November 10, 2025

How Real-Time Intelligence Is Dismantling Environmental Crime Networks in the Amazon

A new approach to environmental law enforcement in the Amazon basin is cutting into the criminal networks that exploit the region’s rich natural resources and diverse wildlife. Officials from Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru are working together through the International Initiative of Law Enforcement for Climate (I2LEC)—a program backed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that gives them shared situational awareness from one real-time map to carry out massive operations.

Across the dense Amazon jungle, illegal mining, logging, and poaching activities have exploited gaps in jurisdictional enforcement. These borderlands were places rangers rarely patrolled. Clouds often obscured the view from above and satellites infrequently gathered images.

Law enforcement across borders had been slowed by bureaucracy. But agencies around the globe are now collaborating via the I2LEC platform, which centers operations via a common operating picture—a map powered by geographic information system (GIS) technology. Bordering nations use the same GIS platform and mobile applications to securely share data and coordinate operations.

-

Officers discover heavy excavation equipment hidden deep in the protected Amazon rainforest. Criminals use excavators to strip-mine pristine jungle areas for mineral extraction.

Solving the Coordination Problem

This new system was the vision of Guillaume Alvergnat, an adviser within the UAE Ministry of Interior and a key architect of I2LEC. The problem wasn’t a lack of effort or expertise—it was that criminal networks moved faster than enforcement agencies could coordinate a response. I2LEC solved this by giving every participant, from field operators to command centers, the same real-time operational picture, effectively collapsing coordination gaps.

With backing from the UAE, I2LEC’s GIS mapping platform brought together three core capabilities that had never worked in concert against environmental crimes:

- Spatial analysis revealed where criminals hide in law enforcement gaps

- Real-time awareness compresses coordination from weeks to hours

- Mobile tools enable rangers in remote areas to share photos, videos, and observations with crime analysts

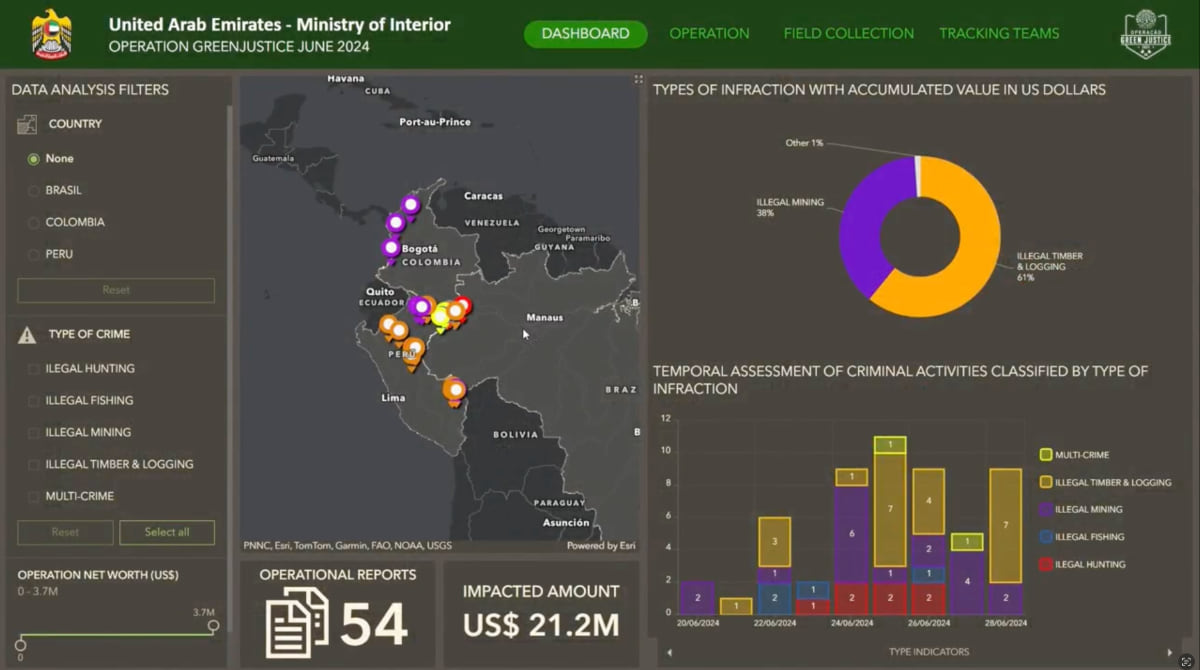

When teams layered satellite imagery of active illegal mining sites with data on the current locations of law enforcement presence, a pattern emerged. They could see illegal operations clustered at jurisdictional boundaries.

They could also see the fuel supply chain that sustains deep-jungle mining operations by combining fuel theft data from one country with transport route anomalies from another and equipment location data from another. When these datasets lived in the same spatial platform, the entire supply chain appeared.

“The stealing of fuel is kind of the linchpin for all of it,” said Alvergnat. “To get that big equipment into those deep areas requires a whole network of fuel theft, fuel transport to energize those machines doing the destruction.”

-

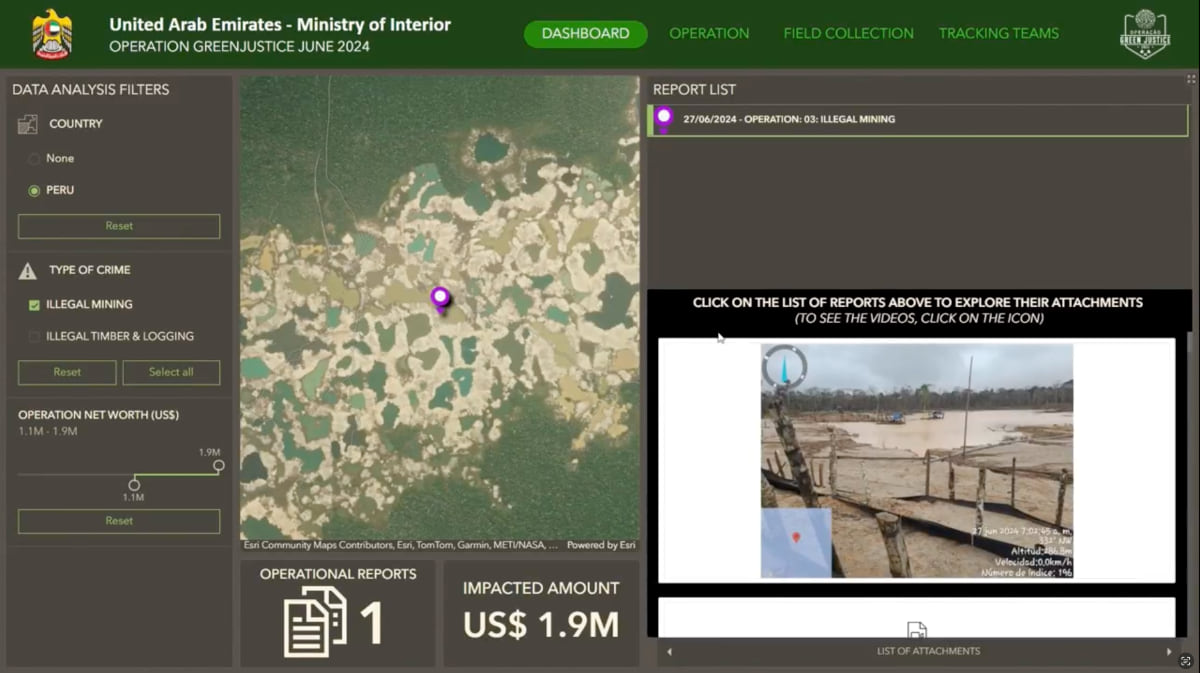

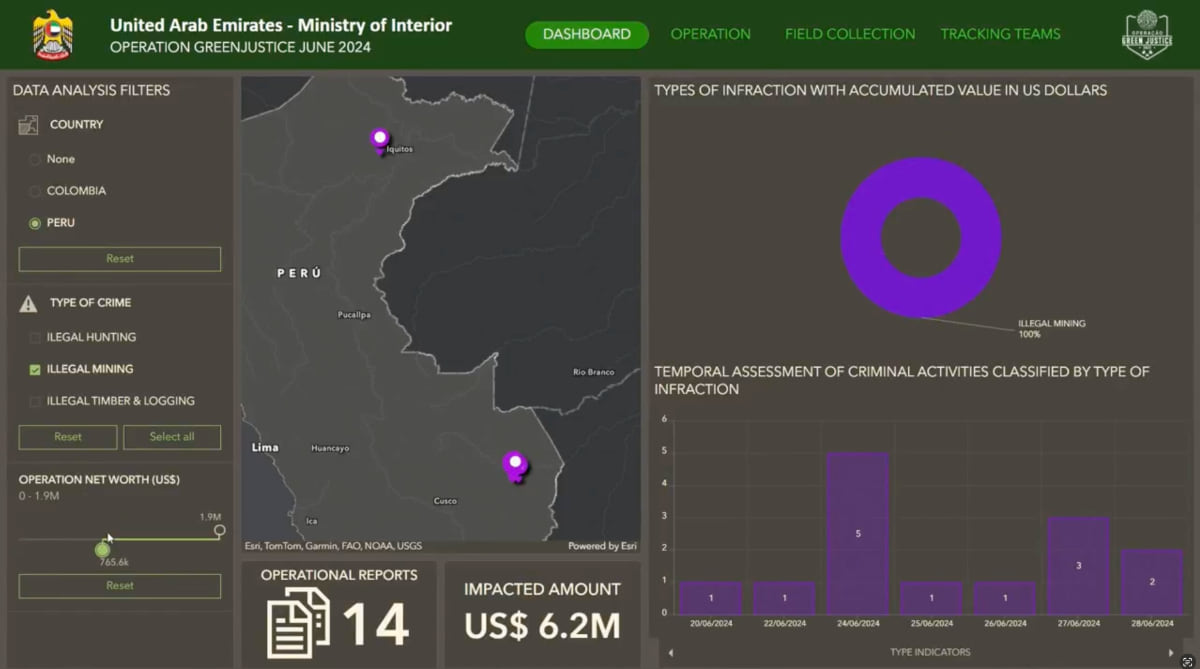

UAE Ministry of Interior's I2LEC command center displays real-time Operation Green Justice intelligence, tracking $21.2M in seized criminal assets across 54 enforcement operations.

No single jurisdiction could see it, but pulling all of that shared data together onto one GIS map made it impossible to miss.

During operations, transnational teams align around a real-time common operating picture. Field agents in remote jungle locations, helicopter pilots in the air, and analysts in the operations center all share the same view. Rangers operating without reliable connectivity can collect observations offline—photographs, GPS coordinates, field notes—then sync when they return to coverage.

Unprecedented Scale and Complexity

Cross-border collaboration supported by I2LEC is happening across Asia and Africa as well. In the Congo basin, coordinated enforcement has disrupted elephant ivory trafficking networks. In Asia, the same GIS platform tracks illegal timber operations spanning multiple countries. But the Amazon operations represents the largest deployment of this approach to date. The challenge wasn’t just the scale—millions of acres across Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru—but the operational complexity.

Criminal networks had learned to exploit the fact that enforcement stopped at borders. They could mine in Brazil, process in Peru, transport through Colombia, and move contraband through Ecuador. If law enforcement from one country disrupted one part of the network, the rest would adapt and continue. The criminals understood spatial relationships instinctively—where to operate, how to move, which gaps to exploit. They operated as a network across jurisdictions while enforcement was constrained by jurisdictional barriers.

That changed when law enforcement across all four countries could see the same information simultaneously.

-

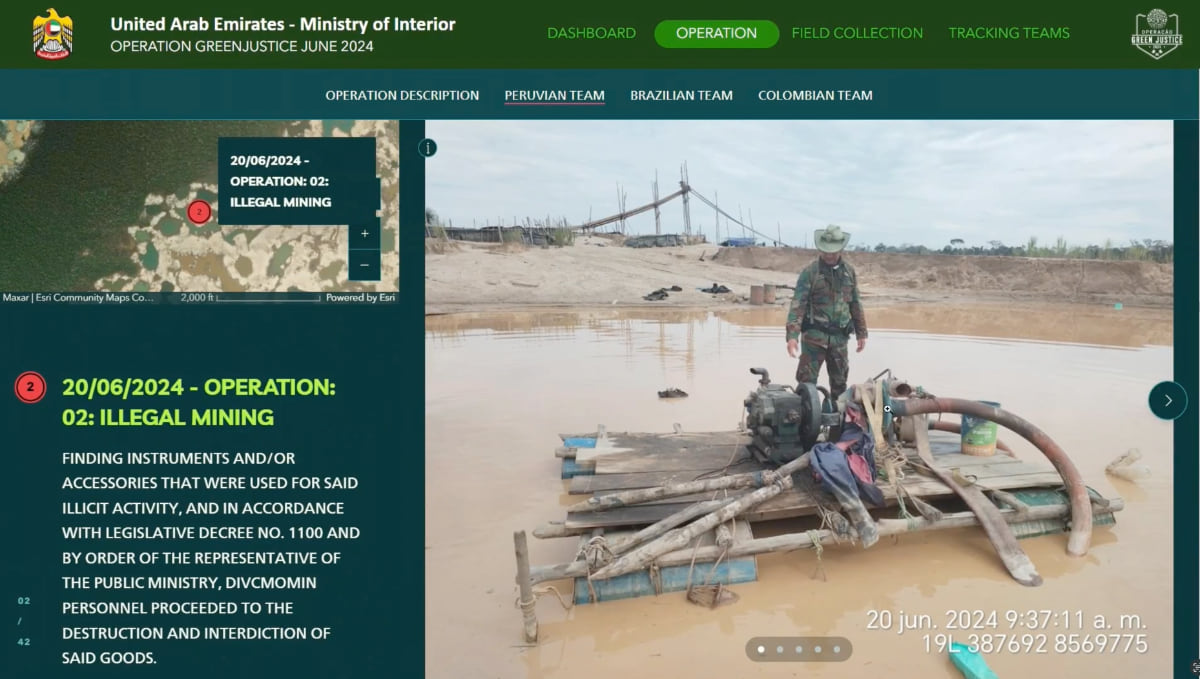

A law enforcement officer conducts the controlled destruction of illegal mining machinery during Operation Green Shield, eliminating criminal infrastructure used in Amazon environmental crimes.

In the Bogotá operations center, Brazilian helicopters approaching an active illegal mining site triggered immediate responses. Peruvian teams moved to intercept wildlife traffickers; Colombian enforcement identified exit routes. Not from reports, but because everyone saw the same map updating in real time.

In preparation for the operations, satellite imagery detected deforestation that ground teams used to confirm illegal mining activity. Transport specialists identified the supply routes. All this information lived in the same GIS platform, visible to every participating country to coordinate their responses.

Arrests in one area by the different teams became visible simultaneously, giving enforcement the ability to act before criminals elsewhere could adapt and scatter. When enforcement moved in on a mining site in one location, teams in neighboring jurisdictions could block escape routes. When analysts identified a new supply route, field teams received updates directly.

Alvergnat described the shift: “We’re all coordinating with the same tools, with the same awareness. That just cuts through all that bureaucracy.”

Learn more about how law enforcement agencies use GIS to manage field operations, power real-time situational awareness, and drive cross-jurisdictional crime fighting efforts.

Related articles

-

February 20, 2024 |

February 20, 2024 |David Gadsden |Conservation -

November 2, 2020 |

November 2, 2020 |David Gadsden |Conservation Chengeta Wildlife Wields Location Intelligence to Fight Poachers

-

March 31, 2020 |

March 31, 2020 |John Beck |Public Safety Antiquities Trafficking: Maps Take Aim at Looters and Buyers