real-life account of an effort to find a missing hiker. The establishing of the setting in the introduction explained the stakes involved in getting lost, while meeting the rescuers themselves and learning about their process makes you invested in their success in finding the real hiker. Combined, those two factors provide a great deal of tension as the rescue attempt unfolds across a three-dimensional map scene.

How do you get started?

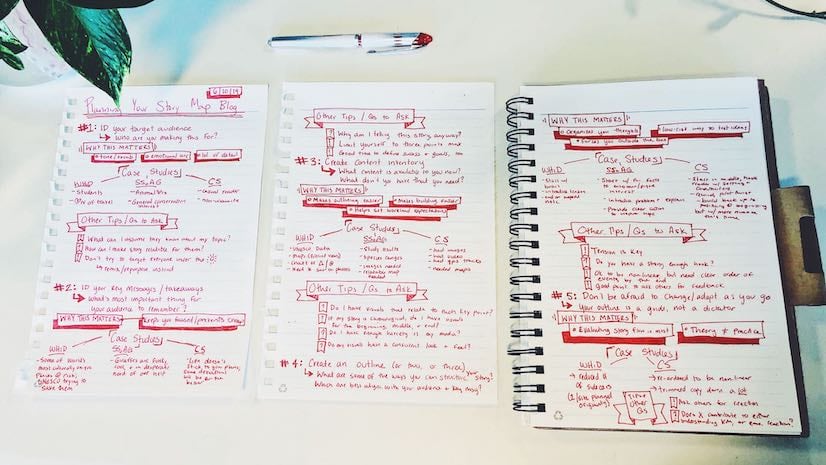

This is the best question and the simplest to answer. Creating a story where the audience has to know how it turns out does require a bit of thought. The first step is identifying your intentions: What do you want to say, to who, and why? Knowing your objectives helps you focus on relatable elements and minimize distractions. Remember to include human emotions — there’s likely to be challenges in most professional projects.

Next, make a high-level plan for your narrative arc. While you could just start writing a stream of consciousness, taking the time to outline first will pay off in the long run. It will help you get all the ideas out of your head, so you can think more clearly about each one. Then you can experiment with their ordering, seeing how different arrangements do or don’t create tension. A great way to do this is with sticky notes or index cards, but a bulleted list in your favorite note-taking app works just as well.

The most important step, hands down, is to just give it a try. Like all creative endeavors, no one starts out an expert. It’s practicing the craft that makes you better at it. You might love your story at first, or you might not — but give yourself permission to play and enjoy the process. Focus on having fun and saying what you need to say, and the rest of the skills will come with time. If you need help, check out some of our resources.

Everyone has a story to tell, and we can’t wait to see yours!

We would like to acknowledge this blog was adapted from an article written by our former StoryMaps colleague, Hannah Wilber.

Photo for When Rains Fell in Winter by Andrei Golovnev.

Article Discussion: