You need the cyber intelligence expert working in close cooperation with the geoexpert to find the best solution and visualization.

When Russia annexed the Crimea region of Ukraine in February and March 2014, it shocked the world and was a surprise even to many experienced analysts and organizations monitoring Russian activity. But a few experts saw indications and telltale signs beforehand.

Volker Kozok, a lieutenant colonel and cybersecurity expert in Germany’s armed forces, was one of those few. He tracks digital security threats and devises countermeasures. The job gives Kozok a front-row view into the current age of hybrid warfare.

Today’s military conflicts rarely play out only on physical battlefields. They are just as likely to include cyber attacks; assaults on critical infrastructure; and various forms of weaponized information, intended to sow seeds of confusion and insecurity in a population.

In the case of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, what Kozok and his colleagues noticed in January 2014 was a clandestine opening salvo from Russia. They observed that Russia was installing what looked like an undersea cable across the Strait of Kerch, a narrow waterway between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. As they monitored progress on the 46-kilometer cable, it became apparent that its end point was the peninsula of Crimea.

The cable’s existence strongly suggested Russia was making a move to connect Ukraine’s critical infrastructure with Russia’s. In particular, it looked like Russia’s cable would carry high-speed internet communications that could bypass Ukrainian service providers.

Kozok’s team members bolstered that inference through the sophisticated use of geographic information system (GIS) technology. They could examine the cable’s construction in the context of location on a map that showed the world’s undersea cables and the nodes that connect the internet. From this, the team could deduce that Russia was aiming to control online communications. In the annals of warfare, it was a defining moment.

“It was the first time a country had organized a military attack while also being very smart about planning for connectivity using a sea cable,” Kozok explained. “Someone had to drive to Crimea as a tourist [before the invasion] and figure out the cable’s entry point. They had to make those plans without actually controlling the country.”

Russia continued to employ hybrid war techniques in Ukraine. Russian hackers launched a cyber attack against Ukraine’s power grid in 2015, cutting off electricity to 250,000 people. Almost exactly a year later, hackers caused another blackout.

It is now abundantly clear that cyber attacks present a danger to more than computer systems. Cybersecurity must now include the critical infrastructure—including utilities—that undergirds communities.

“The cyber warfare in Russia and Ukraine is one of the main interests in Germany, because we saw a lot of similar hacking,” Kozok said. “We see hacks against NATO and against German governmental and commercial systems. Our intelligence community has developed a wide-ranging response to this undeclared cyber war.”

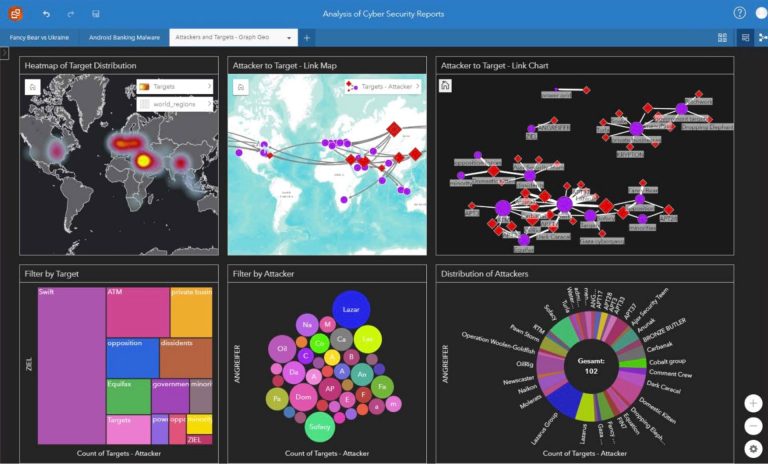

As hybrid warfare has evolved, experts like Kozok have developed a “hybrid intelligence” approach. In the past two years, Germany’s armed forces refined its capabilities by using GIS to organize large amounts of intelligence data in the context of location.

“First, you have to bring together the raw data you have in different IT forms,” Kozok said. “Then you have to combine it with the information from other sources. You need the cyber intelligence expert working in close cooperation with the geoexpert to find the best solution and visualization.”

You need the cyber intelligence expert working in close cooperation with the geoexpert to find the best solution and visualization.

Data analysis takes many forms. It can be as basic as visualizing a terrorist attack against the backdrop of a city’s underground infrastructure, or as complex as plotting the spread of propaganda by using artificial intelligence to sift through social media feeds.

The hybrid approach has proved especially useful in handling a barrage of cyber attacks against German interests in recent years. Many attacks appear to originate from Winnti, a group of hackers headquartered in China. By adding a location component to related data, officials can more easily assess the problem and take action.

“If I show a general some source code, he won’t understand what I’m doing,” Kozok said. “But if I can show him on a map that a Winnti tool has been attacking certain parts of Europe, he might see that it’s mostly in the European Union, or perhaps it’s an attack on NATO, which means the military is probably involved. With another map layer, I can show him how many of the attacks are against chemical companies.”

Kozok has found that location intelligence provides a common parlance to understand cyber intelligence. “The generals understand that the world belongs on maps,” he said. “It’s how we show them the connections linking every analysis we have.”

Learn more about how national and corporate security experts use GIS to manage cybersecurity activity.