July 12, 2022 | Multiple Authors |

September 13, 2022

Despite being close to the growing city of Santa Barbara, the land around Point Conception, California, is wild enough that mountain lions and bears hunt on the beach. Biologists say it feels like turning back the clock.

Archaeological work has revealed 9,000 years of continuous human occupancy, including sacred sites of the Chumash people. Indigenous peoples such as the Chumash gathered natural resources from both the ocean and coastal mountains and stewarded the area for thousands of years. In more recent times, this land somehow escaped the imprint of infrastructure, although it’s had some near misses. A convergence of factors have stood in the way of development, including the land’s rugged topography, a history of livestock ranching, the inland routing of the iconic coastal Highway 1, and high security for neighboring Vandenberg Space Force Base.

Point Conception sits where the Southern California coastline bends north, and so marks a major ecological transition between northern and southern ecoregions. The area is a great example of an ecotone, with flora and fauna from both areas that intermix and create an abundance of species not found in other places. In California, the most biodiverse state, the Point Conception region is among the nation’s most biodiverse places.

Five years ago, a nearly 25,000-acre property at the point became available. The site, formerly the Cojo-Jalama Ranches, had been slated for development. However, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) was able to purchase the property, backed by a donation from Esri founders Jack and Laura Dangermond, putting this land on the path of preservation.

Some of the very first maps TNC created decades ago using geographic information system (GIS) technology marked this place as a priority for protection. Since then, the organization has purchased and conserved 125 million acres of land in 70 countries. Now TNC has established the Point Conception Institute to harness the power of open science to tackle urgent challenges related to climate change and biodiversity loss. The institute fosters diverse research collaborations with data stewardship and sharing, and applies innovative technical and geospatial solutions that use the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve as a living laboratory.

The idea of the institute came from the need to explore, measure, study, and learn from this last coastal wilderness in California. “There’s a real opportunity to develop a new model for conservation, using open science to establish legacy datasets that can be brought together with other data streams to create a true interdisciplinary collaborative effort,” said Mark Reynolds, director of the Point Conception Institute.

While TNC was already using GIS widely, the donation by the Dangermonds cemented a triumvirate of partners. Nearby University of California, Santa Barbara, already had a Jack and Laura Dangermond endowed chair in geography with world-leading experts in geographic information science, and now it has an endowed chair in conservation science with an emphasis on leading innovative research projects on the Dangermond Preserve.

The aim of these partners, including solution engineers from Esri, is to gather the many dimensions of Point Conception quickly, because the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss are quickening.

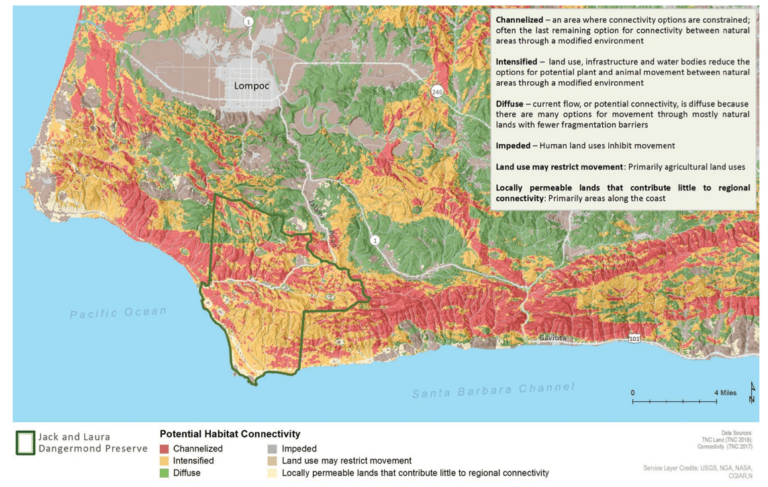

In the face of climate change, ecotones are particularly important because they represent the front lines of habitat ranges that are constantly expanding or contracting. Ever in flux, the existence of infrastructure such as oil fields or subdivisions can prevent species from migrating to more favorable habitats and increases the risk of population decline or extinction. Without these barriers, Point Conception is poised to preserve species that struggle elsewhere.

Scientists have already compiled 90 layers of GIS data to capture details about the Dangermond Preserve including its archaeology, wildlife, and vegetation. These layers create the foundation of a digital twin of the landscape that lives within GIS. Digital twins can be instrumental in helping land managers inventory existing conditions, identify relationships between the conditions that define ecological systems, and simulate landscape processes.

With the digital twin of the Dangermond Preserve, the institute is out to understand the landscape; visualize it; and forecast what it will look like in the future, given the human and natural impacts the area experiences. The aim is to not just inform biodiversity science but also understand the social, cultural, economic, environmental, and other dimensions of the place.

“We’re really in a race,” Reynolds said. “All of this needs to be assimilated faster.”

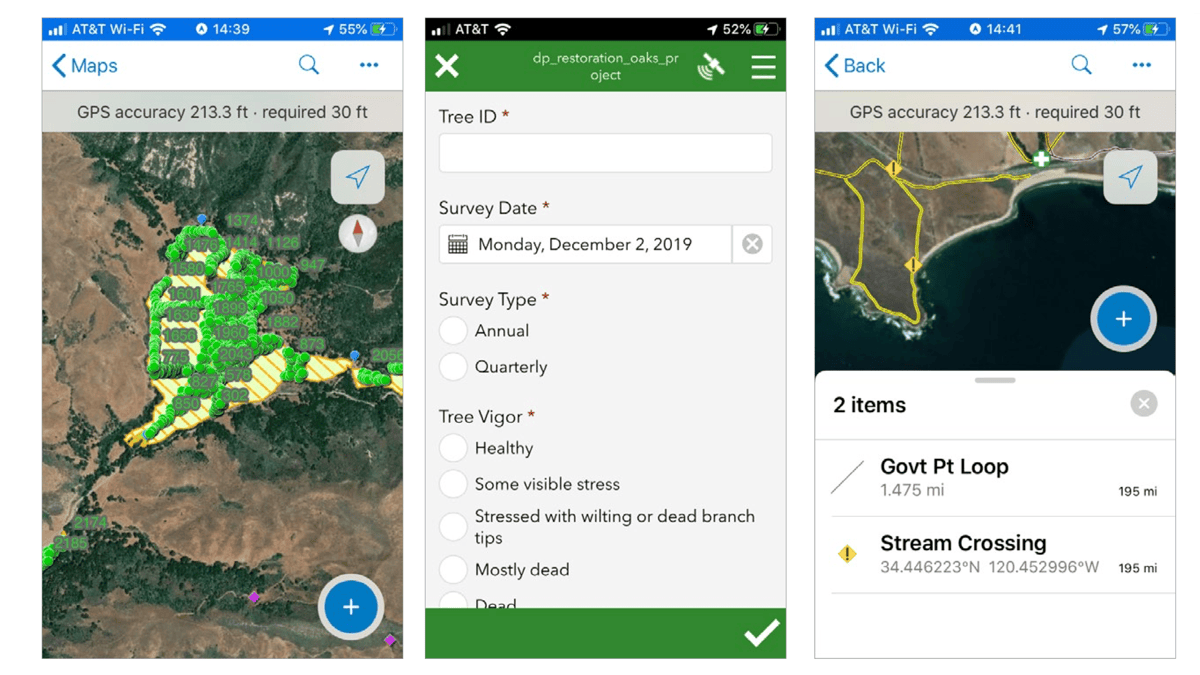

TNC’s first priority was to conduct landscape-scale inventories and create management plans for grazing, fire, roads, invasive species, and other necessary factors. On the science side, TNC is working with a large number of research partners wielding sensors, handheld devices, drones, and more of the latest tech to gather information quickly to be visualized and analyzed.

Reynolds, the lead scientist at the preserve, applies his experience as a vertebrate biologist and from his 21 years of work in California on migratory bird and salmon conservation, oak woodlands restoration, and other projects. At the Dangermond Preserve, he’s in charge of a research enterprise that’s focused on biodiversity preservation, conservation action in a changing world, and climate change adaptation.

Kelly Easterday leads conservation technology at the institute, working closely with Reynolds to apply GIS to streamline operations, facilitate research, and record knowledge about the preserve.

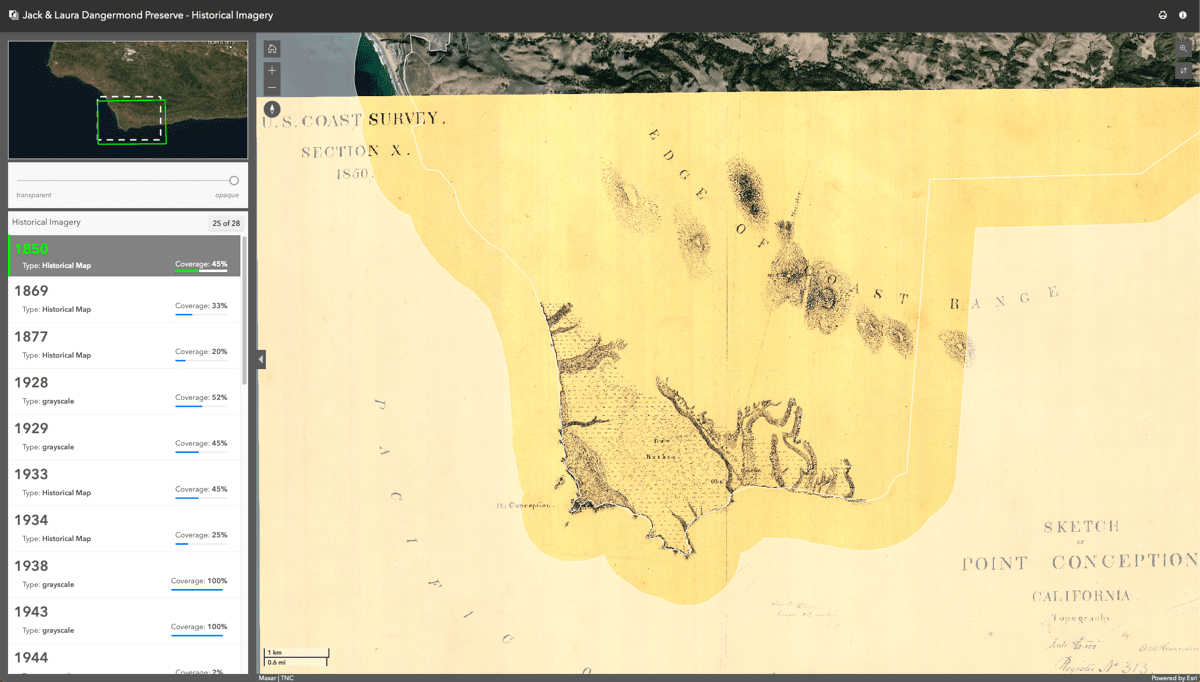

During her doctoral work, Easterday paired historical vegetation maps with modern forest inventories to describe changes across California forests and woodlands. In similar work, documenting the preserve’s historical ecology—to know how the preserve has changed over time—has been an early priority.

A good deal of the work on the Dangermond Preserve focuses on restoring habitat, combating invasive species, and taking action to improve habitats. This work is documented in the integrated resources management plan with maps of where restoration needs to take place, along with details of the methods being applied.

Leveraging the digital twin to advance their research on the preserve, scientists are analyzing the natural processes and ecosystem services of the place. Scientists use apps for field data collection to add their knowledge to the digital twin, and then apply spatial analytics to derive understanding.

The work also involves big data analysis, with the aid of artificial intelligence, to decode troves of camera trap and drone images and other large volumes of data from sensors that record measurements from all over the site.

Freshwater at the reserve is very limited, and scientific work to understand the groundwater provides a good example of the digital twin approach being taken. The preserve encompasses an entire watershed, from coastal shallows to the heights of the Santa Ynez Mountains. To learn more about the watershed, hydrologists turned 22 groundwater wells into a sensing network to monitor groundwater movement and recharge rates. They added sensors along 50 miles of streams to reveal surface flows and temperatures. Data from the wells and stream gauges pipes into the digital twin to monitor the vital signs critical to the health of the landscape.

“The sensors and research partners give us an incredible opportunity to understand how a fractured rock coastal watershed operates,” Reynolds said. The mix of sensors and GIS provides near real-time readings and informs long-range planning. The knowledge of changes to groundwater will help adaptation plans at the preserve and will prove useful in other Mediterranean-type coastal ecosystems.

Easterday and her team are focused on developing early warning systems for the region to help them understand how climate is changing and impacting species distributions. “It’s a place where we can develop some of the tools to be more proactive instead of reactive about climate pressures,” Easterday said.

Researchers from diverse disciplines are drawn to the preserve’s eight miles of wild coastline as well as its diverse habitats of chaparral, grassland, oak woodlands, coastal scrub, dunes, and closed-cone pine forests.

So far, scientists have counted 200 species of wildlife and nearly 600 plant species at this special place. “Whenever researchers visit and do field work, we expand the species list,” Reynolds said.

The data gets added to GIS to provide the digital twin of the preserve. Researchers add to it, and the open nature of the digital twin allows them to plug in their own research and influence others, while everyone gets a greater understanding.

The institute has been collaborating with Indigenous communities to incorporate traditional land management practices where possible. Practices such as prescribed burning have proved effective for reducing fire intensity while enhancing the quality of the landscape to culturally important plant species.

To date, the inventories have largely been on land, but marine inventories are under way in order to create land-sea connectivity in the face of climate change. The structure of the marine protected area off the coast and the mix of cold water from the north with warm water from the Santa Barbara Channel, yield the most diverse surfperch community in California. Also, the Point Conception State Marine Reserve is a protected area of 22.52 square miles, where no living marine resources may be taken.

The preserve is focused on protection. There are access points nearby, including at the Jalama Beach County Park, but the preserve is largely off-limits to the general public. In the future, access will be managed through docent-led hiking tours and volunteer opportunities. That gives the wildlife free reign, and it enables scientists, land managers, and Indigenous partners to see the land as it has long been and witness how a native coastal ecosystem really works.

Elsewhere along the California coast, there are efforts to restore connectivity for wildlife. But in this place, we can all see and understand what natural connectivity means, because the flow of species is unfettered across diverse habitat types.

Many discoveries have been made in the few years this wild property has been available for science, and more are certain to come.

“This landscape has a really powerful narrative to tell us in this moment in human history, and we’re excited to tell these stories,” Reynolds said.

Learn more in this story by The Nature Conservancy about the Dangermond Preserve. Read the Vision for a Wild Coast to learn more about the strategic plan for the Dangermond Preserve.

July 12, 2022 | Multiple Authors |

August 4, 2021 |

August 31, 2021 |