October 22, 2019 |

April 22, 2022

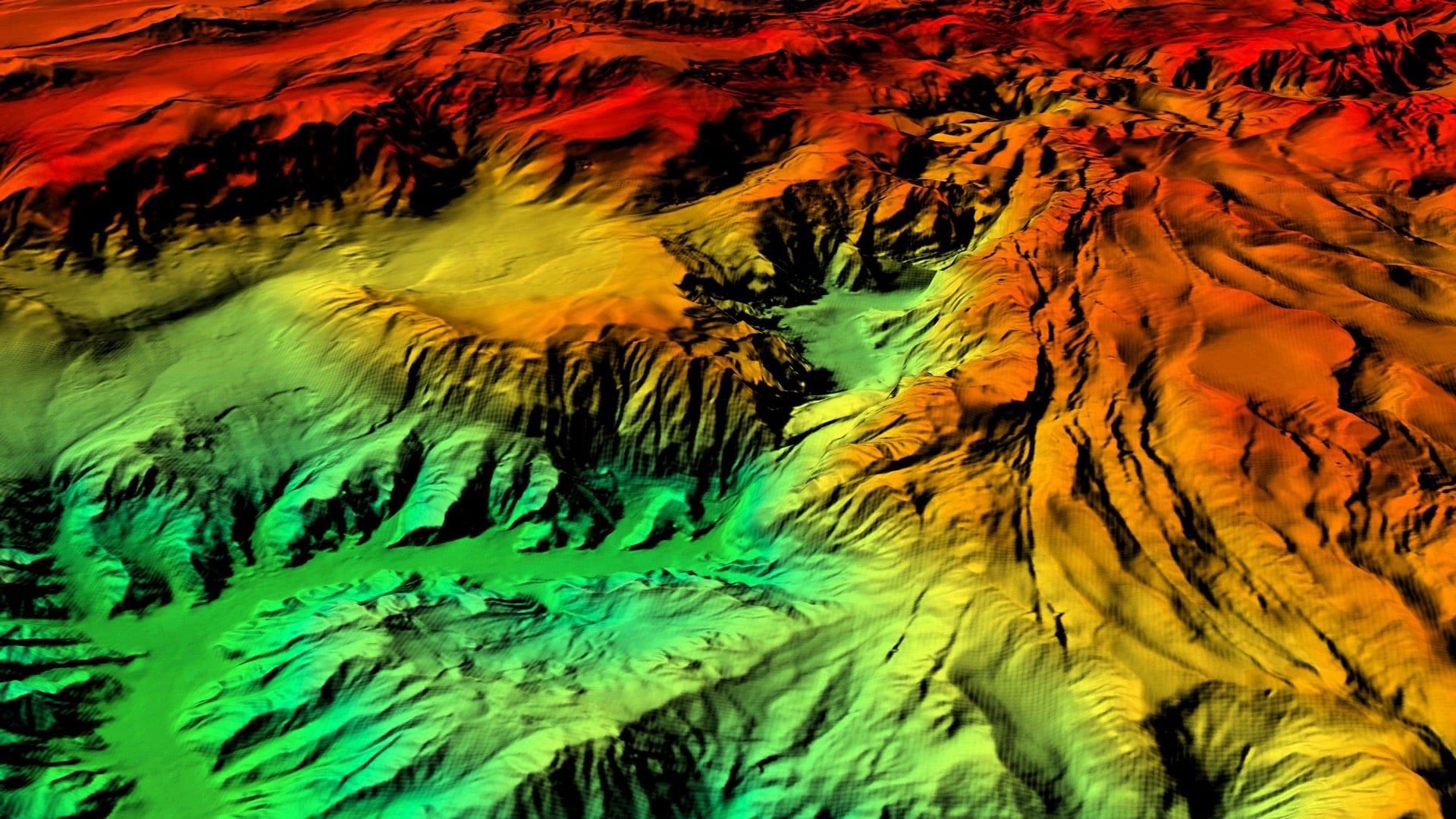

It would be nice to focus on the heartening growth of marine protected areas (MPA) on this Earth Day. However, upcoming United Nations talks on global seabed mining provide a more urgent topic.

We’ve barely finished mapping this biodiversity-rich terrain, and already there’s an effort to exploit it. Research shows that seabed disturbances heighten emissions; estimates by conservationist Enric Sala and colleagues suggest ocean trawling releases one gigaton of CO2 every year. That’s more than the global aviation industry.

Now is the time to take a stand for strong stewardship of our oceans by pausing seabed mining, at least until we can do the scientific research necessary to ensure adequate protection of the marine environment. And we must conserve well beyond the 7 percent of the global ocean that currently has some level of protection.

In July, countries that have ratified the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Law of the Sea will be discussing mining the seabed for minerals such as copper, manganese, cobalt, and nickel. The Law of the Sea stipulates that an applicant must receive an answer within two years of submitting a plan, or it can go forward under whatever rules are in place. But no rules exist yet, so countries must gather and set standards by mid-2023. And the US, by the way, has not yet ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and hence will be excluded from this process.

We simply don’t know enough about how dredging and extracting minerals from the bottom of the ocean will affect ecosystems and emissions, but the environmental costs could far outstrip the economic benefits if we don’t have a sufficient understanding of the consequences. As in all issues related to environmental health, the natural world must be a key consideration in the choices we make going forward.

I’m hopeful that more coastal states will follow Oregon and Washington in pausing deep-sea mining in state waters; that more organizations will commit to the World Wild Fund for Nature moratorium not to source any materials from the seabed; that more of my scientific colleagues will sign the international Deep-Sea Mining Science Statement calling for a pause in deep-sea mining; and that people around the world—including our GIS (geographic information systems) community—will educate themselves on this important issue.

At the moment, there is questionable demand for these minerals from the deep sea, in part because of the high costs of recovery and unknown environmental outcomes. But the interest is accelerating as the clean energy transition consumes more easily accessible resources.

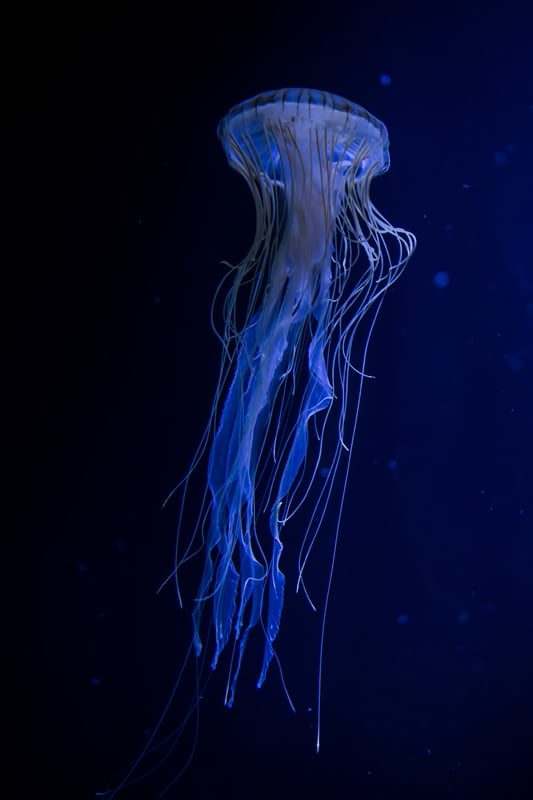

Deep-sea ecosystems are already under stress from climate change and pollution, including disruptions in oxygen levels and acidification that harms microbes, corals, and shellfish. Human and marine food chains are already experiencing impacts, and science shows the repercussions have only just begun. Acidification could also reduce the storm protection capacity of reefs, which would greatly increase the vulnerability of coasts worldwide, including my hometown of Kahului, Maui, Hawaii.

At a time when mapping is helping quantify the critical value of a healthy ocean ecosystem, we cannot continue to contribute to its illness. The ocean is the very heart of Earth’s climate system, and we need to pause and listen to the ocean, adhere to science, and develop a deeper understanding of the implications before we allow widespread extraction.

It is possible to restore vitality to degraded ocean environments and to rebuild resilience to avoid ecological tragedy. But to achieve these outcomes, we need to protect more and preserve more, because at present less than 3 percent of the ocean is fully protected in no-take zones that don’t allow any fishing, mining, drilling, or other extractive activities.

Marine protected areas provide defense against trawlers, longlines that decimate target species; oil and gas production that can pollute water and coastlines; and dumping, among other damaging activities. Research clearly demonstrates that MPAs are a simple and effective way to sustain marine biodiversity and build resilience while still supporting clean energy infrastructure. And while science has quantified the many benefits of MPAs, if you visit one, you will readily notice its vitality, which is truly breathtaking.

To tap into the power of the ocean to combat the climate crisis, more states and countries must follow California and the Biden administration’s commitment to preserve 30 percent of the ocean and land by 2030 (30 by 30). And let’s pause seabed mining before we lose the opportunity to get to know all the living things that inhabit the ocean. The ocean is vast and tempting economically, but we must move forward in sustainable ways. Further, we’ll be doing future generations a great disservice if we don’t carefully measure, map, and explore it to fully understand all that the ocean is and does for the planet.

Read stories about the use of GIS for ocean conservation. The Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative is a good source of information on deep-seabed mining.

October 22, 2019 |

May 10, 2021 |

December 5, 2019 |