January 11, 2022 |

April 27, 2022

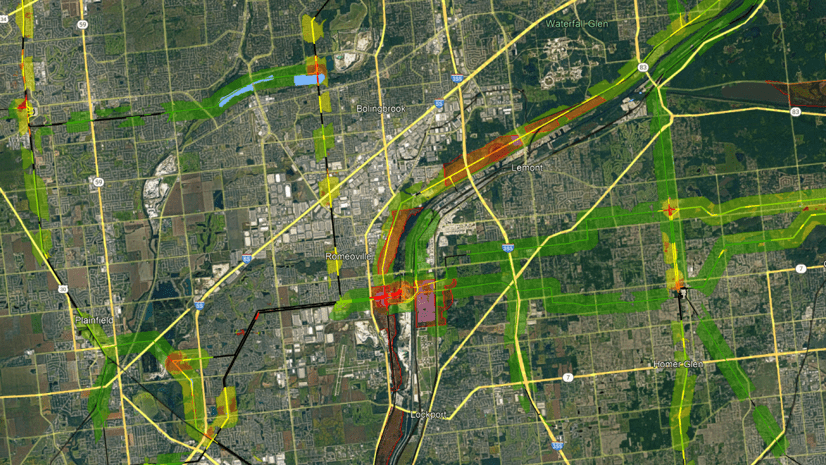

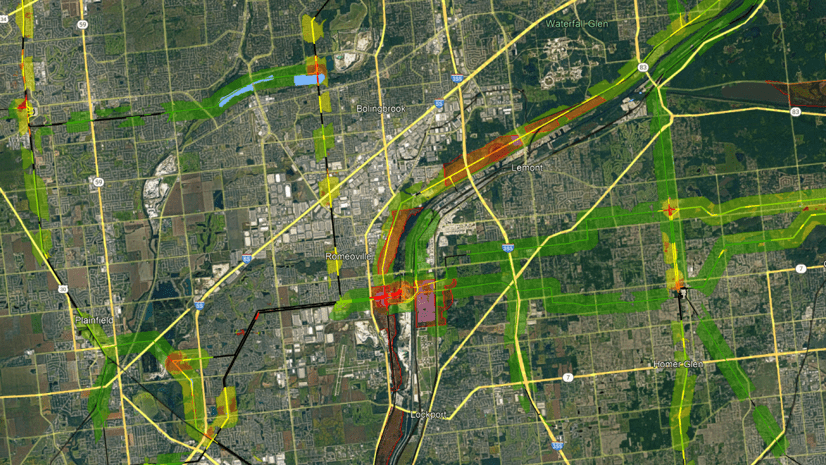

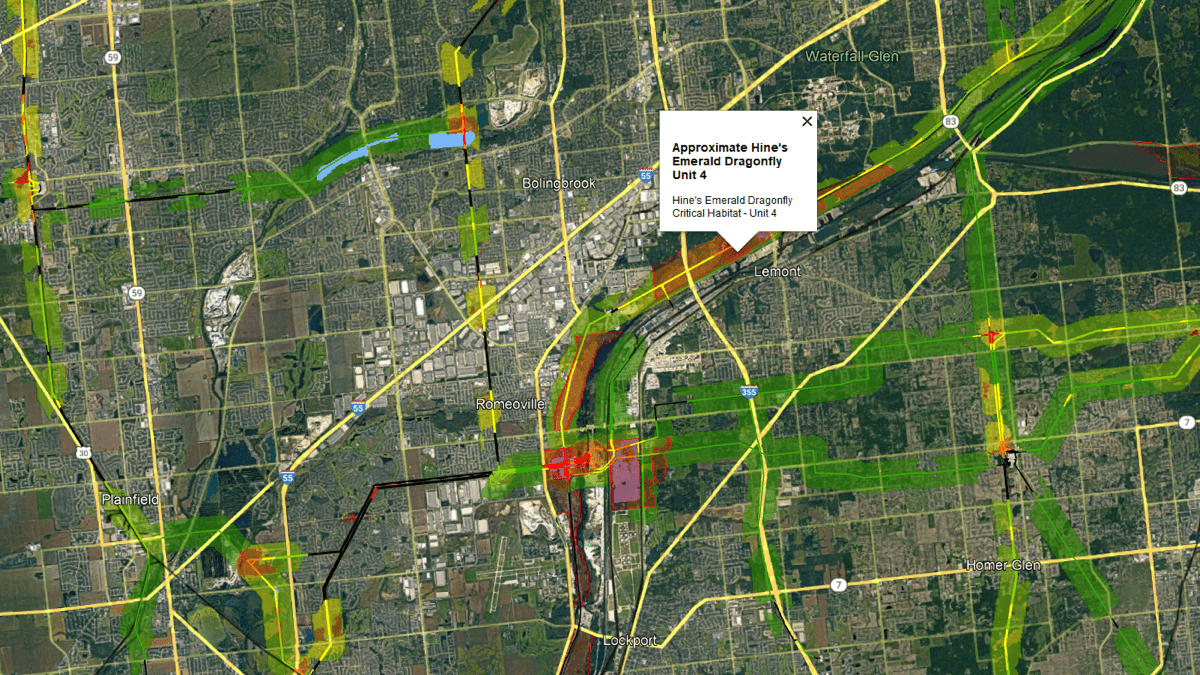

Electric transmission lines in northern Illinois cut through the Lockport Prairie Nature Preserve, one of the few remaining habitats of the endangered Hines emerald dragonfly. This rare insect stays underground for its first five years of life, making it particularly vulnerable to changes on the land above. To keep utility maintenance from harming the dragonfly, staff at Commonwealth Edison (ComEd) carefully crafted a habitat conservation plan that included the use of smart maps to remove lines to avoid conducting maintenance in sensitive areas.

Avoiding land that the Hines emerald dragonfly occupies helps the utility as well—eliminating the cost of complying with the strict protocols of the Endangered Species Act while simplifying land management.

ComEd’s conservation efforts serve as an example of how organizations can use technology to be both profitable and sustainable.

ComEd’s commitment to preserving habitat dates back to 1994, when the utility began planting prairie wildflowers and grasses, transforming hundreds of acres of land into native habitat. The restored prairie benefits local pollinators and other wildlife, while the plants’ longer roots aid in resilience against drought and flood, increasing carbon sequestration and stormwater detention.

In 2017, ComEd’s maps, loaded with data on utility assets and dragonfly habitat, supported an effort to relocate some of the company’s electric transmission towers. Guided by maps made with geographic information system (GIS) technology, the move was performed carefully during the insects’ dormant season, and heavy cables were prevented from striking the ground where larvae rested.

Given its pioneering conservation practices, ComEd has become a key collaborator with the Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group, reaching across industries and organizations in North America to turn rights-of-way corridors into pollinator habitat.

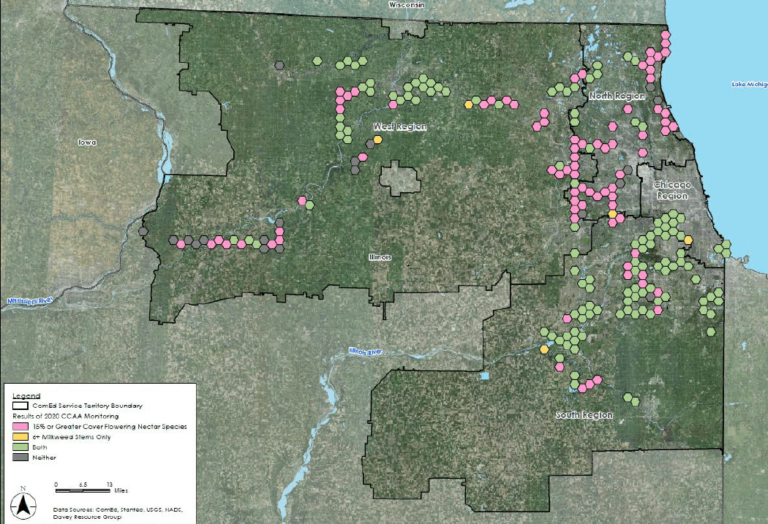

The working group teamed up with the US Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the threatened monarch butterfly species through a Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA). ComEd and more than 30 other organizations have signed the CCAA. Many of these companies share information on habitat areas they maintain to the Rights-of-Way as Habitat Geospatial Database and gains access to GIS tools for assessing sensitive areas. The data rolls into a public dashboard that tallies participants and tracks new pollinator habitat being created.

For the monarch butterfly, the key plant is milkweed. ComEd’s program engages community groups that gather seeds and the company hires contractors to plant them. More than two million milkweed seeds have been planted along rights-of-way corridors to meet ComEd’s pledge to convert more than 11,700 acres into high-value habitat for the monarch. ComEd managers use GIS to plan this work and then monitor impact on pollinators and other wildlife.

“We have standards, we have metrics, we have monitoring,” said Sara Race, principal environmental program manager at ComEd. “We use GIS to understand where there are opportunities for prairie restoration and to prioritize projects.”

It takes time and patient management practices to turn land into high-quality pollinator habitat.

At ComEd, vegetation management crews have made this work part of their ongoing efforts to keep the company’s 43,000 miles of power lines clear from trees and tall shrubs—reducing outages and fire hazards. The utility’s GIS maps track which rights-of-way corridors are transitioning to native plants and which are candidates for conversion.

“We have an annual inspection program to look at every span of transmission and make sure there’s nothing growing past our limits,” said Tom Ringhofer, manager of transmission vegetation management at ComEd.

Vegetation management teams collaborate closely with environmental restoration teams, using GIS to share data and communicate. Ringhofer says maintenance crews consult GIS maps to avoid endangered species and spot protected areas where they can’t apply herbicide. “Everything is marked in GIS so that our crews know exactly where they can and can’t go,” he said.

Ringhofer and his crews identify and clear invasive species—such as buckthorn and swamp willow—that grow too-tall thickets. Most recently, they have encountered the Bradford pear, which has a weak branch structure and typically topples within 20 years. Clearing nuisance or hazardous vegetation gives native plants and animals room to grow. An area recently cleared of buckthorn saw the return of wild indigo, wild bergamot, cup plant, and black-eyed Susan.

Lately, ComEd inspectors have been counting milkweed stems to see how many of those pollinator plants have taken hold, and then uploading their findings to the GIS. They also look for eagles’ nests, Blanding’s turtles, rusty patched bumblebees, and any other rare or endangered species.

“We’re definitely seeing more diverse habitats and species on our rights-of-ways, including turtles.” Ringhofer said.

Read more about how GIS is applied at electric utilities.

January 11, 2022 |

March 2, 2022 |

March 27, 2019 |