Though geothermal energy currently supplies less than 1 percent of the world’s power, recent developments indicate it’s positioned to do much more.

Geothermal power plants typically use steam generated from heat trapped deep within the Earth to spin electricity-producing turbines. While they have been around for over a century they typically required conditions found in only a few geological hot spots .

Now, the geothermal market itself is heating up. Rising demand for cheap, abundant energy is converging with drilling innovations and technologies to expand the number of locations where geothermal production can succeed. A Princeton University analysis revealed that, under the right conditions, geothermal power could supply up to 20 percent of the electricity in the United States by 2050.

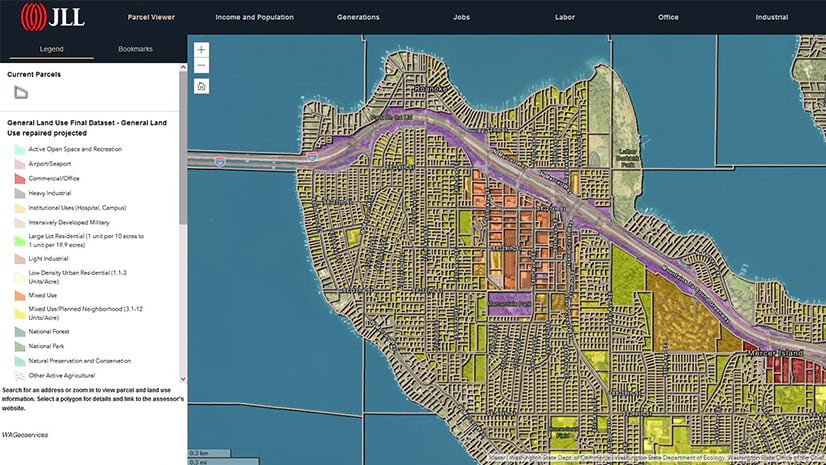

Scaling up geothermal production will require an acute sense of location awareness throughout the energy lifecycle. Across the energy sector, companies are already using maps and analysis from geographic information system (GIS) technology to

- identify the most promising sites for development.

- plan construction and infrastructure projects.

- monitor operations for safety and efficiency improvements.

Giving Heat Maps New Meaning in Geothermal Energy

Breakthroughs in geothermal technology are arriving at a time of intense global demand for new energy streams.

Europe is doubling down on renewable energy as it seeks to wean itself from Russian oil and gas. Big Tech firms are racing to plug into clean, affordable energy sources to fuel the army of data centers powering the AI revolution.

Geothermal presents an elegant solution: It produces very few carbon emissions and generates little waste—but unlike wind and solar, its wells run 24/7 and can store days’ worth of energy in underground reservoirs. Investors including Google, Bill Gates, and BP are pouring funding into geothermal startups like the US-based Fervo and Canada’s Eavor.

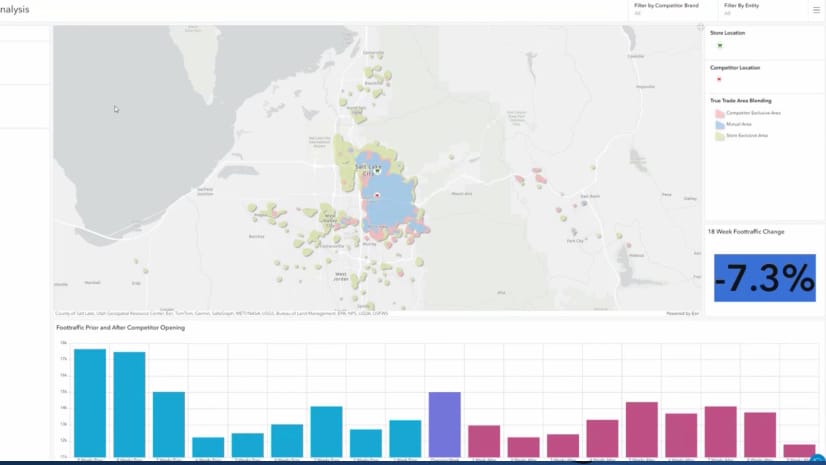

Traditionally, a significant portion of drilled wells have not been able to deliver sustained production. And with drilling and casing demanding large capital expenditures, site selection has been a high-stakes gamble. The main determinant of an energy play’s success has always been location. Yet, while drilling for oil and gas must be extremely precise, recent research by the National Renewable Energy Lab revealed that the area of geothermal potential, particularly in the US West, is much broader than previously thought (see sidebar).

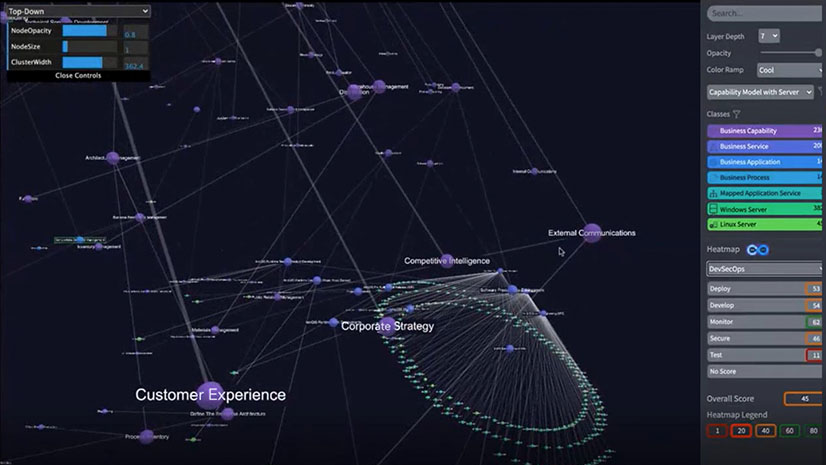

Smart maps can integrate geophysical surveys and field measurements to capture geothermal energy potential. Planners can quickly assess the suitability of new approaches like closed-loop systems that circulate water deep underground, as well as fracking techniques borrowed from the oil and gas industry.

On a data-rich map, a developer can see the subsurface areas where heat levels support energy production. Another layer could show the thickness of sedimentary columns, indicating which locations are firm enough to support drilling and closed-loop infrastructures.

To understand the infrastructure needed to bring geothermal energy online, a producer can overlay the US transmission network onto a map. Much of the best territory for geothermal in the US, for example, is in the rural west, far from major population centers. Producers will either need to site wells near customers or map the distribution networks required to transport power. In some cases, there may be opportunities to site data centers near geothermal capacity to supply a portion of base-load power requirements.

In Monitoring Wells, GIS Synthesizes Place and Performance

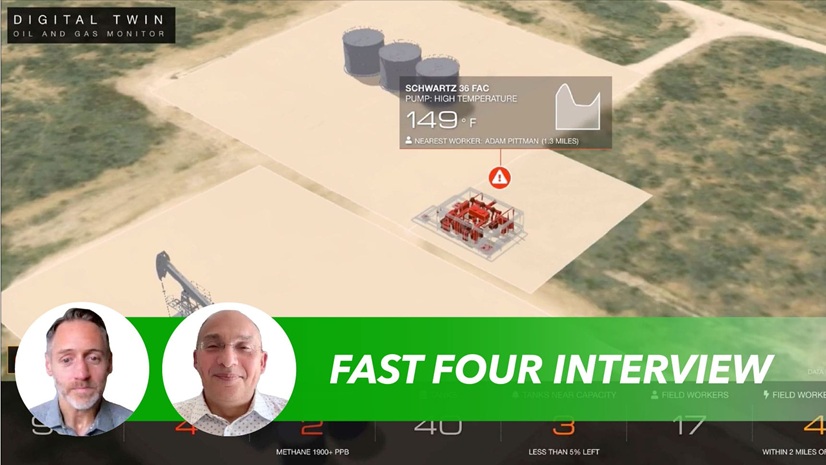

Once geothermal wells are running, GIS dashboards can be tools for operations management, combining sensor data from machinery with data on surrounding conditions to reveal trends in risk and efficiency.

Pinpointing the cause of a well’s drop in productivity, for example, might require more than numerical data. Location technology combines subsurface imaging, flow rate measurements, and environmental metrics to give managers a clear picture of well performance.

Location insights also help managers better forecast and avoid risks such as landslides triggered by wells. Overlaying weather data on a map can indicate when and where landslides might occur so teams can take preventive measures. An operations manager might also map readings of hydrogen sulfide—a poisonous byproduct of pumping hydrothermal solutions in certain situations—to ensure workers avoid dangerous areas.

For decades, GIS has powered the project life cycles of nearly every major form of energy production. As geothermal potential surges, location technology once again has a critical role to play in guiding producers to the hot spots of tomorrow’s power.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 18, 2025 |

January 6, 2026 |

September 23, 2025 |

November 24, 2025 | Multiple Authors |

July 25, 2023 |