August 31, 2021 |

November 29, 2022

Each summer, Melanie Smith notices the small, brown birds that take up residence in her backyard in Talkeetna, Alaska. As the program director for the Bird Migration Explorer, a trained ornithologist, and a lifelong birder, she knows that these creatures are Swainson’s thrushes. But just recently, she learned that they migrate from as far as Argentina in the spring to spend the summer nesting near her home.

“When you see birds in your backyard or out in your local park, it feels like they’re your birds,” Smith said. “But they’re many peoples’ birds. They go from community to community, and a lot of them are spending three-quarters of their time outside the United States.”

Over the past four years, Smith and her colleagues at the National Audubon Society have been working with founding partners and hundreds of researchers to tell the complex story of bird migration using geographic information system (GIS) technology. The process required aggregating research data from hundreds of institutions and designing an accessible, beautiful, and dynamic platform.

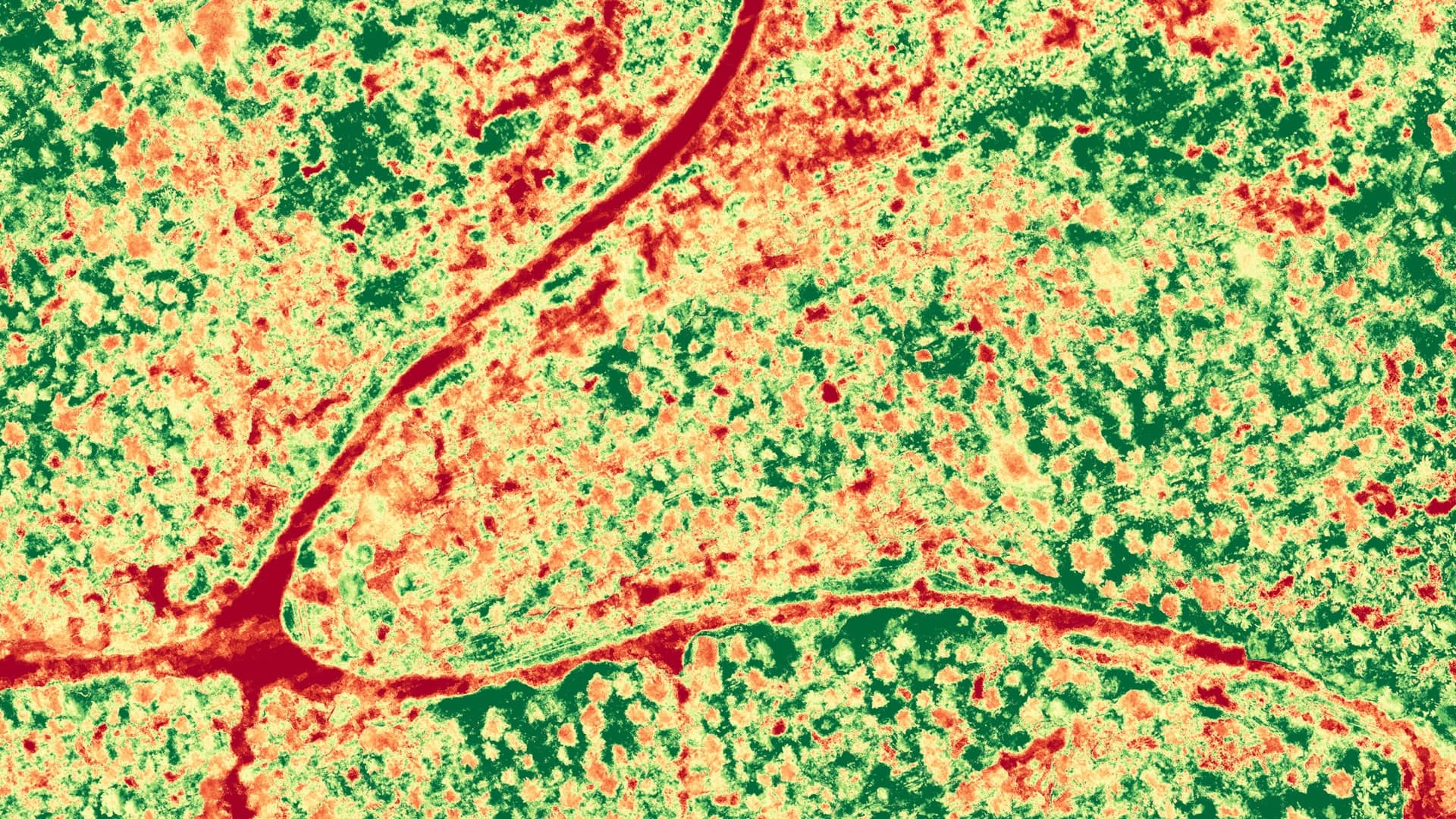

Utilizing millions of location data points, the newly launched Bird Migration Explorer allows users to visualize on maps of the incredible annual journeys made by over 450 bird species across the hemisphere. The free, interactive digital platform—available in English and Spanish on desktops and tablets—connects birds to locations across the Americas and reveals the extraordinary challenges they face in flight. Such insight is invaluable and timely: In the past 50 years, we’ve lost more than 2.5 billion migratory birds from North America.

“Birds are important ecological indicators,” Smith said. “They tell us about the health of the environment because what birds need and what humans need are very similar: clean air, clean water, open space, access to food, and shelter. When we see their populations declining, we have to wonder what’s causing that and how we can remedy it.”

In late 2018, Audubon established the Migratory Bird Initiative and its focus was multifaceted: identify places that migratory birds need and protect the ones that matter most, reduce threats to birds, and engage people from diverse communities in the joy of birds and the wonder of migration. With this mission in mind, Smith and her team asked: How can we use data to drive conservation efforts? By mapping when and where birds face challenges, such as suburban development or climate change, Audubon can investigate root causes of decline, and engage with communities and local organizations to reverse the decline and preserve biodiversity.

Presented using three types of maps—species, locations, and conservation challenges—the Explorer combines bird banding, tracking, abundance, and genetic data with geography. Intricate illustrations of each species, a custom basemap built by Esri, and well-crafted storytelling help the Explorer appeal to multiple audiences, from conservationists and advocates to birders and the casually curious.

The platform’s eye-catching design is fueled by troves of data that were identified, processed, and published to ArcGIS Online. Each of the partners listed on the Explorer homepage provided aggregations of migration science. Tracking data was the exception, because individual scientists owned that information. And to secure it, Smith and her team contacted each one of them.

The data was then combined in Movebank, an online platform that helps researchers manage, share, and analyze animal-tracking information. In total, 283 institutions have contributed to the Bird Migration Explorer.

Smith worked with staff members across Audubon, contractors, and partner organizations to ensure that the bird migration science was accurately and meaningfully depicted. Audubon director of enterprise GIS Connor Bailey facilitated the integration of cutting-edge GIS capabilities with the project’s broader vision.

“Early on, we had to find the right technology and work closely with Esri to make sure that our underlying infrastructure could handle the immense amount of information we were bringing together,” Bailey said.

Bailey and his team partnered with Esri partner Blue Raster—a company that creates an array of dynamic web and mapping solutions—and other organizations to build a fully functional application. With a two-decade-long career in enterprise GIS for nonprofit organizations and conservation initiatives, Bailey said that the Bird Migration Explorer is the largest project he’s worked on. Over 100 people were involved in the development stage alone.

The Explorer launched in September, but Smith, Bailey, and the rest of the Audubon team know their work isn’t finished. “This is an ongoing project that will continue to live,” Bailey said. “We’re looking forward to building out more capabilities and processes for long-term maintenance, because this is intended to be a living, breathing, interactive atlas and repository where all of this migration information can come together in one place.”

GIS technology is integral to conservation initiatives because it allows scientists to make informed decisions that will affect biodiversity and the planet.

“Each of the datasets provides a different knowledge system,” Smith said. “By combining them, it doesn’t necessarily mean we have all the answers, but it does mean we have the most complete picture, and we will use that to inform smart conservation.”

Smith is quick to note that the 458 species included in the Bird Migration Explorer account for less than 5 percent of all bird species in the world. In the future, she looks forward to adding datasets and more species. A simplified experience for mobile users is in the works as well.

The mobile version of the Explorer will join other portable birding resources, such as Audubon’s Bird Guide app—which contains the organization’s complete Field Guide to Birds—and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird app. These in-the-field resources give naturalists, birders, and first-time explorers access to authoritative data that make the birding experience more rewarding and enlightening.

Even though the Explorer is just one piece of Audubon’s conservation strategy, Smith and Bailey anticipate finding more ways to use a geographic approach in their work. “GIS allows us to visualize and understand problems we face from a geographic perspective,” Bailey said. “That’s important because we need to be able to understand our landscape in order to actually make changes that benefit humans, biodiversity, and birds.”

Learn more about how GIS helps preserve biodiversity and achieve sustainable conservation.

August 31, 2021 |

November 21, 2022 |

August 17, 2021 |