GIS and the Seismic Shift in Grocery Retail

In June, the grocery/consumer packaged goods (CPG) world was rocked by the General Mills announcement of their quarterly results. Sales were down 3 percent and net earnings were down a shocking 47 percent.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how differently we shop now, and this announcement confirmed some of the thoughts that have been running through my head. I’ve been involved in retail and grocery for more than four decades. As a practitioner, I’ve managed the planograms and worked with brands to position products, launch new concepts, and run promotions in one of the largest general merchandise stores on the planet. And not only have I been a practitioner—you can’t be in this business as long as I have and not also loving being in the store. I am a shopper, too.

Granted, I’m not the typical shopper. My industry experience means that when I walk through a store, I notice things that most people don’t see or care about. I see how items are placed on shelves, I see the packaging, I check out the shelf labels, I look at adjacencies and positioning. Like every retail “lifer,” it’s a side effect of thousands of store tours, walk-throughs, product sets, and line reviews.

I’ve spent a lifetime in stores but what about online shopping? I’m also an enthusiastic member (sometimes evangelist) of Walmart+ and Amazon, they all have my address programmed into their daily routes.

My retail background and personal experiences in stores and when shopping online has made me a keen observer of how these little interactions that drive consumer (or just this consumer’s) “black box.” I try to understand how these triggers work to influence consumer behavior at the lowest level. (Black box is the term retailers use to describe the synapses and intricacies of the consumer’s mind that cause them to grab one item over another when they’re staring at a retail shelf.) What triggers and incentives go off in my head that make me put an item in my physical or digital cart? And what is at play in the virtual world that makes the whole process seem reversed?

Online, I search for items; I don’t wander aisles. I see the price first, then I start to weigh my options. At the shelf, I tend to see the item first, the package design, and the product information before I see the price.

Which brings me back to General Mills. They posted a rough quarter—net income down nearly 50 percent is significant. That said, I’m not ready to jump on the inflation blame wagon. I don’t think this is just about inflation. In my mind, there’s a deeper issue at play.

Consumers have been shifting toward owned brands for a long time. Owned brands are the store brands that often resemble and even sit right next to the national ones on a planogram shelf. They look similar, but typically they cost less. And the images often look just as good on a website thumbnail. In a world where packaging, shelf placement, and in-store impulse buying don’t mean what they used to, the ground is shifting beneath traditional brands.

That shift, by the way, isn’t accidental. Retailers, for the most part, are on board. Owned brands come with better margins, more control, and tighter loyalty loops. If you love Bettergoods at Walmart, or Target’s competing Good & Gather products, you know you can’t get them anywhere else and, as a result, you become a loyal shopper. As product development has improved and quality has gotten better, the compromises these products used to represent are going away. Often, they’re the preferred item. Which raises the question: Are brands becoming the new showroom items? Still necessary, still trusted—but increasingly there to validate the aisle, not to drive the purchase?

These changes in how consumers interact with brands and assortments will require a focused and enhanced emphasis on assortment planning. When the emotional selling attributes of packaging and shelf placement are gone, and when the revenue generated by impulse purchases is gone, in grocery, all that’s left is intent. Retailers must figure out how to put relevant assortments in front of each and every customer. They need to understand during the planning stage what item goes where, why, and for whom.

And this is where geographic information system (GIS) technology comes in.

For years, retailers built clustered stores using CRM and POS data. Penetration analysis, sales reporting, and store-based reports were all useful and all relevant to managing product mix. The reality however is operational execution; store clusters were simply a workaround to scale localized merchandising strategies. They were a tool for retailers to execute planning and allocation when they didn’t have the ability or the data to execute assortments at the store level. Without store-level execution, there’s only so much localization and assortment rationalization that can be done. While intuitively, we were thinking about spatial analysis, we just didn’t know the about location technology that could enable the enterprise-level use of local store data. But now? There’s no reason to rely on gut instinct and often flawed “institutional knowledge” when making critical decisions about what customers will find when they scan a shelf or look at a page of items presented on their mobile device.

Location isn’t just an attribute—it’s a context.

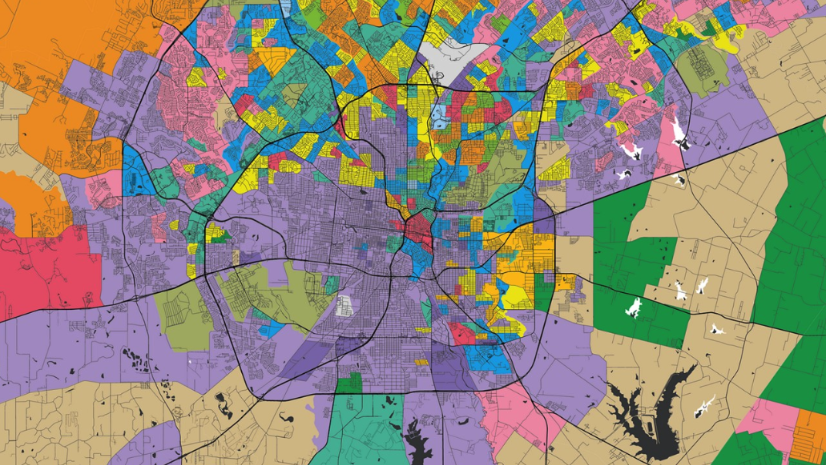

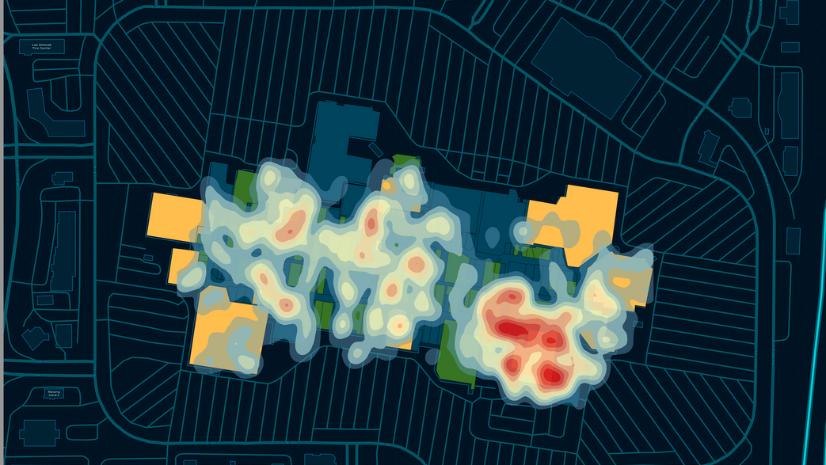

GIS allows retailers to bring in layers of data in a way that a CRM cannot: local demographics, temporal traffic data, nearby competition, and complementary retail; even regional dietary patterns and ethnic preferences are available. A GIS enables practitioners to expose the nuances in consumer behaviors and product performance. These localized insights can explain why two stores with similar shopper profiles sell radically different items. It allows retailers to zoom in to the customer point of view without losing the enterprise-level strategic view.

Trader Joe’s is often on my shopping trip. And it’s a good place to consider the outlier to my hypothesis while proving my point. There’s no e-commerce at Trader Joe’s, no online shopping or curbside pick-up or delivery. There are also no empty parking places in their lots. Trader Joe’s is thriving—and their customer loyalty scores are legendary. They can do this because they’ve doubled down on the one thing that digital has a difficult time replicating. The real differentiator at Trader Joe’s is serendipity. The treasure hunt. That “I wonder what I’ll find” feeling. To be sure, it’s reinforced with quality and great prices, but that’s not the first thing most people think of when they shop at Trader Joe’s. Think about Aldi for reference.

This strategy works brilliantly for Trader Joe’s. But it’s not scalable for almost any other retailer. Traditional grocery is built on brand partnerships, wide assortments, and customer expectations of consistency in stock, execution, and customer experience. Retailers just can’t walk away from that. Brands have a critical part to play. Brand managers offer deep expertise in their product lines. Their work in supply chain and planogram development offset expenses for the retailer. They fund promotions and they ensure a stable supply chain in their category. Most importantly, they lend credibility to the retailer and their offers.

Assortment Anchors

When I was at Target, I had a chance to visit Tesco stores in the UK. As I was walking the aisles of what on the surface looked like a nice but somewhat typical grocer, I found my way to the liquor aisle. I was quite surprised to see some very premium bottles of scotch on the planogram—bottles that retailed for over £150.00. I asked the buyer how many bottles of £150.00 scotch they sell in these stores. The response was, “One or two a year, maybe. But I sell thousands of bottles of cheap scotch because people see the good stuff, realize we are in the business, and then grab a more modestly priced bottle.” This example of assortment elasticity nicely sets up my next point on why brands are important: Brand managers can leverage their powerful data insights to help their retail partners drive business. So, when owned brands displace traditional brands fade? That’s not just a highlight on the margin line of a financial report; it’s a business model shift.

In this new world of retail assortment planning, GIS isn’t just helpful—it’s essential. It supports hyperlocal merchandising, smarter last-mile fulfillment, and spatial understanding of shopper journeys, both online and in store. It helps grocers plan more precisely and brands adapt more intelligently.

This moment where we find ourselves trying to react to seismic shifts in consumer buying patterns is a moment that demands strategies that reach beyond broad assumptions—strategies grounded in the most granular layers of consumer, product, and location data. That’s how you create tactics that will actually resonate, not just in theory, but in the store, in the aisle, at the shelf, and on the screens. The right offer, at the right time, in the right place. These variables come together at the right moment to drive sales.

Retailers need to have confidence that their enterprise-level decisions reflect the real conditions on the ground. And this is where GIS shines. Across industries, GIS has proven its ability to reveal why things happen where they do. In grocery, where traditional drivers of consumer behavior are shifting—and legacy marketing tactics are losing impact—that capability becomes indispensable.

Because when you understand the geography of demand, the context of the customer, and the complexity of the competitive landscape, you are moving past just understanding change, you are anticipating it. GIS empowers spatially aware retailers to connect the “where” to the “why”—and that’s the connection that will define who thrives in this next era of retail.