While we have long been accustomed to tracking the dynamic data that determines the weather, we now find ourselves at the dawn of a new era of forecasting. Call it human weather. In my work with some of the largest and most innovative companies in the Bay Area and beyond, I’ve seen the tremendous promise that human weather holds.

“I move; therefore I am,” observed Haruki Murakami, the renowned Japanese writer. Organizations intuitively understand the value they can gain from knowing more about the movements of established and potential customers, but most are simply unaware of how much insight into these movements is now available.

Today, Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled devices have created legions of human data sources, whose signals can be understood in much the same way that we understand traditional weather data. Just as businesses benefit from traditional weather information—by routing supplies around natural disasters, positioning field crews to mend damaged infrastructure, and even predicting how a heat wave might affect sales—a broad range of business activities can benefit from data on human weather.

Companies are gaining competitive advantage from the data exhaust generated by mobile applications that use location awareness.

The term human weather was coined by Myles Sutherland, founder of consulting firm One Degree North and former head of Esri’s startup partner program. It refers to a real-time (or near real-time), high-volume data stream about human activity. It is principally about location—how and where people move— but also encompasses behavioral components. Imagine being able to track the patterns and impact of human activity like a meteorologist tracks weather fronts. The technology to do this exists, and pioneering companies are beginning to use it to observe, document, and predict consumer behavior, even as they take steps to ensure the privacy of individuals.

Early Weather Watchers

If backyard and mountaintop weather stations are the sources of data for our seven-day forecasts, where do we find the data to understand human weather? The three principal sources of insight are mobile devices, financial transactions, and vehicle telematics.

For example, companies are learning much from the location exhaust generated by mobile applications that use location awareness. Social media, ridesharing, navigation, and dating apps know the location of users that have opted in to this kind of sharing. Third-party providers aggregate and anonymize that information, then serve it out as geographic, or spatial, data so companies can do things like call up storefront locations and see what retail traffic looks like at their own locations and those of competitors, comparing today’s traffic to the previous week’s or last month’s.

Knowing the ebb and flow of traffic can tell a company that an upstart competitor is beginning to gain traction with passersby, or that its own out-of-home advertising isn’t drawing as much traffic as hoped. Airports are even beginning to adjust the cost of retail space based on the flow of foot traffic through the terminals. High-traffic areas can command premium rents.

In this way, the data generated through our smart devices—that is, the location exhaust of our mobile applications—becomes a valuable resource for business insight.

On the transaction side, credit card providers and financial data aggregators are also using human weather techniques. Consider a person who uses multiple credit cards. While the data from the card transactions is anonymized, the associations between the accounts are still visible, so a marketer can use that data to see the full customer journey—the latitude-longitude of each transaction across a period of time. Understanding purchases across product categories, services, and experiences can help companies tailor messages to the right buyers and increase marketing ROI.

In the realm of vehicle telematics and traffic modeling, community-based traffic and navigation applications like Waze and INRIX are a prime source of insight into human weather. They collect data on people maneuvering from point A to point B, and the most prominent apps have millions of users, providing insight into human movement on a massive scale.

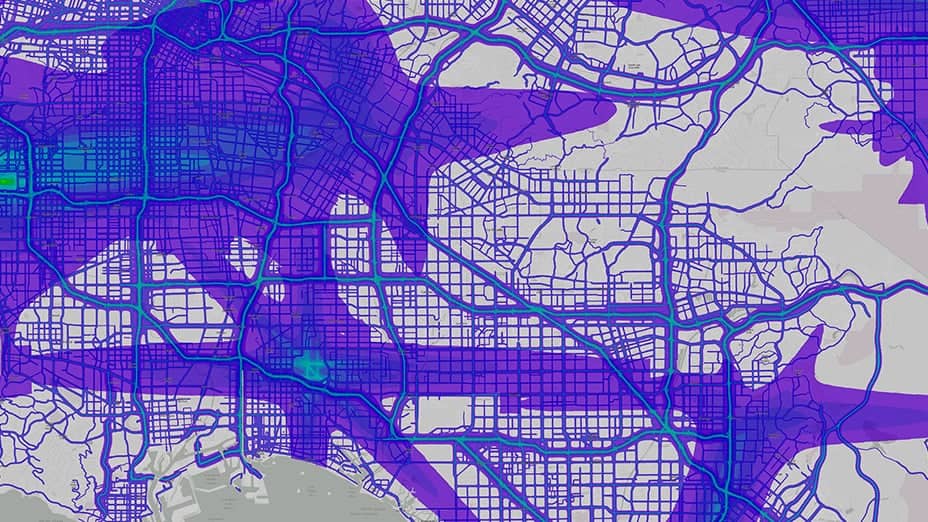

Cities, for instance, are sharing information—roadwork plans on a major bridge, or street shutdowns due to an upcoming marathon—with these application providers. The applications’ algorithms account for these events and effectively route people around them. The application providers love that data because it enriches and improves their applications; in return, the cities learn in real time about conditions in their area—cars on the shoulder of the road, road debris, and more. Dispatchers at the cities’ departments of transportation can visualize that insight on maps served by geographic information system (GIS) technology, and understand spatial patterns and movement within the municipality, deploying responders accordingly.

Companies and municipalities are experimenting with human weather initiatives with increasing frequency. In these early days, it’s helpful to think of these experiments on a maturity curve. On the left side of the curve, organizations are comparing human weather data to their own data, looking for correlations. On the right side of the curve, companies are using this data for predictive intelligence, anticipating with far greater accuracy things like how many people will visit their store next weekend, how sales will rise during a holiday weekend, and which competitors are beginning to gain customers.

The concept is a powerful one, and we can expect it to be embraced across a broad range of commercial and government sectors. Three have emerged as early adopters:

- Retail site selection and market planning

Retail companies have been among the first in the commercial sector to adopt human weather techniques. They use the data to make better real estate decisions and to market products and services with a more personalized touch. - Civic development

Human weather is being used to build smart cities by making better transportation decisions (where to locate transit stops or route new transit lines) and recreation choices (where to build parks and facilities based on human movement), and by conducting better event planning and real-time management. - Public safety

Police departments and other agencies are interested in human movement on the macro and micro levels (i.e., activity across an entire city or on a specific block). They’re also parsing transactional data to assess risk and allocate public safety resources based on where people are, where they go, and how they move through municipalities.

Gaining Optimal Insight from Human Weather

The Internet of Things is the connective fiber in an increasingly connected commercial and industrial ecosystem, offering real-time insight throughout the economy. Consider the billions of sensors embedded in airplanes, manufacturing equipment, roadways, office buildings, and everywhere in between, and the rich stream of information they provide. In much the same way, the IoT is the sensory system behind human weather, in that technology has moved to the center of our lives, essentially creating human sensors.

The cell phones, fitness trackers, and other IoT-connected devices we carry around produce a profound variety and volume of data about our behavior—how we bank, work, shop, work out, and more—all tied to a specific place and time.

At a recent conference on the development of smart communities, Stephen Goldsmith, professor at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and former mayor of Indianapolis, made the following observation: “Data is everywhere and can be collected from everywhere, including from individuals walking around with cell phones. With this massive amount of data, we need context; and GIS is an organizing context for data.”

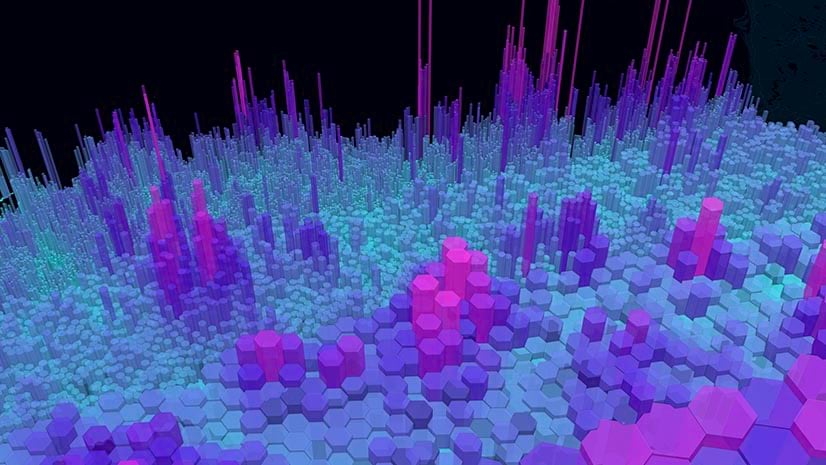

A geographic information system leverages maps to help organizations understand the spatial associations within this massive collection of data. That might mean plotting out the longitude and latitude of where people are when they request a mobile ad, or swipe a credit card, or move between locations. Companies can add layers to that information, just as one might place an acetate layer over a map, so that more detailed insight can be gained as data sets are combined. This technique enables new kinds of observations, ranging from seeing things like traffic hot spots or cold spots, to anomalies that simple charts don’t uncover.

In the retail sector, for instance, a company looking to chart human weather might draw a boundary around its store, then define a rule that if a device dwells there for a predefined period, some action results. Marketers could send a push notification about a time-sensitive offer, or a back-end analytic system could register the visit and add a benefit to the customer’s loyalty program account.

Just as weather data is being embedded in business logic, I believe we will see human weather data enabled in products and services to provide a standard way of making decisions.

In addition to taking actions based on individual movements, the retailer might roll up the data to create what amounts to a local forecast. The patterns of human weather visible in the data can aid in predicting store traffic and sales, allowing the retailer to adjust staff and stock the store accordingly.

A bank can analyze another form of human weather—origin/destination data—to determine the right location for a new branch. Origin/destination data shows the home zip code connected to purchases in various sections of the city, revealing where people travel to eat, drop off dry-cleaning, and more.

With modern GIS technology, bank planners can see the demographic and psychographic characteristics of those zip codes, cross-reference those with a targeted customer profile, and choose a branch location that serves the highest concentration of those ideal customers.

These are two cases among many. As the benefits of understanding human weather grow, companies in many industries will find ways to augment data, workflows, and products or services with human weather information.

Broadening the Outlook

This information simply wasn’t available in years past; but now that we’re all carrying around little computers in our pockets, our weather patterns are becoming clear. What are the implications?

In the same way that executives have questioned the value of their traditional databases, they now must assess the worth of human weather data. Some will worry that another data stream will add to the noise within the company. But forward-thinking executives are already reaping benefits from the above scenarios and other uses of human weather, As a recent Forbes article noted, “the McKinsey Global Institute indicate[s] that data-driven organizations are 23 times more likely to acquire customers, six times as likely to retain those customers, and 19 times as likely to be profitable as a result.”

I believe we will see organizations begin to build these dynamic datasets into their products and services to provide a standard way of making decisions. At first, they may not push these decisions to an individual using an application. Instead, the application itself will make decisions based on human weather conditions.

One example might be a ride-sharing app that automatically routes drivers to the vicinity of a concert venue because it receives an input indicating that a large number of mobile devices are in use at the event. Similarly, a manufacturer’s supply chain management system might automatically re-allocate products to a local distribution center based on a spike in purchases at nearby stores.

This is how human weather will begin to permeate the business world.

To make better business decisions, executives must leverage not just the data they manage in-house but also additional sources of insight into human weather, including from the sensors around them—cell phone movements, point-of-sale transactions, even computer-vision within cameras.