The National Park City movement helps us with climate resilience by being smarter about what we develop and where.

July 1, 2025

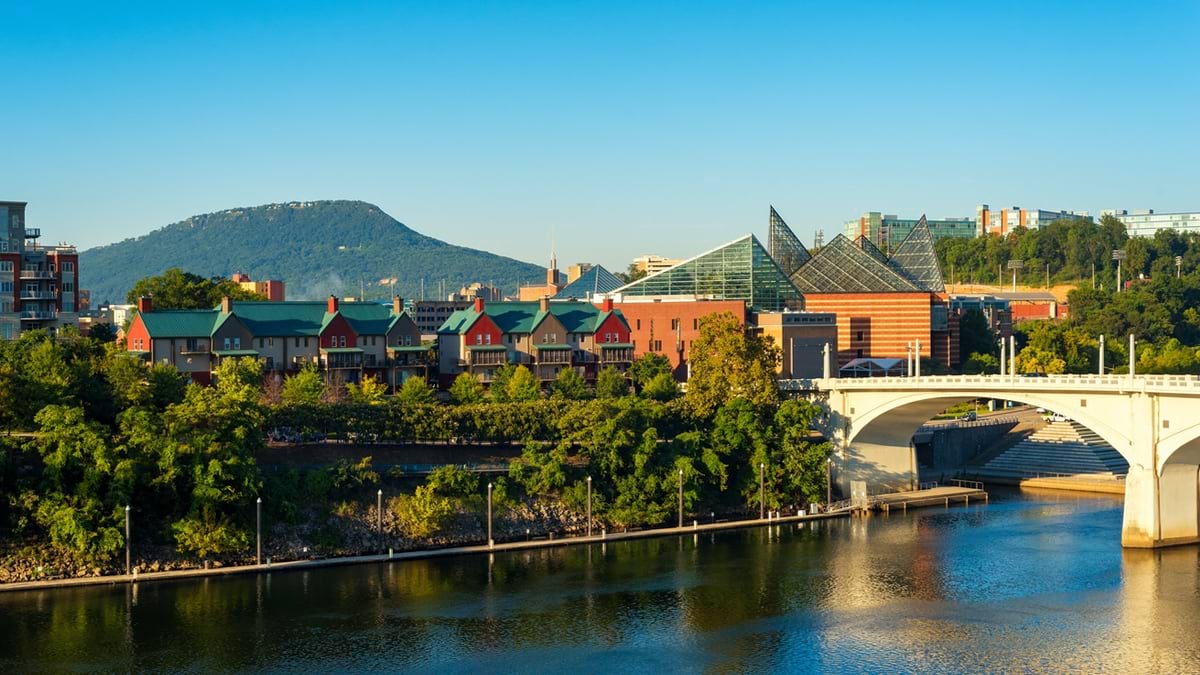

In the heart of Tennessee, where the Tennessee River cuts through Appalachian foothills, Chattanooga has achieved something remarkable—becoming America’s first National Park City. This honor reflects not just the city’s natural beauty, but a deliberate effort led by Mayor Tim Kelly to map strategies for conservation and economic development using geographic information systems (GIS) technology.

The mayor’s approach represents a shift in how cities think about their natural assets. Rather than view green spaces as amenities that compete with development, Chattanooga embraces what Mayor Kelly calls “living in a park with a city in it, rather than a city with parks in it.”

This philosophy, combined with sophisticated GIS mapping and analytics, helps the city quantify and protect what may be its greatest competitive advantage: It sits in one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet where opportunities for outdoor adventure abound.

Chattanooga’s story proves cities can serve environmental stewardship while driving economic growth. By mapping and analyzing its data with GIS, the city has discovered hidden assets, secured major federal grants, and attracted talent.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Mayor Kelly: When I was a docent at the Tennessee Aquarium back in 1992, I was in charge of the catfish tanks, learning about the more than 280 native species of fish in the Tennessee River. The aquarium hammered home to us that the Tennessee River Valley, where Chattanooga sits, is as significant as the Yangtze River Valley in China, the most biodiverse place on the planet. That’s shocking when you think about it. We don’t talk about that enough or recognize it widely enough.

That’s why all this conservation work matters. It’s why we’re putting such intentional focus on native species preservation. We’re also in the middle of a major flyway—my former parks director was a bird nerd and was delighted to learn that this is like Grand Central Station for birds. There’s a tremendous number of migrating birds that come over and through Chattanooga, contributing to our biodiversity.

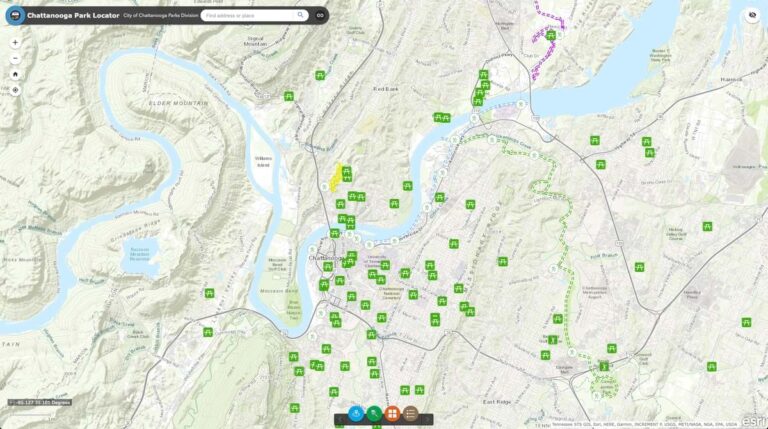

Mayor Kelly: One of the most frustrating things when I came into office was that nobody could tell me what we owned. There was no spreadsheet, no list of all the publicly owned buildings and property. They literally couldn’t provide that basic information.

I’m a map geek. In what little spare time I have, I poke around our county GIS site. I discovered a fascinating piece of land, a really unique oxbow, just by clicking around on our GIS map. When I clicked on it, I realized we owned it. That discovery led us to put that land into permanent conservation.

The same thing happened with Walden Park, which was this orphaned parcel that the city didn’t even understand it owned. We found it through GIS. Most of it was in the floodplain, so we made the decision to put it in permanent conservation. Once we realized what we had, we went through a public asset workshop to identify every parcel we own.

The National Park City movement helps us with climate resilience by being smarter about what we develop and where.

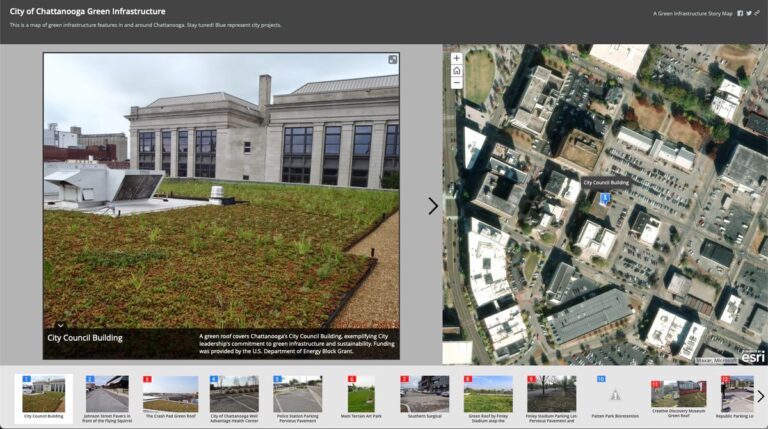

Mayor Kelly: The feds love data, and GIS allows us to quantify and communicate our situation effectively. As a mayor, I can’t spend all day driving around looking at stuff, but I can sit at my desk and look at a GIS map and learn a tremendous amount about my city. Then I can communicate those datasets so grant makers can make grants with a high degree of confidence.

Our GIS team, working with the team at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, has been instrumental in identifying our 5.3 million tree crowns within city limits and how we manage, preserve, and grow them. We didn’t even have a tree ordinance before, which was shocking to discover. The combination of detailed mapping data and clear conservation goals made our grant application compelling.

Mayor Kelly: Companies now have to go where their employees want to be, unless they’re fully remote—and if employees can be anywhere, why wouldn’t they choose the place with the best quality of life? The tourism pitch is now the same as the classic Chamber of Commerce pitch because talent has become the coin of the realm.

We’ve had over 1,000 people making $100,000 a year move here recently, which would be the biggest economic news in 20 years if they were all from one company. But they’re on this long tail—we don’t know who they are, there’s no club, no ID. I can’t go to one CEO and get them all. They’re just here because of all these natural assets we offer.

It’s fascinating—I keep hearing anecdotal stories of people who actually created spreadsheets, force-ranking different cities on attributes like outdoor access, arts scene, and quality of life. One guy told me he did this internationally and narrowed it down to us versus Geneva, Switzerland. It’s definitely a thing.

Mayor Kelly: A lot of the land we discovered through GIS mapping was in floodplains, which made the decision to put it in permanent conservation easier. Not only does this help with climate resilience, but it also provides opportunities for recreation when those areas aren’t flooded.

We’re also thinking more systematically about how our city can take advantage of these natural assets in an intentional way.

Many cities aren’t using technology effectively to identify parcels that could serve multiple purposes—flood management, recreation, and biodiversity protection.

Mayor Kelly: We discovered through GIS mapping that local churches have roughly 1,000 surplus acres that could be used for affordable housing. We would never have known this without the mapping technology. We were able to approach the faith community and say, “If you were to build affordable housing or senior low-income housing on some of this land, we could solve our affordable housing problem.”

We’ve got a couple of projects working on this approach. It’s been a very useful tool because we’re not competing with our conservation goals—we’re using land that’s already identified as suitable for development while preserving our natural assets.

Mayor Kelly: It starts with intentionality and recognizing your competitive advantage. For us, it’s these natural assets, so that’s the first organizing principle—both in terms of preserving physical assets and building the culture around them. Everything else proceeds from that understanding.

We try to be data-informed but values-driven. Unless the data is just loud and clear, you can spend a lot of time dog paddling in circles. You still have to be driven by your mission and values. We need more density where we need more density, but we also need to be very intentional about setting aside green space so Chattanooga can be the best version of itself.

You also need the technology to identify what you actually own and manage. Most cities probably have assets they don’t even know about. The combination of GIS mapping and clear values about what you want to preserve creates opportunities you never knew existed.

Mayor Kelly: People tell me Chattanooga reminds them of Austin 30 years ago, and I always respond that the trick is to keep it Austin 30 years ago.

We need to develop benchmarks to measure our progress and ensure we maintain that balance. We’re looking at creating more connectivity between neighborhoods through paths and our riverwalk system. We want to build on our momentum while being very deliberate.

The goal is to show other cities that reverence for nature isn’t just good environmental policy—it’s good economic policy. When you can quantify your natural capital and communicate its value, you create a sustainable competitive advantage that benefits everyone. That’s the story we want to tell, and that’s the model we hope other cities can adapt to their own unique natural assets.