The summer of 2020 saw nearly 20 million people take to US streets to demand racial equity. That June, as part of a multistage equity initiative, leaders at Microsoft outlined an initiative to support nonprofits making a difference in the lives of Black Americans.

The program—called the Nonprofit Tech Acceleration (NTA) for Black and African American Communities—would supply groups with cutting-edge digital technology. Partner organizations would receive donated licenses for Microsoft’s productivity apps, sales management platforms, data analysis tools, and cloud computing platform, along with free consulting on how to integrate these resources into their workflows.

Helmed by Darrell Booker, an energetic leader and former chief technology officer for a child welfare nonprofit, Microsoft’s NTA program got off to a fast start. Within four weeks of its November 2020 launch, the team had already connected with 200 organizations.

A Racial Equity Program Gets Location Savvy

NTA’s goal was to assist 1,000 nonprofits in the first year. To accomplish that and ensure a meaningful impact on racial equity, Booker needed to understand not just the organizations themselves, but the conditions of the regions they served. “As part of my work, I want to identify where the need most is,” he says.

Like many leaders at data-driven, socially conscious businesses, Booker realized the best way to find those connections was with a map.

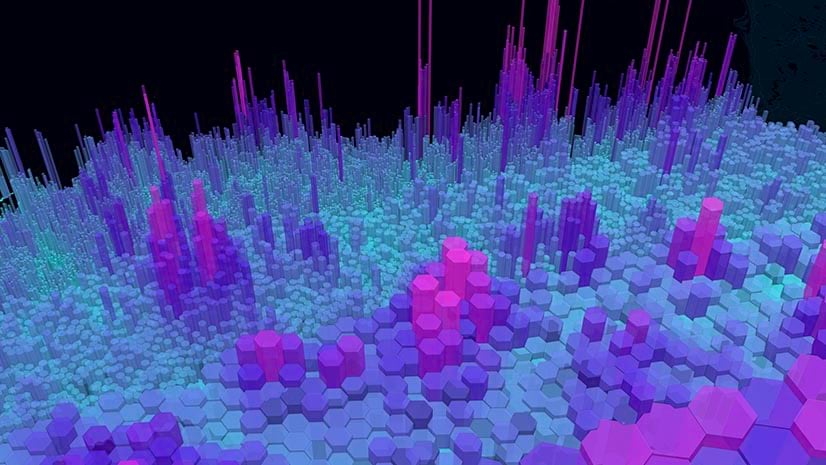

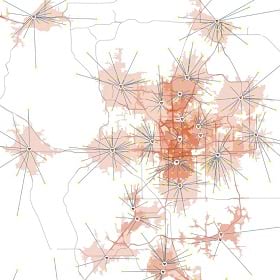

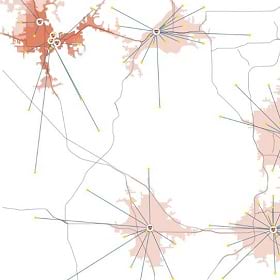

By analyzing Census Bureau data on education, housing, and poverty levels, the NTA team looked within major cities and beyond to find areas with the most profound racial disparities. That analysis yielded a dashboard called the Opportunity Scorecard, which provided location intelligence that went well beyond listing office locations on a map.

“The high-level aim was to figure out where there are synergies among nonprofits,” says Jana Alston, who helped build the Opportunity Scorecard as a research fellow for NTA. “We want to be able to say, ‘In this region, this is a hot spot, and if we can invest a lot of dollars here and do joint community activities within this spot, it could be much more impactful.’”

“[Darrell] is good at people and he’s good at really conveying a vision.”

Overcoming Systemic Disadvantages

The nonprofits that entered the NTA program—a group now numbering more than 1,500—ranged from New York’s BronxConnect, which helps at-risk youth stay out of jail, to Los Angeles’ education-focused Titus Single Parent Mentoring. Each group’s staff has personal relationships in their communities and a local understanding of how to be frontline catalysts on issues affecting Black and African American communities.

What they required, often urgently, was institutional support.

In the charity world, racial equity has been elusive. Of $2.2 billion granted to nonprofits across 25 cities between 2016 and 2018, just 1 percent went to organizations serving Black and African American communities, according to an analysis conducted by the National Committee for Responsible Philanthropy.

And Black-led nonprofits receive unrestricted funds at a 76 percent lower rate than white-led nonprofits, according to another study. This lack of support often translates into small offices operating on shoestring budgets while tackling some of the nation’s toughest challenges.

Social Impact through Digital Solutions

For Booker, the scarcity of social support networks for Black communities felt personal.

His childhood in Virginia had been happy. His father encouraged his interest in computers, letting Booker teach himself DOS commands on a brand-new Intel 286. But as an adult, Booker learned that his mother hadn’t been so fortunate. Placed in foster care at the age of two, separated from her brothers and sisters, she had experienced the failings of systems designed to support society’s most neglected members.

“So much in my past and what I experienced is really shaping how I can use technology in a different way,” Booker says now.

As his career progressed from help desk support and programming at a department of corrections to CIO at an auto parts company, he wondered how he could make a bigger social impact. When he first joined Microsoft, he advised high-profile nonprofits like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, The Salvation Army, and the American Cancer Society as they migrated their data platforms to the cloud.

Now, as the head of NTA, he was in position to improve racial equity on a national scale. He wanted to ensure that the resources Microsoft provided were going to the places where they would be most effective. To do so, he and the team had to see data in a spatial context.

“Darrell has a unique gift for connecting with nonprofits and truly understanding their mission—and uncovering their aspiration.”

Startup Energy at a Tech Behemoth

At the time of NTA’s founding, there was no established database of nonprofits serving Black communities, so the NTA team had to create one.

Booker tapped Charity Navigator for a list of the roughly 1.5 million nonprofits in the US. He used census data to identify ZIP codes where households were 60 to 100 percent Black-occupied. The nonprofits in those ZIP codes numbered 36,000.

To narrow the scope further and assign priority, Booker needed more detail on the challenges each area faced and where the best opportunities existed to build momentum for Microsoft’s racial equity program.

To help with the effort, he brought on Alston, who at the time was pursuing her master’s degree in policy management at Georgetown University. Though she didn’t have a deep background in tech, Alston found Booker’s passion and vision for the NTA program infectious.

“It was like the energy you expect from a startup, but within this behemoth that is Microsoft,” she says. “It’s kind of like the best of both worlds because you have all the resources and support system, but you have this new, raw energy and potential.”

A Tapestry of Neighborhoods

In developing what would become the Opportunity Scorecard, Alston took inspiration from a dashboard created by Microsoft’s Airband initiative, dedicated to expanding broadband access and adoption among at least 3 million rural unserved people, as well as in eight US cities where Black and African American households lack affordable internet access.

“My work in broadband access and digital equity often intersects with NTA because our focus communities overlap,” says Aubrey Coleman, a business program manager for the Airband initiative. A few years ago, Airband released data maps showing that 120.4 million people in the US do not use the internet at broadband speeds—more than a third of the nation’s population. The Airband team shared its broadband maps, methodologies, and other useful data points with Alston, while Booker, who frequently meets with community leaders, shared contacts and on-the-ground intelligence.

“Darrell has taught me that each community across the country is different and requires a different approach,” Coleman says. “We must use both quantitative and qualitative data to meet communities’ needs. Each is unique in its philosophies, how it operates, which stakeholders have credibility in the community, and in its expectations for partnerships.”

To illustrate those differences, Alston used color coding and the clear outlines of metropolitan statistical areas on maps showing how seven key metrics, including low rates of four-year college degrees, homeownership, income, and access to high-speed internet were compounding negative effects on communities.

“We wanted it to be something that an outsider, who has no experience or knowledge of the program, could look at and very clearly understand that these 10 or 15 or 20 regions are the special ones,” Alston explains.

With this knowledge, NTA team members could focus on nonprofits in those areas and reach out to assess each one’s technological needs.

By displaying information in a geographic context, Booker and team could cross-reference nonprofits across the country with demographic data that illuminated underserved Black populations—and the places Microsoft could help most.

Digital Transformation at the Community Level

Well before the end of NTA’s first year in action, it had already connected with 1,000 organizations. But as Booker reviewed the loose distribution of nonprofits on the map, he began weighing how to synthesize efforts among the organizations to deepen their impacts.

“That was when I started to change my mindset and say, ‘You know what? I have to look at these on a community level,’” Booker says. “I want to be able to say, ‘I have digitally transformed 80 percent of the nonprofits in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.’”

By the time Alston’s fellowship ended, her location analysis had yielded a list of 20 primary areas where NTA’s efforts could produce the most impact on racial equity. That led Booker and the team to focus on pockets of the country outside well-known cities, like northeast North Carolina, southwest Georgia, and one cluster of ZIP codes on the border of Indiana and Michigan.

Building for the Future

For Booker, location awareness will continue to guide how he and Microsoft serve the communities identified by NTA. He’s increasingly turning his attention to groups that coordinate efforts among community organizations, and he’s using spatial understanding to fine-tune outreach and program marketing.

As he achieves NTA’s near-term goals, Booker is also thinking 5 or 10 years ahead. By tracking the success of individual nonprofits along with metrics on their communities, he hopes the combined effects of NTA’s partners will begin showing up in improved measures of racial equity, including increased education levels and decreased poverty in NTA’s areas of focus.

“My mantra is ‘build for the future, not the now,’” Booker says.