October 13, 2021 |

October 11, 2021

Maybe you’ve dreamed of catching a glimpse of the ivory-billed woodpecker in a southern swamp. Now the best you can do is watch a video, because in early October scientists at the US Fish and Wildlife Service declared this and 22 more species extinct. The cause of habitat degradation and destruction has raised fresh cries to set aside more land and ocean for nature.

Decades ago, Robert MacArthur and E.O. Wilson pioneered a theory to assess how larger conserved land areas support the survival of more species. Their original theory, developed in the 1960s, was born of research on island biogeography with the observation that larger islands contain more species, but it has since been applied more broadly to species preservation.

“The theory addresses biogeographical dynamics,” said Walter Jetz, professor and director of the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change. “Larger habitat fragments and those closest to other undisturbed forest habitats hold more species, and as humans encroach and create smaller patches that are less connected, you rapidly lose species diversity.”

Wilson articulated the theory in his 2016 book Half-Earth, Our Planet’s Fight for Life where he proposed, “Only by committing half of the planet’s surface to nature can we hope to save the immensity of life-forms that compose it.” In addition to reducing the human footprint, Wilson also called for a deeper understanding of ourselves and the rest of life on our planet.

The E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation’s Half-Earth Project, with Jetz as its scientific director, aims to tackle both of Wilson’s objectives. This global biodiversity conservation project has set out to quantify habitats and the geographic distribution of species—putting both on the shared open Half-Earth Project Map. The effort also looks at how land cover change and climate change affect habitats and their viability to support a variety of species. The goal is to support the right decisions and investments to curtail the current mass extinction.

“When you lose species, you lose important functions and services,” Jetz adds. “At some point, the key functioning—the intactness and integrity of the ecosystem—isn’t there anymore because too many species have been lost.”

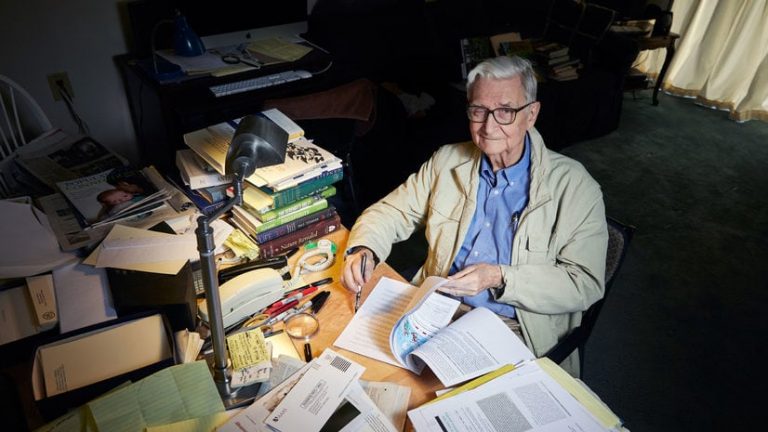

Wilson will soon join special guest Sir David Attenborough, along with Sir Tim Smit of the Eden Project at The Royal Geographical Society in London in a livestreamed global event for the fifth annual Half-Earth Day to take stock of the world’s progress.

As Wilson puts it in Half-Earth, “People understand and prefer goals. They need a victory, not just news that progress is being made. It is human nature to yearn for finality, something achieved by which their anxieties and fears are put to rest.”

There is perhaps nothing more troubling than losing a species forever, which is what has happened – again – with this month’s news from US wildlife officials. When we lose a species, there is often a disturbing ripple effect. Jetz, for example, points to the endangered oilbird in South America, the only nocturnal flying fruit-eating bird in the world. It serves as a major seed disperser in the forest, and if it were to be lost forever, we would likely see changes in forest structure.

Birds became Jetz’s obsession as a teenager and as an undergraduate student he started using geographic information system (GIS) technology to map and analyze their distribution. He went on to create the first global map of bird species during his graduate work.

“I’ve always been fascinated by maps, and then I got really fascinated by species and biodiversity and how environmental gradients change species composition,” Jetz said. “There’s a lot of information about birds and it’s a reasonably small species group with roughly 10,000 species globally. It was the first species where it was possible to grapple with issues of global biodiversity and the implications for conservation science.”

Since his early work in the 1990s, global maps of species distribution have expanded to mammals, amphibians, plants, invertebrates, and marine life. Putting this work into a shared map for collaborative science is now Jetz’s passion, to avoid duplication of effort and to pool efforts to arrive at a scientifically rigorous yet actionable knowledge base.

“Alexander von Humboldt was the first to draw some of these maps and gradients 250 years ago,” Jetz said. “Now it’s possible to take that into the quantitative scientific realm and to think not just about single species but to make the link to patterns of communities and the conservation relevance of places.”

Increasing volumes of data are helping underpin spatial decision-making to protect species at the local, regional, national, and global scale.

“We have the tools, and increasingly the science, to address this issue,” Jetz said. “We can take species into account, and we can include them in our planning and decision-making.”

The spatial dimension unlocks patterns of a species richness and rarity, including how their traits function across geography, how they relate to the history of an area, and where they are native and live in large numbers.

Determining the optimal area to preserve entails looking at hundreds and thousands of species in a region to identify priority places and think efficiently about safeguarding a maximum number of species in the least amount of area.

The project has created maps that weigh the importance of places, including metrics on human encroachment, existing conservation protections, and details about the species.

“It’s not simply the hot spots of richness that we need to conserve, but the right optimally designed network,” Jetz said. “In the Half-Earth Project science, we use the species distribution information to give each location a globally informed, quantitative priority score. It’s a dynamic map that changes as our knowledge progresses and our conservation progresses.”

The simplicity of the Half-Earth concept has helped it gain momentum, with core innovation in how to best care for our planet being guided by rigorous science. Both sides—conservation and quantification—have increasing urgency if we’re going to preserve biodiversity for future generations.

“The guiding mission of the Half-Earth Project is to leave no species knowingly behind,” Jetz said. “Extinctions will continue, but we shouldn’t be losing species unknowingly. We have a moral obligation, at a minimum, to be aware when we drive a species to extinction and to know how to safeguard every species.”

October 13, 2021 |

May 10, 2021 |

July 27, 2020 |