The circular economy is steadily drawing the global spotlight. In November, the UK government announced £22.5 million in funding to establish circular innovation centers for industries including textiles, metals, and chemicals. In New York City, a coalition of government agencies and companies, including Cisco, H&M, and Unilever, issued a report touting the benefits of a circular economy to America’s most populous city. And an international team of researchers has proposed a framework for achieving profit with minimal environmental damage—a hallmark of the circular economy.

The groundswell of interest in reusing products and recapturing value isn’t surprising, since businesses are moving toward sustainable practices. But for companies that aim to practice a form of circularity, the trend has strengthened the case for knowing where products are during their life cycle and for deeply understanding consumer preferences in the locations a company serves.

Getting Straight on the Circular Economy

For decades, consumer demands for convenience shaped a mostly linear economy. Manufacturers used natural resources to create products, and when those products were no longer useful, owners disposed of them—typically in a landfill.

That process is expensive in many ways, including the disposal process itself. New York City spends $2.3 billion on trash disposal in a year, according to the New York Circular City Initiative’s report. Worldwide, solid waste management is projected to cost $375 billion by 2025.

From an environmental perspective, the consequences are increasingly significant, impacting air, water, and soil resources that underpin the economy. For business executives, trashing products that could be repurposed and resold violates a basic tenet of profitability: never leave value on the table—or in this case, at the dump.

By contrast, a circular economy corrals value in the system by applying several key principles: designing waste out of the system (a practice with parallels in lean manufacturing), extending the useful life of products and materials, and restoring natural systems.

Today, roughly 9 percent of the economy is circular, according to the Circularity Gap Reporting Initiative. In announcing the UK’s five new circular innovation centers, Energy Minister Kwasi Kwarteng said the UK intended to be a leader in what he called a green industrial revolution. New York City’s public-private coalition projects $11 billion in economic benefits from circularity.

Both efforts—and those of leading companies worldwide—build on a tradition of finding opportunity amid challenge and a growing interest in creating value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders.

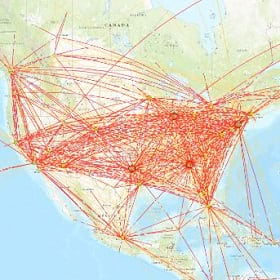

The methods that companies use to keep tabs on circular products depend on the product in question, but they are nearly always rooted in location intelligence.

Staying in Touch through the IoT

The challenge of tracking and managing the circular economy takes different forms depending on the product involved. Products connected digitally to the manufacturer can be monitored throughout their life cycle via the IoT. This includes an ever-expanding array of goods, from farm equipment and personal vehicles to home appliances, alarm systems, drones, and phones.

A sustainability manager can use smart maps generated by a geographic information system (GIS) to reveal how many products—for instance, cars or mobile phones—are in use in a given area. As numbers rise, a marketing manager could initiate a buyback campaign—geotargeted to a certain group of owners at specific phases of the ownership cycle. The rebought products can then be sold again or fed back into the production cycle as raw material for a new generation of products.

Other companies focus on minimizing environmental impacts in ways that will generate customer loyalty. Some printer companies now monitor ink levels through the IoT and automatically ship replacement ink when levels run low. The owner removes the new ink cartridge from the foil shipping envelope, inserts the used cartridge in its place, and sends it back to the manufacturer for recycling. Customers have been willing to subscribe to these services in the interest of sustainability, and companies have created more enduring relationships in the process.

These forms of circularity were once reserved for high-value, long-lived products. Now the ubiquity of low-cost IoT sensors, cloud computing, and GIS technology makes the practice both economical and on-brand for sustainability-minded companies of all stripes—even those selling IoT-connected running shoes and ski boots.

Being in the Right Location for End-of-Life Options

One of the linear economy’s most destructive products may well be single-use plastics—the bags, containers, and other implements we use once and trash, often with no recycling involved. The tendency to throw away what could be reused and revalued extends to other fast-paced consumer goods as well, including the clothes we wear.

For companies selling such products, IoT sensors might not play a significant role in creating a circular economy, but location intelligence will. Take the example of a company selling single-use coffee pods. Sustainability managers can use GIS to analyze the product’s popularity in various cities—or areas within a city—and set up recycling drop-off locations easily reached by as many customers as possible. The company can share a smart map of drop-off sites with customers via a website or mobile app.

As part of its circular initiative, New York City has taken this approach, showing residents locations where they can drop off some of the 200,000 tons of clothing they would ordinarily send to the landfill in an average year.

Businesses and local officials are helping consumers close the circle by returning goods for reuse and recycling. Manufacturers, retailers, even sanitation departments are using digital maps on websites and mobile apps to highlight more sustainable end-of-life options for products.

Using Location Intelligence to Gauge Demand

As companies move toward a more circular economy, business executives will rethink not just end-of-life options but product development as well. Some will redesign production lines to manufacture recyclable containers, while others will incorporate reused material into product design. Location intelligence could help brands retool their supply chains to minimize reliance on mined metals and opt for more reclaimed material.

To gauge what matters most to consumers, some executives will turn to a form of location intelligence known as psychographics. With GIS technology, decision-makers can locate consumer groups with a high degree of granularity. Rather than simply searching areas where coffee lovers tend to live, for instance, product planners can look for coffee drinkers who prefer green products and buy most of their groceries online.

That level of insight—seen intuitively on smart maps—can point companies toward the kind of products that will capture market share. Combined with location intelligence on supply chains and end-of-life opportunities, executives can create a game plan for a more circular economy.