July 15, 2025

The Caribbean, a tapestry of island nations and developing economies, relies heavily on coral ecosystems. Corals in this region and worldwide are under duress, and now scientists are using an AI-powered 3D model—an environmental digital twin—to protect this vital resource.

Vibrant reefs, teeming with exotic marine life, are the main draw for a $50 billion Caribbean tourism industry. These rich, delicate habitats also provide food security for the region’s 43 million people. Symbiotic mangroves protect roads, farms, marinas, and hotels against the battering of tropical storms strengthened each year by rising ocean surface temperatures.

Since the 1950s, coverage of living coral has been cut in half. At least 63 percent of associated biodiversity has also declined. But corals have shown surprising resilience, especially when governments and industry leaders embrace sustainable development measures.

“Conservation isn’t an easy task,” said Steve Schill, a geospatial data scientist with 23 years of working in the Caribbean. “It’s a very complex problem, and it has a lot to do with people and changing behaviors.”

For Schill, who leads science operations in the Caribbean for The Nature Conservancy (TNC), solving the problem starts with a complete map. He and his team— Valerie Pietsch McNulty, Catherin Cattafesta, and Denise Perez—have built an environmental digital twin that shows a detailed, data-rich picture of every reef ecosystem dotting the sea. It combines geographic information system (GIS) technology and remote sensing—data gathered from sensors, satellites, drones, aircraft, and underwater cameras— to zoom in to intricate details of reefs, mangroves, and seagrasses.

It also zooms out to reveal the deep interconnectedness of shallow water ecosystems. The goal is to map in detail where these ecosystems are, understand their condition, and monitor changes over time. This insight is crucial for effective adaptive management.

Digital twins—virtual representations of complex systems—are common in manufacturing, utilities, airports, and cities to gain a holistic understanding of many moving parts.

Conservationists have also embraced environmental digital twins to focus on urgent issues, such as ecosystem restoration and the eradication of invasive species. Built with GIS, these twins capture critical environmental data and create a working model of natural communities and ecosystems to monitor health and find balance. Coupled with environmental sensors and AI, the digital twin accelerates understanding of natural processes.

The Caribbean digital twin created by TNC captures over 200,000 km2 of shallow-water habitats across the entire region. Imagine a mosaic of 35,000 satellite images that each capture a 150 km2 block of land or sea. Scientists use the digital twin to measure the health of carbon-capturing mangroves and seagrasses. This data provides a time stamp to monitor changes in the future.

Images from Planet Labs, a San Francisco-based earth imaging company, give conservationists a highly granular view of shallow-water habitats up to 30 meters below the surface. Daily optical images are transmitted by a constellation of shoebox-sized Dove satellites. New Tanager satellites have hyperspectral cameras with hundreds of bands—useful for advanced detailed monitoring of greenhouse gases, vegetation health, and plant and animal species.

Developing a cloud-free mosaic of thousands of satellite images took over a year. Each scene had to be searched in a vast archive. The best scenes were cloud free and included calm waters, low sun glint, and consistent light levels needed for accurate spectral analysis. These scenes were standardized for brightness and contrast using advanced color correction techniques based on AI-powered image analysis.

The result is thousands of miles of ecosystems captured in vivid detail and rich with data. For the first time, stakeholders can have a consistent regional map of coastal habitats. They use the data to zoom in and identify health indicators like water clarity, mangrove density, coral structure, and the presence of algae and other organisms. Applications track exactly where mangroves are dying and where they’re thriving—and help managers decide what to do next.

Satellites and AI have expanded their capabilities, but marine conservationists prefer to strap on their scuba gear for precise monitoring. In remote sensing, you need to couple and calibrate the imagery with field data.

“This allows you to produce a map with higher accuracy and gives you confidence in your results,” Schill explained. “Those are the two ingredients for creating a good map—an optimal image and lots of field data.”

TNC conducts extensive field operations, often in partnership with local groups. Drone flights provide a closer look at patterns picked up by satellites. GPS-equipped underwater cameras help document aquatic habitats affected by bleaching. Field data is georeferenced with GIS and layered onto satellite basemaps.

Having field data and satellite images in the same view enriches the analysis. Coral dispersal patterns can be modeled across hundreds of miles. Problem areas can be highlighted—when bleaching events may result in coral reef loss, or a hurricane may damage a mangrove forest. Geospatial AI models, trained on ArcGIS spatial data, predict how human activities can lead to different outcomes as patterns on the map.

“One of the challenges is having countries look beyond their own borders and consider regional connections that are important to maintain,” Schill said. “Marine species don’t care about country borders, and require collaborative regional protection.”

Conservationists work at various scales mapping and analyzing ecological processes. For example, coral outplanting—where temperature-resilient corals are grown in a nursery and replanted on the reef—uses data collected at multiple scales to identify the best places where coral is likelier to survive. TNC scientists can detect changes in coral at the millimeter level, using in-water stereo photos for detailed 3D models of research plots.

Drones—flown 60 meters above the water—are also used to map coral colonies at the centimeter level, scanning larger areas for live and bleached corals. Aircraft mounted with special sensors can be used to fly higher and map national-scale features at submeter accuracy. Satellites are used to map features at the regional scale at coarser resolutions.

“One scale is not more important than the other,” Schill explains, “To understand the big picture of what is going on, you need information at many scales to fully track ecological processes.”

In many underresourced countries, conservation efforts often take a back seat to more immediate needs and limited resources. New and innovative financing mechanisms are opening fresh revenue streams for implementing conservation actions.

For example, Barbados has recently unlocked conservation funding through TNC’s Nature Bonds, a customized debt-restructuring program to finance a nation’s ambitious conservation goals. Barbados has committed to protecting 30 percent of its marine space and will be receiving $50 million to support management of these areas over the next 15 years.

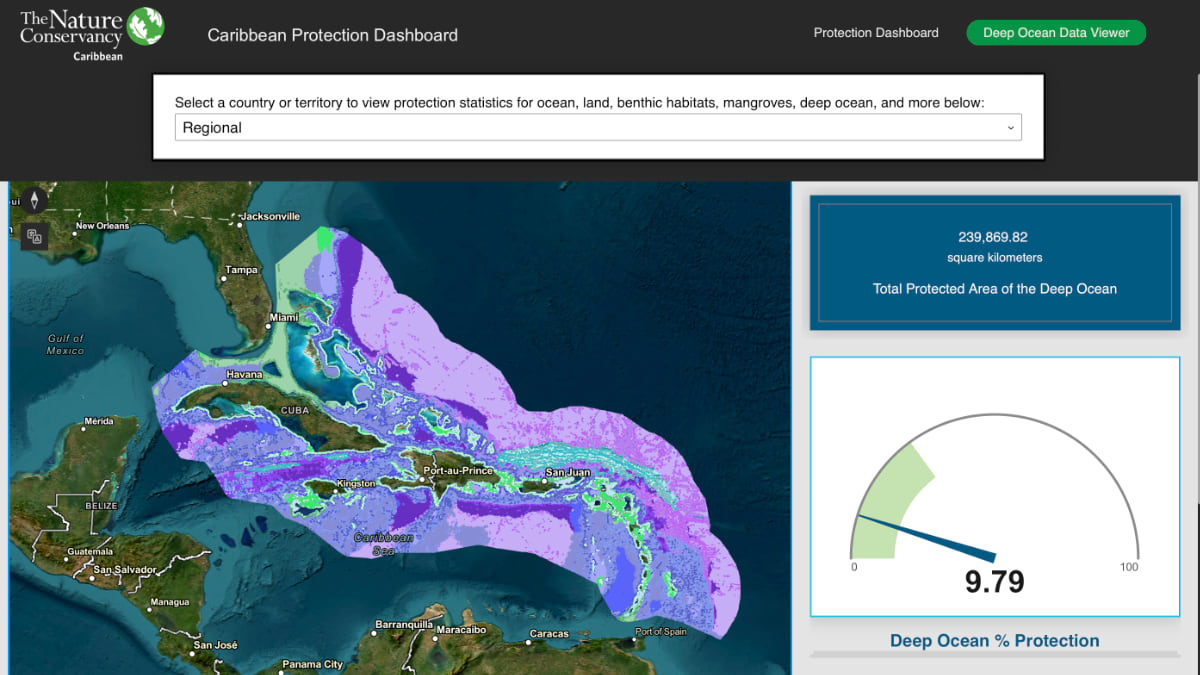

Efforts to better manage the oceans and reduce conflicts in marine areas are being made through marine spatial planning. This approach is becoming more common around the world. Science is central to deciding where to set up new marine protected areas. It helps countries meet their 30×30 biodiversity goals under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. “We’re working with countries to move the needle on ocean protection,” Schill said. “We need to speed up ocean protection using the best science to find the most important areas, while considering the needs of different industries.”

Since conservation decisions are largely based on data, sharing data is a critical component in achieving region-wide conservation goals. “We’ve created a lot of data over the years, and we’re using Esri technology to be able to search and provide that data to the world,” Schill said.

TNC’s Caribbean Science Atlas contains hundreds of maps, apps, and data layers—collected, managed, and shared with GIS—that help sustainable development initiatives snap into place.

Sustainable development is fundamentally linked to better land and ocean management. In a world too often driven by short-term political wins, poor choices lead to environmental degradation. The right decisions start by asking where: Where can we build the coastal resort that will cause the least amount of damage to coral reefs and mangroves? Where do we restrict fishing to replenish our stocks? Where can we plant mangroves that will reduce floods’ impact on people?

“We’re really trying to get governments to understand the value of investing in coastal ecosystems because of the economic and social benefits they provide to people. Government leaders have to make hard decisions,” Schill said. “Our goal is to deliver data and tools that foster better decisions that preserve both economic and environmental interests.”

GIS maps and models provide a highly effective way to present rigorous scientific analysis that stakeholders can understand at a glance.

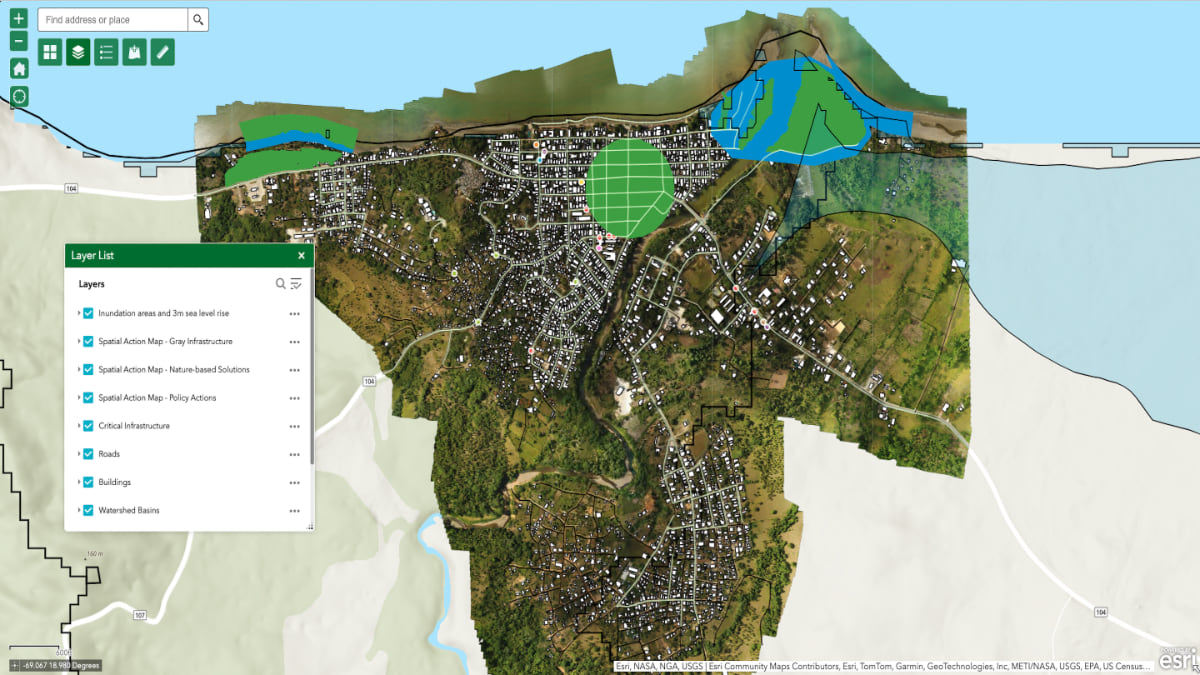

When the Jamaica Red Cross wanted to direct disaster preparedness funds allocated for Old Harbour Bay, a highly vulnerable community on Jamaica’s southern coast, the organization partnered with TNC. Schill’s team conducted a rapid assessment of corals and mangroves, using satellite imagery, drones, drop cameras, and hydrographic survey data to document the role these habitats play in protecting people from storms and floods.

Schill and his team worked with residents to create an ultradetailed map of key buildings, roads, and drainage systems. “We mapped out everything—building infrastructure, coral reefs, mangrove forests,” Schill said. “We then modeled areas that were more likely going to be flooded based on different scenarios.” Adding population density and demographics data to the assessment, they calculated where the community was most vulnerable.

This map, layered with so much information, expressed a data-driven answer to the Red Cross’s highly complex question, Where do we invest in nature to help protect people? It created a road map of where to direct funds for restoration activities that would have the best return on investment.

Meanwhile, in the Dominican Republic, intense storms and powerful downpours were washing away critical infrastructure, leading to tragic deaths and injuries. Agricultural expansion had led to the reduction of forests that once played a crucial role in absorbing floodwaters rushing down from higher elevations.

In the past, hydrology modeling meant setting up flow meters on hillsides and waiting for the next storm. Now, with satellite- and drone-enhanced geospatial analysis, Schill and team had a faster way to draw flood boundaries. Stakeholders could view flood data in the context of built infrastructure and population centers.

“This is all about reducing the impacts of flooding, and designating areas that ecologically should be restored,” Schill said. “And that will help us design nature-based solutions to these problems.”

Nature-based solutions—like planting mangroves and implementing green infrastructure to manage stormwater runoff—are often more sustainable and cost-effective than traditional gray infrastructure.

“The needs are different from country to country in terms of the tools and resources that they need to advance,” Schill said. “We continue to work collaboratively and demonstrate that an investment in nature is going to pay off.”

Maps provide a powerful way to make the case.

Twelve Caribbean countries, including Jamaica, Grenada, Antigua, and the Bahamas, have committed to preserving 30 percent of their ocean and land territory by the year 2030. Geospatial digital twins, powered by remote sensing and AI, help leaders identify the 30 percent of land and water that can be protected most effectively.

“We’re not going to back down on these goals,” Schill said. “Countries have set an ambitious agenda for themselves, aware of the connection between marine protection and economic health.”

As the calendar moves toward the next decade, maps and dashboards track progress. Percentages of preserved land increase as countries add new protection zones to the map. “It’s a little peer pressure to try to get them to mobilize and advance quickly towards the 30 percent goal.”

Tools like Marxan have proved helpful in determining the most impactful areas for conservation. Each country has its own points of emphasis, and TNC synthesizes information attuned to the countries’ unique goals and planning processes.

Significant progress has already been achieved. Since 2008, protected-area coverage has almost tripled. Region-wide, more than half of the mangroves are under protection, as is over a quarter of the coral reefs. With rapid tourism growth, the Dominican Republic has more than half of its reefs and almost 80 percent of its mangroves under protection. Saint Kitts and Nevis have declared the first national-scale marine spatial plan. The Caribbean Biodiversity Fund is providing sustained funding to a broad range of countries seeking to protect and manage critical habitats.

As the conservation agenda advances, GIS will continue to play a crucial role in providing powerful data and tools for answering this question: Where are the most important places to protect?

Learn more about how conservation groups and scientists team up to protect biodiversity with GIS.