Having a spatial context—combining knowledge of land and people—is really integral to moving Philadelphia forward

March 27, 2019

This story is part two of a two-part series that examines the impacts of Philadelphia’s renewal policies. The first installment explores the impact on vulnerable populations.

In the early 2000s, few cities would have chosen to swap places with Philadelphia. The city confronted major economic hardships and a massive volume of derelict and declining properties. A report estimated that 40,000 vacant or abandoned properties were dragging the city down.

The Philadelphia City Council acted with a series of anti-blight policies, including a tax abatement incentive that let property owners avoid paying taxes on property improvements for ten years. These policies helped renew neighborhoods and have contributed to a city on the rebound.

With renewal well underway, but uneven, the Philadelphia City Council has begun to explore the implications of these policies on its residents.

“The abatement has done its job to spur development, but maybe it’s done it in a way that’s creating problems for us now,” said Herb Wetzel, director of Housing and Community Development, Philadelphia City Council.

Examining Redevelopment Patterns

When Philadelphia City Council passed the tax abatement program, it very consciously allowed developers to pick anywhere in the city to redevelop and did not cap the abatement limit based on the value of the property.

The tax abatement applies to commercial, industrial, and residential properties. If it’s an existing building and you spend $2 million to improve it, the $2 million gets abated.

“When people read that somebody bought a $12 million condo and they’re paying taxes on $500,000, it’s upsetting to them,” Wetzel said. “The most important thing we could do was add to the content of the discussion by showing where redevelopment started and where it’s moving.”

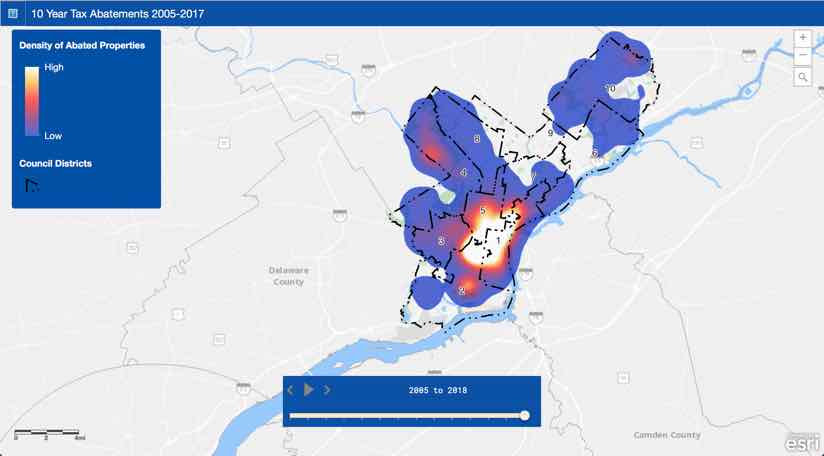

The city’s geographic information system (GIS) provides the means to explore the city’s renewal on a map. It allows the user to look at neighborhoods and individual parcels to see when an abatement was issued, the history of property taxes, the land value, the improvement value, and how much of the property is abated.

“We looked at the tax abatement through space and time to see where the program was having the most effect,” said Greg Kingery, GIS analyst with the Philadelphia City Council. “We could see the growth in and around Center City, confirming the suspicions of staff and council members, and informing the policy discussion.”

Fine Tuning the Incentive

Looking at the past 20 years of development, the City Council has started asking whether the city has been subsidizing the right mix in the right areas. The spatial context—viewing details on a map—adds a crucial element to the discussion.

“In terms of understanding the distribution of the abatement, we know that 80% of the abatements issued since 2005 have been in three council districts,” Kingery said.

The City Council has also begun querying the demographic shifts within the city.

“In 2000, we had a thriving Center City in Philadelphia with about 100,000 residents and most of the surrounding neighborhoods were predominantly African American working class,” Wetzel said. “Now, we have over 200,000 people living in Center City and most of those working-class African American neighborhoods have or are in the process of being gentrified.”

The Graduate Hospital neighborhood provides one example. It was 90% African American in 1980, 72% African American in 2000, and 22% African American in 2016. The neighborhood contains 2,300 abated properties.

“There’s a connection between providing abatements and changing demographics,” Wetzel said. “Has the 10-year abatement become more than an economic stimulus and created jet fuel for gentrification?”

With these outcomes becoming clearer, three bills have been introduced to City Council to adjust the abatement program.

Having a spatial context—combining knowledge of land and people—is really integral to moving Philadelphia forward

Compounding Incentives

In 2017, the Tax Cut and Jobs Act passed by Congress created a federal Opportunity Zones program to spur private sector investments in low-income urban and rural communities nationwide. This program gives investors with capital gains tax liabilities a mechanism to reduce their taxes by investing in an Opportunity Zone designated by each state.

In Pennsylvania, a similar statewide program has been in play since 1999 with the Keystone Opportunity Zone program. The program offers tax abatement for state business taxes and other local business taxes if businesses relocate into these areas, invest in renewal, and create jobs.

Some of the Federal Opportunity Zones overlay the Keystone Opportunity Zones, and in Philadelphia the local tax abatement is still in effect. This means that a developer could triple dip into these programs in the city and reap compounding tax savings.

As cities around the country contemplate the implications of the federal Opportunity Zones, Philadelphia’s experience and its policy evolution stand as a good example for monitoring and analyzing impacts of these tax incentive programs.

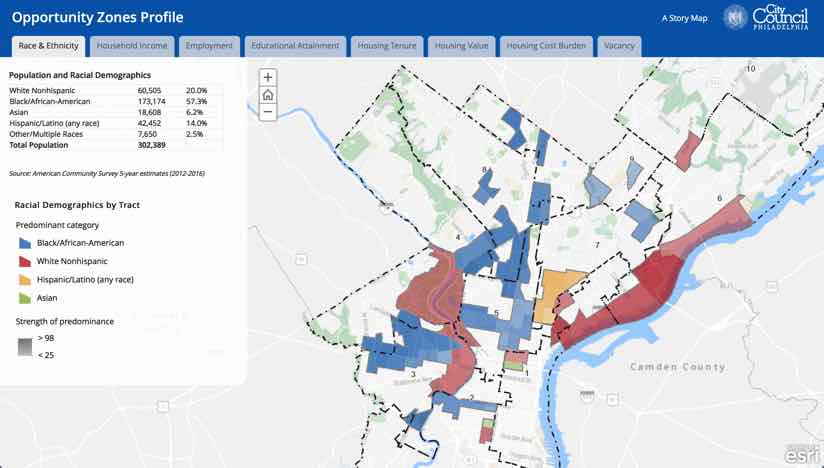

“We recently held a hearing on the federal Economic Opportunity Zones for council members,” Kingery said. “As everyone tries to understand the ins and outs of the Federal Opportunity Zones, the map helps inform the relation of the zones to council districts, who lives there, and how they might be impacted by development.”

The presentation included a Story Map with a set of demographic tabs across the top to display ethnicity, education level, median income, and housing values. With a council district overlay, council members could look at their districts and the people that will be impacted.

“Having a spatial context—combining knowledge of land and people—is really integral to moving Philadelphia forward,” Kingery said.

Ongoing Analysis

The property tax abatement does take out a chunk of revenue from the city for ten years, but other taxes contribute to the city’s coffers.

With all of the construction, permit and licensing fees have increased. A local income tax for residents and non-residents has grown with the growing population as well as from the construction workers. The people who move into the renewed housing also add to the city’s sales and income tax.

With many of Philadelphia’s ten-year tax abatements coming to a close, the City Council has plans for the renewing tax funds.

“We share the property tax with the school district, and the city’s share of that tax is committed to affordable housing,” Wetzel said. “For just this year, that’s $19 million more for affordable housing.”

Learn more about how GIS supports planning and development.

March 21, 2019 |

February 5, 2019 |

October 31, 2017 |