A lot of young people want to make a difference, but they really don't know how. If you want to do something for your community, we need people who know about engineering, architectural engineering, civil engineering, and technology.

In the early 1990s, environmental justice advocates across the US struggled to prove that marginalized communities faced disproportionate exposure to pollution and other environmental hazards. Without hard evidence, their concerns were often dismissed.

“Environmental justice was not seen as anything but the anecdotal ramblings of communities,” said Beverly Wright, the award-winning founder and executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice in New Orleans.

That changed when Professor David Padgett began supporting advocates by providing mapping and analysis with geographic information system (GIS) technology.

Through his decades-long collaboration with Wright and Robert D. Bullard—known as the father of environmental justice—Padgett established a model that transformed community experiences into scientific data that clearly shows impacts.

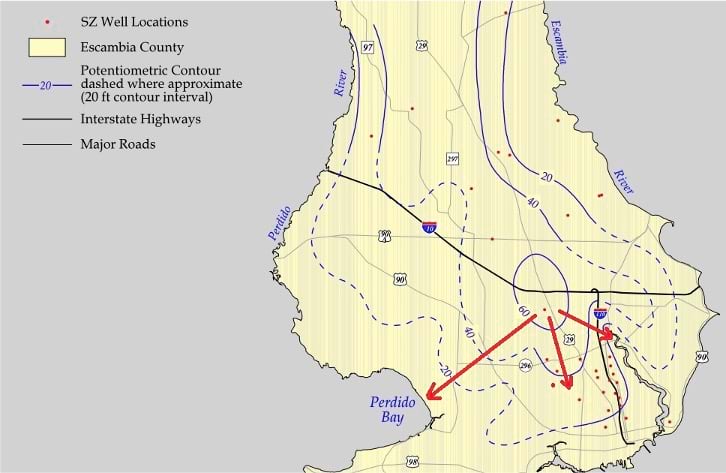

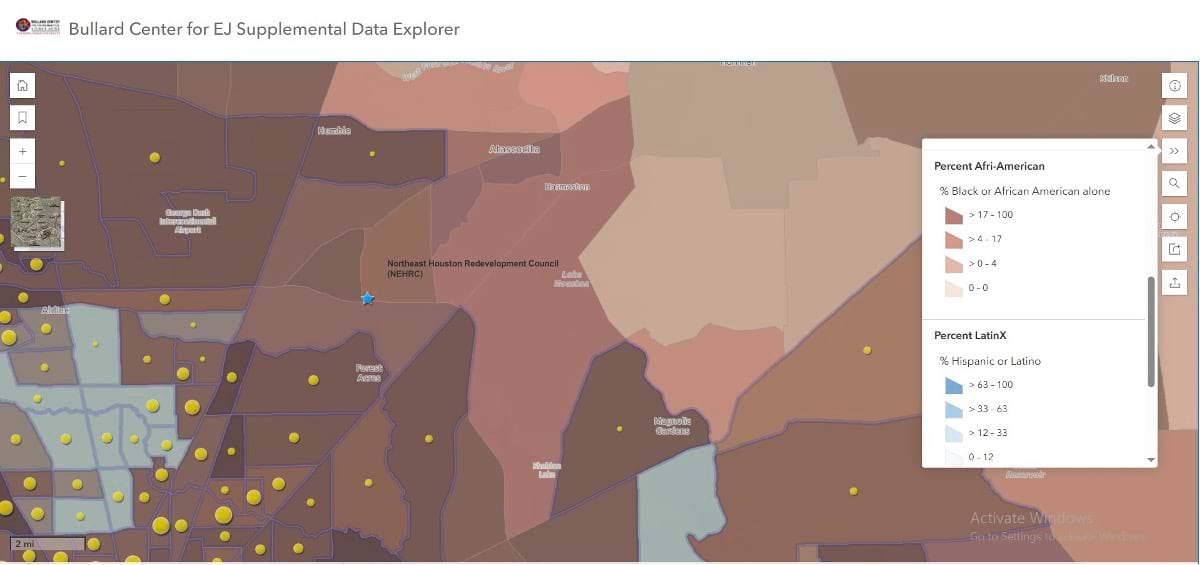

Padgett trained community advocates to create their own maps using GIS. These visual tools revealed how landfills, factories, and other polluting facilities were clustered near neighborhoods and communities of color that had higher rates of poverty. The maps documented environmental burdens including poor air quality, contaminated water, excessive flooding, and related health disparities.

GIS education and training gave community leaders the tools they needed to document compounded environmental burdens.

Armed with this data, community leaders could finally push government agencies to act.

“Being able to have access to experts like Professor Padgett, we could use GIS in many more ways than we ever conceived,” Wright said. “We could train communities to map their own problems. And all that led to the real, hard research that was needed to get government to begin protecting our communities.”

Padgett’s journey into GIS began unexpectedly. As a geography major at Western Kentucky University in the 1980s, his faculty adviser encouraged him to enroll in the school’s new GIS course–one of the first in the nation. Though Padgett dreamed of competing in Olympic track and field, he signed up.

That decision, combined with his high school studies in environmental science, launched an unexpected and pioneering career. His first job as a physical scientist at the US Bureau of Land Management put his skills to immediate use.

“I didn’t have to be trained,” Padgett said. “I already knew how to operate the software, which really jump-started my career. I was able to do a lot more a lot faster.”

While the bureau hesitated to adopt digital mapping in the 1980s, Padgett demonstrated how GIS improved efficiency and spatial analysis. He pursued advanced degrees in geography and founded the environmental consulting firm GEO-Mental in 1992, where he serves as chief consultant. Community organizations contract with him when they need data to support their work.

Padgett’s academic career led him to Tennessee State University, a historically Black college in Nashville. For 25 years, he has directed the Geographic Information Sciences Laboratory he founded there, while serving as associate professor of geography. His work earned him the American Association of Geographers Presidential Achievement Award in 2019, as well as numerous other awards (see sidebar).

Reading Bullard’s books on environmental justice inspired Padgett to expand his impact. He began attending events where Bullard and Wright were organizers or presenters, determined to connect his GIS expertise with community advocacy.

“He almost forced us to see him very quietly,” Wright said. “Everywhere you go, you see this face.”

Padgett’s timing was ideal. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 12898, requiring federal agencies to address environmental justice in their policies. Communities could get federal backing to compile evidence to support their advocacy, using GIS to carry out the work.

A lot of young people want to make a difference, but they really don't know how. If you want to do something for your community, we need people who know about engineering, architectural engineering, civil engineering, and technology.

Bullard, a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University and founding director of its Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice, was eager to mentor young professors in environmental justice. He quickly recognized the value of Padgett’s skills.

“I’m a sociologist,” Bullard said. “Sociologists and geographers and folks who do GIS, it’s a marriage made in heaven. Geographers work with data, they work with maps, and they are able to visually show in a picture what a sociologist would take a thousand words to write.”

The partnership flourished. Padgett worked with Bullard and Wright as they built the Gulf Coast Equity Consortium, which provides faculty mentors from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU) and technical support to community-based organizations addressing environmental concerns. Bullard later appointed Padgett to lead the HBCU Environmental Justice Technical Collaborative (HEJTC), empowering stakeholders through mapping and spatial analysis.

“He’s an excellent communicator and teacher,” Bullard said. “He is high-energy, and he’s very good at connecting the dots. He can do a lot of things at the same time, multitask—projects dealing with small communities or mapping something that’s on a larger scale.”

Padgett’s training transformed how communities document environmental injustices. He taught advocates to map neighborhood boundaries and use census data to reveal disparities, track the flow of contaminated water from industrial sites, document air quality with sensors, and predict flooding patterns as storms intensify.

The results were dramatic. “When we first began bringing David and GIS into the mix, the long-range goals were met in the short term,” Wright said. “My first case working with communities took 15 years. We’ve worked on very difficult cases (with Padgett), and we’ve done it in two and three years. We’ve had the science to back up the work that we were doing.”

Digital Mapping and Spatial Analysis in the Executive Office

When federal policy prioritized resilience for national security, it designated digital mapping and spatial analysis as the preferred tool for identifying vulnerable communities. In response, Padgett’s HEJTC developed the HBCU Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool (HCEJST).

The tool creates comprehensive profiles of at-risk communities by mapping multiple vulnerability factors: fewer parks, poor air quality, proximity to landfills, higher poverty rates, and elevated health risks. It also traces the historical roots—redlining, housing discrimination, and decades of disinvestment—that created these disparities.

In 2024, the HEJTC contracted with the US Environmental Protection Agency to provide technical assistance to Community Change Grant Program applicants. Now, with potential deregulation threatening environmental protections, this work has become even more critical.

“The long years of work and the acceptance of environmental justice communities, that only exists because of GIS,” Wright said. “In other words, being able to collect the data that show, yes, there are people who are disproportionately exposed. That was done with GIS maps.”

Black Americans remain especially underrepresented in earth sciences, and environmental justice still relies on relatively few advocates—a gap Padgett is determined to close.

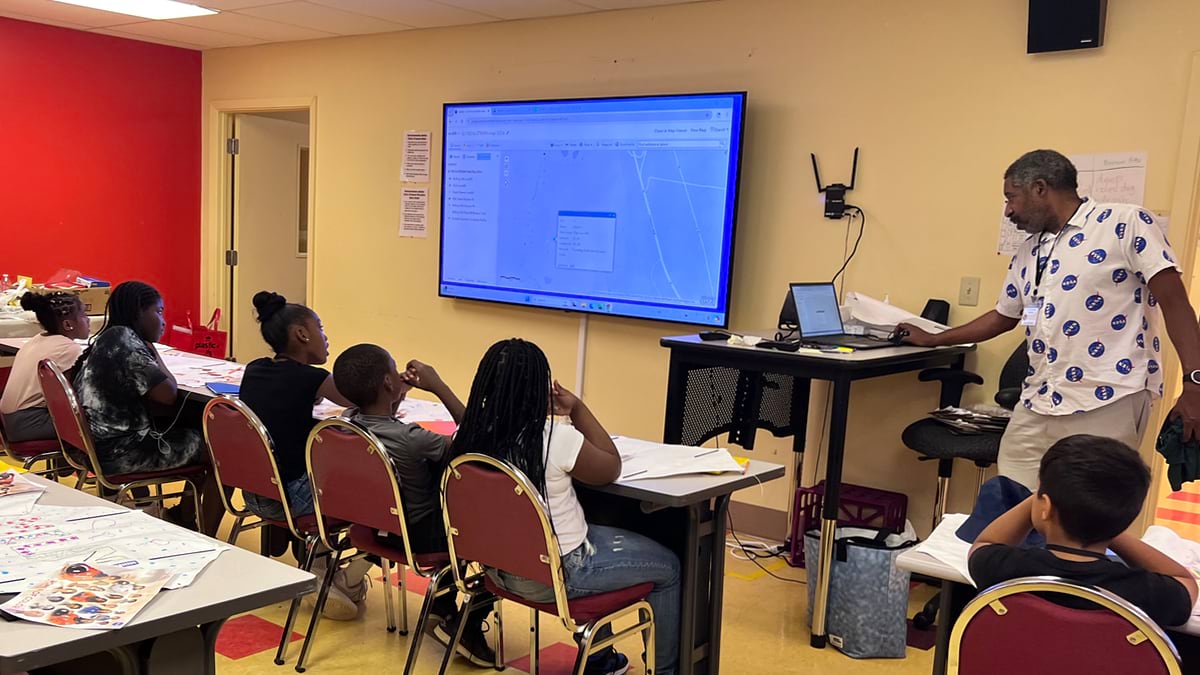

Following Bullard’s example, Padgett has introduced hundreds of students to mapping and spatial analysis with GIS through his classroom, internships, and lab opportunities. Many have landed positions at prestigious organizations, with GIS giving them a competitive edge.

Since 2001, he has trained educators through the GLOBE (Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment) program, multiplying his impact by bringing spatial sciences to classrooms nationwide.

“My goal is to close the racial achievement gap in STEM,” he said. “One way to do that is to have teachers who look like the students they are teaching. In science, there is a significantly higher chance of a child choosing a career in STEM if their teacher looks like them.”

Today, Padgett commands the same attention at conferences that he once gave to Wright and Bullard.

“He’s gotten pretty famous in this field with young professionals,” Wright said. “You should see the young people clamor around him—the way he clamored around us when he was younger.”

At 60, Padgett focuses on succession planning. He emphasizes that vulnerable communities need more professionals trained in architecture, engineering, and technology–especially GIS, which offers competitive salaries while serving community needs.

“A lot of young people want to make a difference, but they really don’t know how,” Padgett said. “If you want to do something for your community, we need people who know about engineering, architectural engineering, civil engineering, and technology.”

For Padgett, however, the true reward isn’t financial.

“The payoff is when I see people’s lives change for the better—however it is—and I had a little bit to do with that,” he said. “Young people, my friends, people that work with me, I don’t feel like I’ve won unless we all win.”

Learn more about how municipalities and environmental agencies use GIS to provide better outcomes for all people.