May 27, 2021 | Multiple Authors |

March 29, 2022

After drinking state-issued bottled water for months because of concerning lead levels, the nearly 10,000 residents of Benton Harbor, Michigan finally had a date for when they might be able to safely turn their taps on again: May 2023.

For those working behind the scenes to fix the problem, though, the new date meant doing in 18 months what would normally take as much as five years.

Abonmarche, the engineering firm for the small city, and a team of five contractors have been going house by house to determine if the water service lines running from the curb to a home’s meter are copper or lead. With incomplete records of the types of pipes that lie beneath, or where they are exactly, the engineering team turned to a geographic information system (GIS) solution. With GIS maps and apps, the contractors can collect data and coordinate the pipe inventory as they replace lead service lines across the city.

It’s work that will put them well ahead of an accelerated 2024 federal deadline for inventorying all the country’s water pipes to determine which are lead (and needing to be replaced) and which are not.

“If there are any issues, we can solve them here, now,” said Garrick Garcia, leading Abonmarche’s Benton Harbor GIS team.

Until recently, water providers have regularly monitored the level of lead in water, governed by standards that might trigger further action, like warnings to residents, bottled water distributions, and partial replacements of lead service lines.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is now mandating an inventory noting the material makeup of every single service line delivering drinking water by October 2024. EPA estimates put the number of lead service lines across the country anywhere from six to 10 million. Under the new rules, unknown materials are assumed to be lead, too. Beyond inventories, President Biden has also called for the full removal and replacement of all lead service lines in the country—many owned by the property owner and not the utility—a significant shift from previous requirements for partial replacement.

Several agencies, in preparation for such rules, were already well on their way to cataloguing their infrastructure and replacing service lines, including realizing records were difficult to find or nonexistent.

For Denver Water, which had embarked on its own lead reduction program well before the federal changes were announced, the effort has involved combing through any existing records including a bound book of master plumbing documents which indicated about 1,300 service lines were lead. That wasn’t a lot of information for an area with about 300,000 service lines, but it was a start. Next, they looked at records from when the metering system was converted in the 1980s and scrolled through hundreds of microfiche records with handwritten abbreviations that might provide clues.

“Look at everything that you can,” advised John Nolte, Denver Water’s GIS manager.

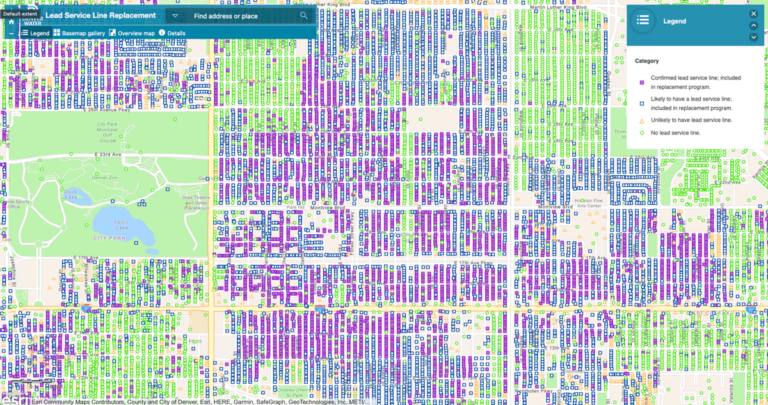

After one year, the utility’s leaders estimated there were 80,000 lead service lines. From there, they developed rules they could apply to determine the likelihood a lead pipe was currently present (ie: the age of a home, the tap, the home’s condition, when it was last renovated).

“GIS was one of the best tools for that,” Nolte said, because they could quantify the probability of lead pipe using GIS analysis and then mark it on the map.

In-person investigations, including water sampling and potholing—when the agency drills down at the street just enough to see both sides of the line coming into and out of the meter to determine the material—further reduced the number of possible lead service lines. In addition, calls to homeowners about upcoming water line replacements resulted in updates from some residents who had already replaced their pipes.

The current tally: 64,000 service lines would need to be replaced—16,000 fewer than the original estimate. That difference is expected to save Denver Water $50 million over the life of the 15-year replacement project, according to Nolte. The total price tag could be anywhere from $350 million to half a billion dollars, depending on fluctuating construction costs and supply chain issues.

Now, Denver Water is working to replace 4,700 lines each year using their own staff and several contractors to reach the goal.

Prioritizing which pipes are replaced first has been a scientific endeavor for some and a necessity for others, each aided by a geographic approach.

In Benton Harbor, property owner permission to enter their private property is driving the order of which pipes get fixed first. Collected in person, on tablets, the owners’ signatures green light when Abonmarche and their contractors can begin digging. It also allows workers to take before and after photos for record keeping. Without a GIS to record the information and make it accessible to all involved, Garcia said it would have meant nearly 5,000 paper forms and photos stored in physical files with minimal shared access.

Getting ahead of gaining approvals—in some cases it can take hours in conversations with a property owner to answer questions—would be essential for anyone tackling a similar endeavor, said Lucas Grosse, Abonmarche’s construction manager.

That’s where the regularly updated public-facing online dashboard showing where work has been done and how much is left has helped in communicating the project’s progress to residents.

“People can know what we’re doing and why we’re doing it,” Garcia said.

In Denver, the water agency has used machine learning in GIS to pinpoint where the largest concentrations of lead service lines likely reside based on the ages of homes and economic indicators of a neighborhood. Areas where owners may not have had the financial means to replace their lead pipes on their own would likely still have them, they’ve surmised.

It’s important to be as certain as possible that what’s underground is in fact lead before digging, said Nolte, because digging up the road, finding copper, and repaving “can get pretty costly.”

As for costs, agencies, cities, and states are keeping a hopeful eye on President Biden’s passed infrastructure bill that pledged $15 billion to states for lead service line replacements. An additional $11.7 billion in general funding may also be available, according to the EPA.

“It’s still so early,” Nolte said in terms of understanding how the bill might help his agency’s work. “It’s a really good way of hopefully obtaining some funding for this project.”

Learn more about how small water utilities apply GIS to improve service delivery.

May 27, 2021 | Multiple Authors |

August 24, 2021 |

February 8, 2022 |