December 16, 2025

When Dutch explorers arrived on Easter Island more than 300 years ago, the legendary giant statues known as moai filled them with wonder. Looking around, they saw no trees, no signs of cordage, and a relatively small population. They couldn’t explain how the people of this remote Polynesian island, more than 2,000 miles from Chile, erected hundreds of these figures that stood three stories high along the coastline.

The narrative they constructed about Easter Island—known as Rapa Nui to locals—was one of ecological and societal collapse that would endure for generations. The explorers assumed the locals had cut down all the trees as part of the process for moving the statues. They also believed there must have been more people to move the monuments, but that a serious population decline had occurred. They speculated that overpopulation and depletion of resources led to war and cannibalism, culminating in a devastated island.

This cautionary tale of Rapa Nui is now being challenged by archaeologists Carl Lipo, professor at Binghamton University, and Terry Hunt, professor at the University of Arizona. They’re using remote sensing techniques and geographic information system (GIS) technology to uncover new evidence about the island’s history.

“As an island without trees,” Lipo says, “it’s pretty well suited for remote sensing.” When he and Hunt began their research in 2001, they had expected to add evidence to the collapse theory. But they found no signs of warfare—no weapons, fortifications, or traumatized skeletons.

To learn what really happened there, they began studying the island’s historical settlements, available resources, and agricultural practices.

The initial remote sensing methods Lipo and Hunt employed were born from masterful creativity. In 2001, satellite imagery didn’t deliver the level of detail available today, and drones weren’t yet widely accessible. Lipo said, “We started flying kites with digital cameras that had mechanical shutters, using little triggers to press the buttons with radio controls. We’d take photos of wherever the wind would take the kites, and then we’d stitch the photos together as best we could.” It would take months to document a site, and more time to process the imagery.

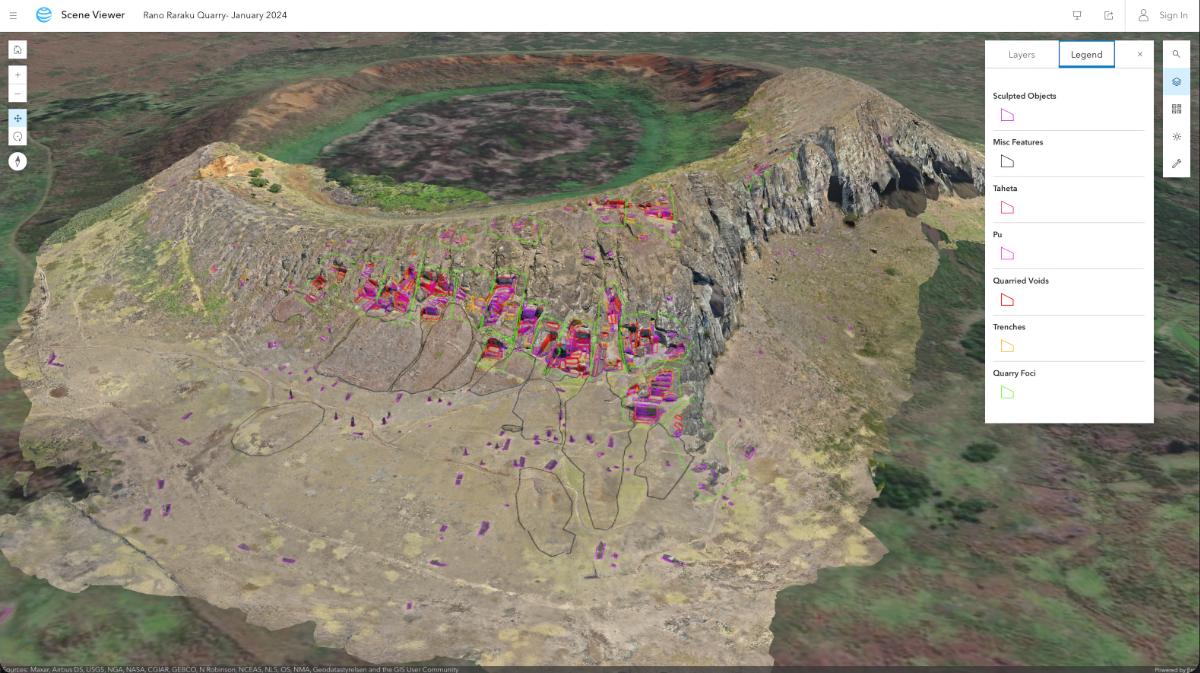

Advancements in remote sensing and GIS technologies, along with the democratization of drones, have created new opportunities for the researchers. They can now fly drones over Rapa Nui and capture high-resolution images of the entire island in just a few days. Using GIS, they can process the drone footage within hours and quickly layer on satellite images that provide robust detail, useful for quantifying change even at the ground level.

GIS mapping and analytics software has also been crucial for turning the research into something shareable. “We took 20,000 photos and were like, ‘Now what?’” Lipo said. “It was a challenge not only to figure out how we’d process the data, but how we could turn it into a product and share it in a way that was meaningful.”

There are many ways archaeologists can generate data, but it often ends up in a hard disk or in a file format that few people can use. GIS is helping turn the Rapa Nui data into a visual story anyone can understand.

The researchers went further still, using GIS technology to create a digital twin, or 3D replica, of the island. This means they can study Rapa Nui digitally, without damaging sites through excavations. They can also use it to share their data and models with locals, collaborate with other experts, and monitor changes to the landscape over time. The digital twin is proving to be an essential tool in efforts to engage the Rapa Nui community and uncover the truth about their past.

Studying images of Rapa Nui, Lipo and Hunt found that early inhabitants—in stark contrast to common theories—were living well within the means of their limited resources. In fact, they established sophisticated agricultural practices in a place that was not ideal for growing crops. The island’s soil was weathered and depleted of nutrients needed for plant growth. Yet, they were able to increase plant productivity by covering the soil with pulverized rock. This custom, known as rock mulch gardening, helped produce nearly half the food they ate, which included sweet potatoes, taro, yams, and bananas.

Further analyzing the island’s rock mulch gardens, the researchers calculated that previous claims regarding the amount of food they produced were over-estimated. This finding has helped verify that Rapa Nui’s population was never more than a few thousand people at any given time.

Equally sophisticated among early Rapa Nui people were their water management practices. Lipo and Hunt use thermal imaging drones to study water features around the island. There are no permanent surface freshwater sources, leaving many scholars to believe forest loss was to blame. However, imagery analysis with GIS has helped reveal other water sources that sustained the islanders. Along the coastline are locations where groundwater emerges at the tide line, known as submarine groundwater discharge. These springs would have been resilient to droughts. And though the sea water in these locations is brackish, the people of Rapa Nui built well-like traps to capture groundwater before it mixed with saltwater.

While there is no question the island experienced deforestation, the research Lipo and Hunt have collected demonstrates that trees were not critical to the community’s survival. Furthermore, the trees weren’t used to move the famous moai. “Palm wood isn’t very strong,” says Lipo, “so the trees could not have supported the weight of the statues.”

Locals have long claimed the moai “walked out” into the landscape. In a 2012 National Geographic feature, Lipo and Hunt suggested a new theory that, in a way, speaks to this account. They proposed that the Rapa Nui people engineered the statues to move in a rocking motion, and that it only took a little physical effort and some rope to transport them into place. A video to support this theory shows a team organized by the researchers demonstrating how it could have worked.

Lipo and Hunt have surfaced a story of ingenuity, countering those of catastrophe. Based on imagery analysis and archaeological data, it’s evident that the islanders found inventive ways to live sustainably—and did so until contact with Europeans in 1722.

Outsiders brought disease, violence, and slave raids. But up until that point, the evidence shows impressive adaptability. It shows that this was a collaborative community. It shows that rather than being responsible for their own downfall, the people made the most of what was available to them. “They had no choice but to figure it out,” Lipo said.

In this way, Rapa Nui research offers modern-day societies hope for how we can adapt to overcome our own challenges. And the digital twin of the island connects the local community to prove their history is one to be proud of.

The latest Rapa Nui research from Lipo and Hunt is available on PLOS One. Learn more about how drone mapping software creates detailed 3D visualizations that archaeologists can use to query the past.