June 4, 2021

Since the United Nations started World Environment Day in 1974, technological advancements have shown the ability to reflect human impact and lead to fixes for past misdeeds. Perhaps the next technology breakthrough will have gotten its first spark as an idea during this year’s Call for Code Global Challenge.

That’s the hope of two of the scientific community’s brightest minds—Esri Chief Scientist Dr. Dawn Wright and IBM’s resident “mad scientist” Dr. John Cohn—who recently met by video to talk about modern technology’s impact on the environment. They also discussed the role participants can play in this year’s Call for Code challenge that seeks solutions for combatting climate change. A prize of $200,000 USD will go to the winner. Esri, a global leader in location intelligence and conservation efforts, has partnered this year with IBM and the David Clark Cause, giving participants access to its ArcGIS mapping system.

The two met for a conversation with the Esri Blog, moderated by Esri writer Kimberly Hartley. Below is a transcript of their conversation, which has been edited for clarity and length.

Dawn Wright: One of the amazing things about this is the actual number in play here, as I think they identified 27,000 targets offshore Southern California that are thought to be barrels. It’s a wonderful AI example. When you’re doing that type of mapping on the ocean floor, you have to rely on acoustic signals which you can both bounce off the bottom and measure in terms of brightness, and that’s how they’re able to measure so many. They use machine learning to get through all of the thousands, and thousands, and thousands of potential targets in their acoustic imagery, to get to a much more accurate and confident assessment of how many of those things are down there. We’ve known about DDT barrels on the ocean floor since the 60s, of course, but now we’ve got some definitive numbers. And there’s going to be a multi-generational impact on humans potentially, not only the potential harmful impact of this DDT on the marine mammals and the other life forms in the ocean, especially because we eat many of the fishes from the waters. Talk about another fantastic engineering prize. How do you take the next step in cleaning up these huge, polluted areas on the ocean floor as you would similar places on land?

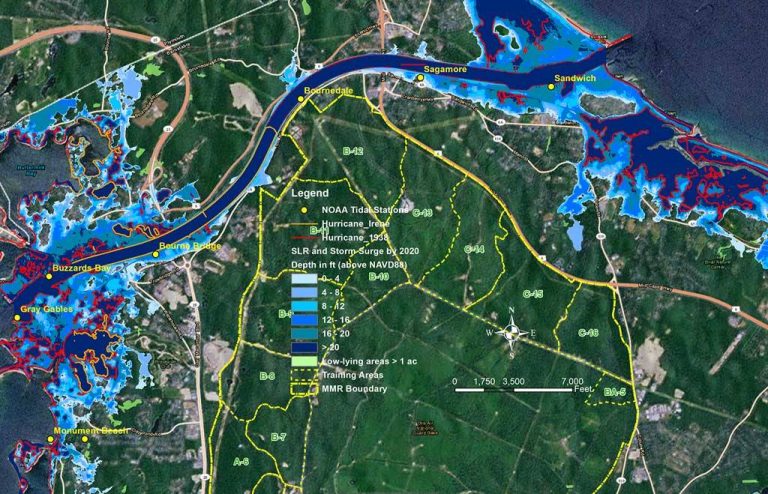

John Cohn: We have a big problem (in Vermont) with phosphorous runoff, and part of it is just our agricultural waste, manure, etc., but a lot of it is actually shipped in phosphorous fertilizer. So, what happens, is we get these giant stream runoffs and its starting to manifest as these blue green algae blooms in Lake Champlain. It’s quite deadly. What the protocol has been to date has been to go and take water samples by actually sending people out, and dunk, and pull the stuff back into a laboratory. But a colleague of mine at the University of Vermont, Professor Donna Rizzo, showed me some research using remote sensing, using satellite multi-spectral imaging and being able to detect the blooms at different stages and even get concentrations. They get ground truth from captured samples and from there build predictive models using open source data from satellites. AI can both show what our fingerprints are on the climate, but also help us evidently—because using the satellite data you can also see the sediment blooms. They can often trace the phosphorus runoff back to its source.

JC: I think the biggest advancement could actually come with new usage models and openness. I’m a huge believer in open source and open innovation. Both Dawn and I are talking about using remote sensing, like satellite sensing, that’s a very expensive proposition to put the satellites there but once they’re there, I think the biggest innovation could be in open platforms that allow people like at universities, or even high school students, to get time on those satellites, those remote sensors, and apply them in an open way. Coupling open access to these remote sensors with the advancement in AI and machine learning gives us an incredible opportunity for innovation and in public engagement. I know Esri does quite a bit of open source as does IBM, through initiatives like the Call for Code Global Challenge. I’d like to push us all to even do more. AI is being advanced so much by the technical generosity of all the open-source work that companies like Google, Facebook, IBM and Microsoft are all putting out there. We can do the same thing with sensing, and I think we’re starting to, in climate and weather, that would be a huge advancement.

DW: I was thinking along those lines, too, in the socio-technical sense. This was brought to light in a National Academy of Sciences webinar that I was in just yesterday, about responding to disasters during a pandemic. The geographic information officer for FEMA made a salient point about how ineffective AI was in helping them to manage some recent disasters, hurricanes especially, because, in the end, their problems were more around actual supply chains of real materials. They needed gloves, masks, ventilators, food items and more. And what was really more effective for them was the local social network, the person-to-person network. People were in the cloud, and they were trying to use resources in the cloud, including AI, to estimate the density of where resources should go to. But this still didn’t work as well for them as they would like. Why? Because right now, clouds—not all the clouds mind you—are not as open as you’re talking about, John, and further, these clouds do not talk to each other. And some of these clouds don’t talk to each other intentionally. Overall, it’s still not as open an ecosystem as we would like it to be.

JC: How do we incent that openness. It costs a lot to develop those infrastructures. How do you balance that?

DW: It’s the idea of generating enough goodwill by giving resources away, while still generating the revenue that you need to keep your business afloat. I think this is what allows you to be as open as possible.

JC: IBM has a network called Weather Underground which is part of the Weather Company. A few years ago, we used that platform to work with an organization called TAHMO – Trans-African Hydro-Meteorological Observatory in sub-Saharan Africa. Over three years, we helped them put in about 350 of their 650 high-accuracy weather stations in sub-Saharan Africa. The model TAHMO is taking is to try to enable both open and commercial use of that data. Part of their business is to monetize the data for agriculture and insurance. They’re a nonprofit but they’re trying to use financial input from the commercial use of that to make the rest of the platform available for research. The problem is that you’ve got to drum up enough commercial business to do that equation. So far, it’s working. They’re not getting rich doing it, but it’s working.

DW: When you are altruistic and you’re all about helping people to solve problems, that generates business too. You get customers from that as well. It is a very nice virtuous circle.

DW: I am absolutely confident that we’ll get all sorts of wonderful ideas. I’m hoping that I see efforts to build apps that are interoperable—working everywhere on everything to the extent that that’s possible, your phone, your tablet, a web browser, maybe even on your watch. But, also, it would be great to see some attention to translating between different languages in these apps. Because of the time and effort needed, this may not even be possible within the scope of this competition. But the idea of at least giving thought to different languages, age groups, and technical abilities, would be really nice to see. For example, there are over 200 languages spoken just in Los Angeles County. So, the various apps that we are trying to develop right now, in English, to meet various needs in southern California is of course effective, but it’s just a drop in the bucket in terms of reaching everybody in that one county, and further within this one state, within this one country.

JC: I really like what you were saying, how do we make it accessible, how do we do stuff to engage the public? I love citizen science. One of the things we’re trying to do is bring together as much open source, or freemium level commercial software and data into a common set of tools around Jupyter Notebook so people have a broad pallet to really get in there and play and try a lot of stuff out. I’m hoping that after the Call for Code event, they continue to do that. Because I think it’s a magnifying kind of thing.

DW: It sounds as though you’re talking about a sandbox, just a great big sandbox, for people to continue to play in, after the competition.

JC: It’s more tools in your toolbelt, so they can wake up the next day and say ‘you know, I’ve got this problem’ and know where to go.

DW: What I still see as missing is the thoughtful inclusion at the very start, with indigenous communities, rather than forging ahead with our cultural assumptions, and then coming back to their perspectives or languages or customs only at the end and trying to tack that on.

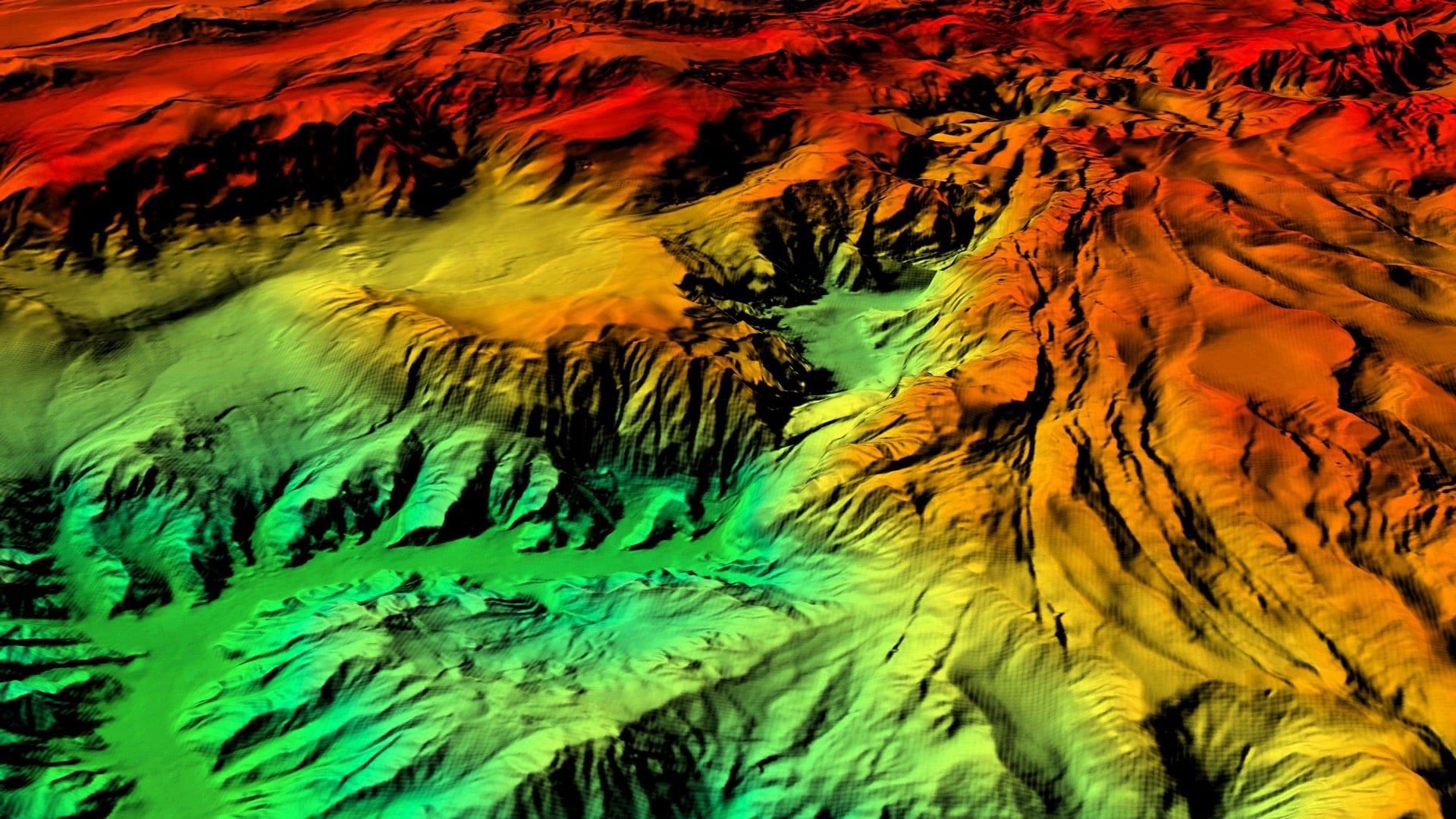

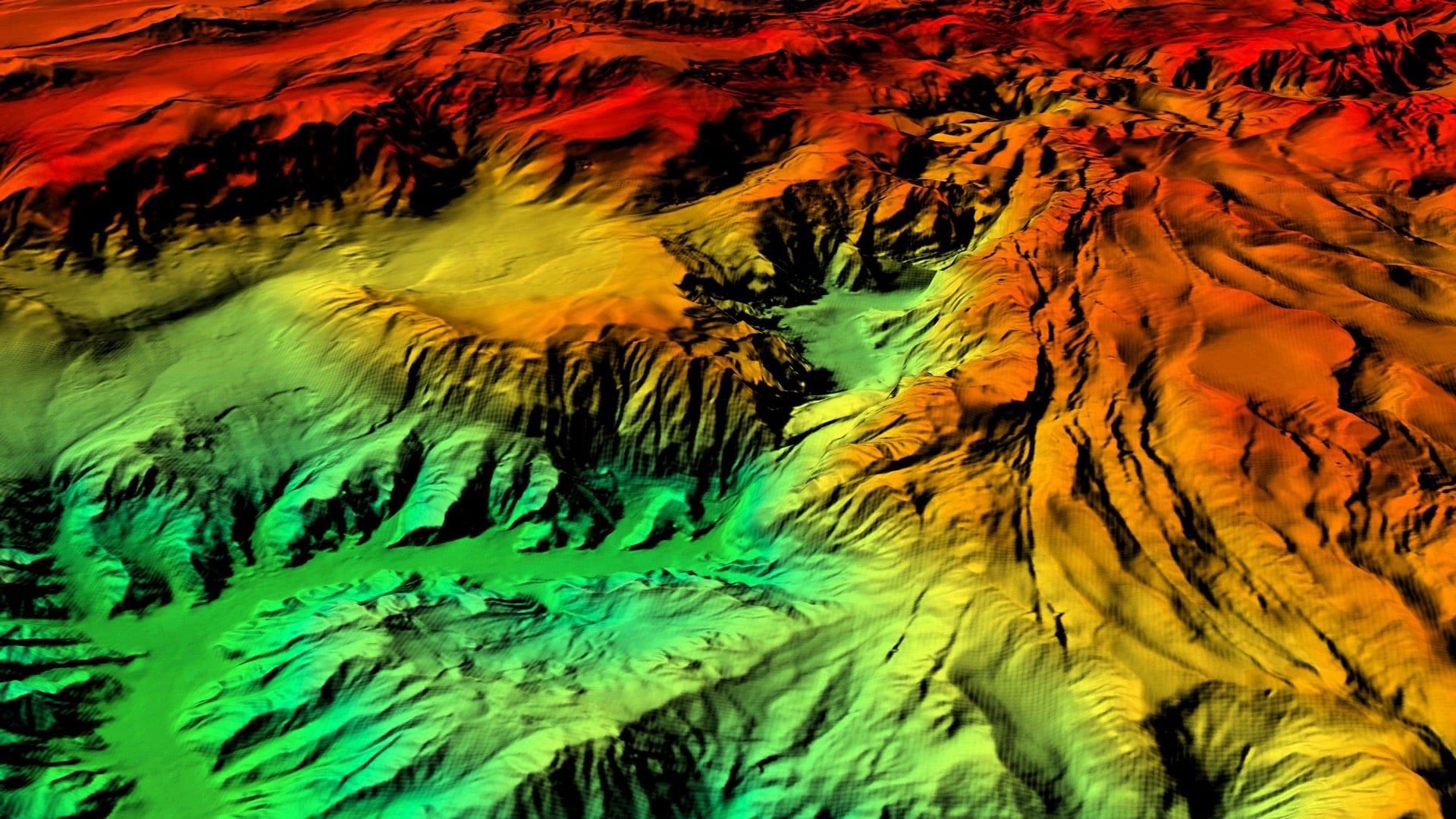

I also see a lot of tools geared toward spatial—we do this at Esri, of course, we’re the spatial people—but the temporal questions are left behind, especially with regard to conservation. We are running out of time. So many things are geared toward being fixed by 2030 and that’s less than 10 years away. There needs to be more of a nod toward detecting incidents that are happening within a certain time or reconstructing tracks to follow moving devices and assets. At Esri we’re working very hard on that, with spatiotemporal data cubes, including time parameters in almost all of our analytical functions now to allow the user to see the temporal distributions as well as spatial distributions; to help them understand trends over time.

So, including the time factor in conservation tools including those using AI, will definitely be a boon.

JC: One of the places where we can innovate is how we incent people to come up with good, potentially startup solutions, for cleaning up messes of the past. Instead of just in a contest framework which is sort of our go-to, how do we create national and international systems that incent people to come up with innovative solutions and provide funding for them, not just prizes? Often times, most times actually, these take a long time and a lot of trial, etc. Could we figure out how to provide capital and technology to people who have good ideas and have the incentives there so they can make a living doing that? It’s an interesting math problem. How do you make doing the right thing, make good business sense?

DW: That is such a great point. I’ve been on a couple of advisory committees for other prizes, which are real moonshots and the winners have solved some fantastic problems. But the follow-up process of commercializing these great solutions seems very long and difficult, and not all of them are successful.

JC: We want those big wins, but for all those big wins, we need a lot of small wins. Those are great because they inspire people and they eventually or occasionally come up with big solutions. But we need that at different scales. We need that at high school scale, startup scale, college scale, etc. So how do we actually start thinking about making that make sense, making that a good career choice for people to apply their STEM skills to solving problems.