February 3, 2026

Patagonia stretches across jagged peaks, colossal glaciers, roaring rivers, and dense Andean rainforests at the southern tip of South America. It’s one of our planet’s last great wild places—a living mosaic of ecosystems that feel both ancient and fragile. Here, Rewilding Chile is helping nature heal from human impact and returning land and sea to the wildlife that depends on them.

“Patagonia’s biodiversity is very well conserved, but it is very threatened,” said Ingrid Espinoza, director of conservation at Rewilding Chile, an organization that works to protect the region’s ecosystems and restore habitats. “We need to know exactly what we are protecting.”

Maps are at the heart of this work. A good map can turn field data into a living guide for conservation efforts. But mapping Patagonia was once a painstaking process. Cartographers would trace the contours of mountains, rivers, and park boundaries from imagery onto transparent drafting paper. Then, the hand-drawn maps would have to be digitized.

“It was time-consuming and expensive,” said Guillermo Sapaj, director of strategy at Rewilding Chile. The process changed considerably when the organization began using digital maps and models from geographic information system (GIS) technology. “GIS gave us the ability to do this ourselves and to focus our time on conservation, not just transferring information.”

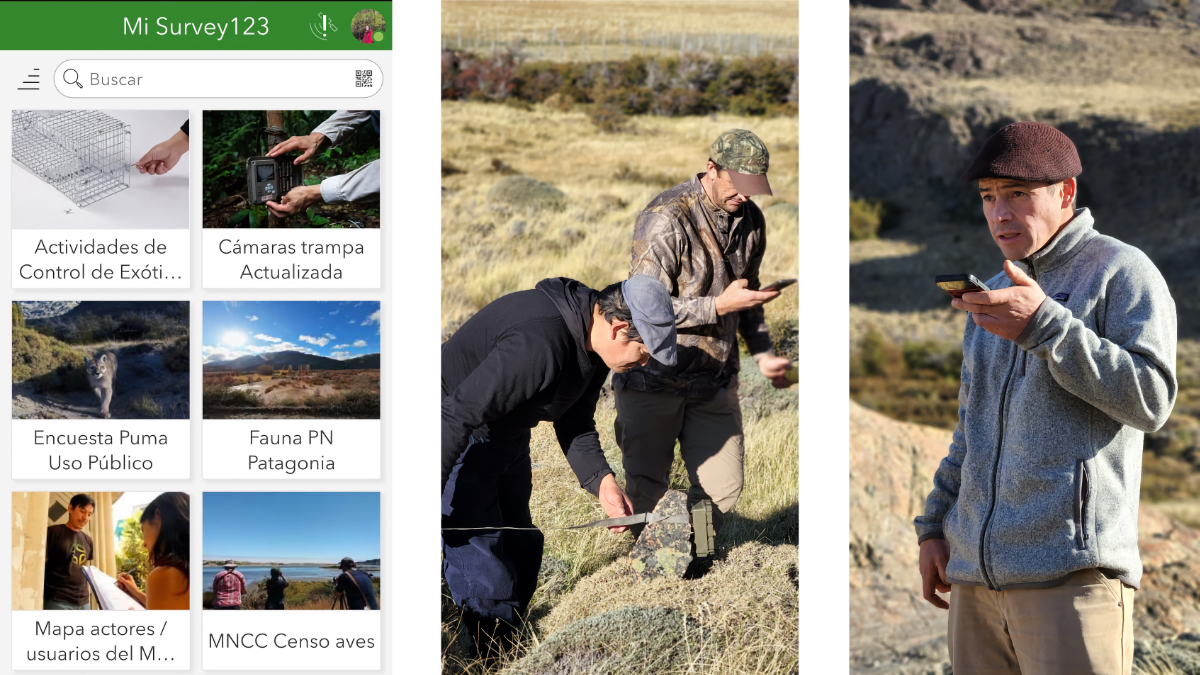

Now, rangers and field teams log sightings of native species, threats, and habitat changes directly into GIS via mobile apps. The information updates instantly, so the map reflects what’s happening in real time.

This shift has empowered the Rewilding Chile team to ask new questions: Where should restoration begin? Which areas connect critical habitats? How do we make fragmented landscapes whole again?

Patagonia’s vastness is both its strength and its vulnerability. While much of the region remains wild, it faces mounting pressures from extreme weather, invasive species, and unsustainable human practices. The threats are varied and often hard to spot until their impacts are widespread.

Free-roaming dogs wander ranch roads and park edges, acting as apex predators—chasing ground-nesting birds, pushing the endangered huemul (small South American deer) off good habitat, and spreading disease—in places like Navarino Island. In the wetlands and river flats, wild boar—introduced to the land for hunting in the early 1900s—dig up peat and muddy streams, making room for invasive weeds and altering the ecosystem.

Other threats are less visible but just as damaging. Pine plantations, planted for commercial forestry, can lead to fast-moving fires, and their seeds often spread into native forests after burns. Along creek lines, American mink—brought to Chile and Argentina for fur farming—prey on frogs, fish, and waterbirds. Red deer, imported from Europe for sport, have multiplied in the absence of native predators, browsing young forests and competing with the native huemuls for food.

Managing these threats is challenging because of the region’s complexity and scale. In the past, information about dog sightings, boar damage, mink tracks, and plantation boundaries would be scattered across notebooks and field reports. Today, GIS brings all the data together into a single, actionable view for Rewilding Chile teams, revealing hot spots, travel corridors, and pinch points. Shared maps give the team the ability to move from simply knowing there is a problem to understanding why it’s happening, what to do, and where to act first.

Comprehensive threat mapping revealed, importantly, that Patagonia’s wildlife species had become isolated from one another. The same map-based approach is reconnecting them.

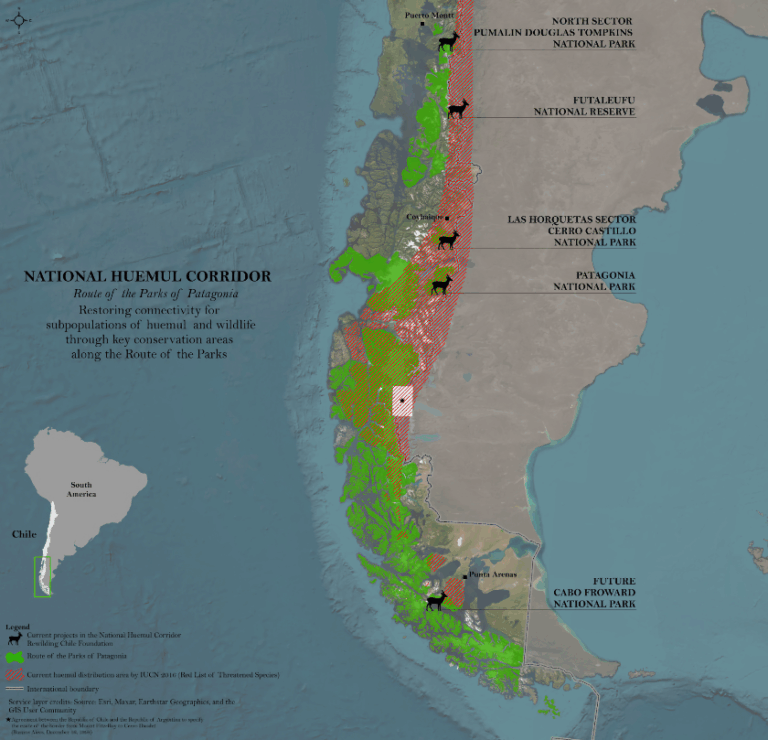

One of Rewilding Chile’s most ambitious projects, the National Huemul Corridor, is designed to help the endangered huemul. Once widespread across Chile and Argentina, huemuls now live in small groups, cut off from each other by fragmented landscapes. To address this, Rewilding Chile is creating habitat corridors—continuous stretches of protected land that connect populations. This public-private initiative aims to reduce threats, strengthen populations in key conservation areas, and establish the first rescue and rehabilitation center for this species.

“It is a connectivity problem,” Espinoza explained. “With GIS, we identify suitable habitat like slope, vegetation type, and spatial conditions, and build models that show us where huemuls thrive so they can move, feed, and breed across landscapes again.”

When GIS models flag a narrow pinch, rangers know exactly where a fence adjustment, a dog-control effort, or a small restoration project can reopen the landscape.

Patagonia also bears the repercussions of human use, especially on grasslands historically grazed by sheep and cattle. Estancia Valle Chacabuco, once one of Chile’s largest livestock operations, was reborn as Patagonia National Park through a Tompkins Conservation investment. Rewilding Chile has committed to supporting the park’s long-term restoration and monitoring.

“That landscape had been eroded for almost 100 years of heavy ranching. Today, it’s been restored into one of the most important conservation areas in South America,” Sapaj said.

As restoration progresses and the landscape recovers, the team shifts from big projects, like removing fences and planting grasses, to more detailed work. This includes reconnecting wetlands, improving trails so that they cause less impact, and making sure visitors avoid sensitive nesting areas during key times.

Mapping work across Patagonia is translating into living results. The Darwin’s rhea, a species of large flightless birds that stand about five feet tall and have a body the size of a sheep, has rebounded from a population of about 15 birds to more than 50, with Rewilding Chile’s goal of seeing that number rise to 100. The Darwin’s frog—a tiny green and brown frog with a triangular head and long pointed snout—was rediscovered in two national parks, a signal that forests remain healthy. GIS-informed corridor work continues to reveal potential huemul habitats, guiding where to focus protection and restoration.

These aren’t chance wins; they’re cause and effect. Fewer loose dogs near nesting areas means higher Darwin’s rhea chick survival. Targeted mink control in headwater streams gives the Darwin’s frog a chance to reappear where water stays cold and clean. Each time corridor modeling adds a new likely path for huemuls, field crews can either protect it or fix what’s blocking it.

“With each species, we could talk for hours,” Guillermo said, “but the pattern is the same: careful research, mapping what matters, and protecting the places that let populations recover.”

Conservation lasts when people are part of it. That’s why Rewilding Chile’s approach centers local communities as stewards and beneficiaries—most visibly through the Route of Parks, a 2,800-kilometer corridor of 17 national parks that links conservation to education, tourism, and local opportunity. The Route of Parks covers nearly a third of Chile, connecting 60 gateway communities and 91 percent of the country’s national parkland.

Rewilding Chile works alongside local and Indigenous communities, so conservation plans reflect ancestral territories, lived knowledge, and community priorities.

“Conservation won’t be sustainable if you don’t have communities that are benefiting and protecting it,” Guillermo emphasized.

Every new corridor mapped, every restored wetland monitored, and every thriving species tracked represents more than data points—it’s proof that technology and traditional knowledge can heal landscapes. With each GIS-guided decision, Rewilding Chile builds a more resilient future where Patagonia’s wild heritage can endure.

Learn more about how conservationists apply GIS to gather scientific details and safeguard biodiversity.