March 2, 2022 |

April 27, 2023

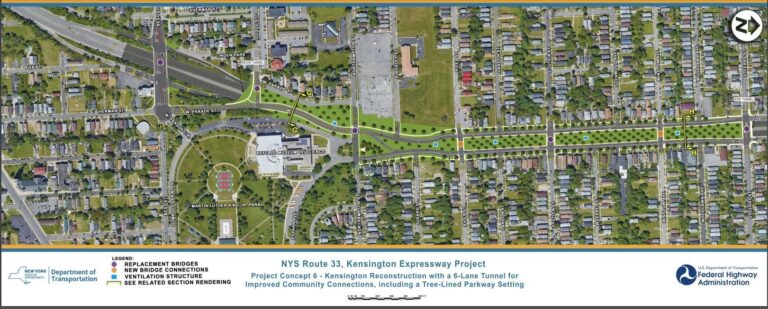

Residents of Buffalo, New York, are celebrating plans for a much-needed upgrade to the six-lane, sunken Kensington Expressway, funded by a $55 million federal grant. The work will reconnect and revitalize predominantly Black neighborhoods divided by highway construction in the 1960s. Now, the community is using maps to remember and teach others the reasons that the project is so vital.

Before the highway came, this place was special. Those who stayed, as decades of traffic noise and pollution choked their quality of life, hope the new five-block tree-lined cover for the highway will help revive their neighborhood. The US Department of Transportation (USDOT) Reconnecting Communities Pilot (RCP) Program grant will add trees and green space and extend the city’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Park.

In Buffalo, Humboldt Parkway’s 86-foot-wide median and mature elm trees created a “ribbon of green that wove its way through the city, connecting its parks and neighborhoods.” The Humboldt helped Buffalo earn distinction as the best-planned city in the US before crews took out a section and razed more than 600 properties to make way for the 1.25-mile Kensington Expressway project. The expressway severed streets and blocked connections from either side. Instead of green spaces, concrete retaining walls that climb to 27 feet in some areas are now the most visible scenery.

“We would take a walk through Martin Luther King Park and play,” recalls Edna Gayles Kay, a teacher who lived in the Hamlin Park area as a child. “It was a beautiful area. I loved being a part of Humboldt. I think we’re going to be blessed with this [reconnecting] project.”

Buffalo’s story is hardly unique.

Maps and location data provide a powerful record of how highway construction dismantled hundreds of racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods across the country beginning in the 1950s. Now, digital maps and dynamic 3D models capture visions for renewal among Blacks, Latinos, Asians, and other groups. USDOT approved 45 Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program grants in 2023, including capping the Kensington Expressway.

Federal highway policy of the mid-20th century allowed for, and often promoted, the construction of highways that severed cities and towns across the nation. According to USDOT’s Beyond Traffic 2045 Report, routes were chosen where land costs were the lowest or where political resistance was weakest, cutting through non-white communities more often than not. This left a legacy of disenfranchisement and underinvestment that new programs such as RCP will begin to address.

Interactive maps and 3D models created with geographic information system (GIS) technology show how the construction of highways changed the national landscape. Today, communities exist behind walls of concrete or straddle deep trenches that restrict mobility as in Buffalo. The isolation contributes to higher-than-average unemployment in many neighborhoods. In other locations, residents are left with high air pollution and highways without safe crossings.

Projects approved for Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program grants convey that hope and vision through thoughtful and inventive designs.

The City of San Jose, California, received $2 million for a $2.5 million study and conceptual design for improving Monterey Road. Area residents want to see the 100-foot-wide, six-lane highway become a welcoming, walkable boulevard. It is hardly that today. Between 2019 and 2022, there were 476 collisions here, including 42 fatal and severe wrecks and 357 injuries.

This location has a rich history. In the 1700s, Monterey Road was part of “El Camino Real” or the royal road, described as California’s first highway. It connected 21 Franciscan missions over 600 miles.

Later, Monterey Road became part of a multistate stagecoach route. Horses powered this early form of public transportation. Today, the thoroughfare has speed limits of up to 50 mph and few crossings. These conditions limit travel in all directions for the 84,000 people who live nearby. Neighboring Union Pacific Railroad freight and passenger trains make the area more isolated and inhospitable.

North Peoria Church of Christ in Tulsa, Oklahoma, received $1.6 million for a $2 million study for removing part of Interstate 244 where it bisects the historic Greenwood neighborhood. This is the same community where a mob destroyed the area known to many as Black Wall Street in 1921 and left hundreds of people dead. Decades later, Greenwood “suffered the punishing effects of urban renewal,” according to the church’s application. The congregation also wants to establish a community land trust that benefits Greenwood and North Tulsa residents, especially those who saw their homes taken unjustly and below market value through eminent domain.

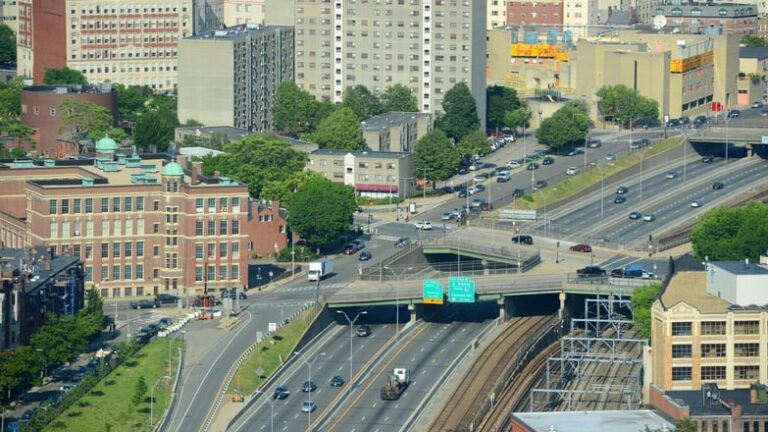

The City of Boston, Massachusetts, received $1.8 million toward a $2.4 million study to address physical divisions in Chinatown. The city wants to build an open space over Interstate 90 and link the surrounding streets, including areas between Shawmut Avenue and Washington Street.

America’s Chinatowns—once lively cultural designations in major cities—are disappearing as new construction arrives. Boston’s historic Chinatown once ranked as the third-largest ethnic neighborhood of its kind in the US. Chinese American families owned homes, as well as thriving shops, restaurants, and other businesses. Today, old and new maps and location data tell a dramatically different story. Twenty percent of the homes are gone, along with 12 percent of the businesses and 10 percent of the land itself. Chinatown now ranks as Boston’s most polluted neighborhood. There is little open green space or affordable housing. Highway construction in the 1960s led to land seizure and demolitions, including the removal of the thriving Hudson Street neighborhood.

Highways displaced at least one million people and businesses, according to a USDOT report. In many instances, authorities leveled entire vibrant, affordable, and accessible neighborhoods. Those who stayed were split up socially, economically, and by physical barriers.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) made possible the first-ever federal Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program. The RCP grants are designed to fund community-led programs to right past wrongs. Neighborhoods that were “cut off from opportunity and burdened by past transportation infrastructure decisions” can apply for grants.

The Buffalo project is shovel-ready with environmental assessments underway. With additional funding from the state of New York, the project is expected to break ground in early 2024.

Most of the RCP grants go toward planning. Among the projects approved, 12 fund planning to cover or make a bridge over a part of a highway. Doing so would open up space for parks and housing and add crossings for pedestrians and bicycles. Some projects aim to reduce pollution. Eleven grants focus on removing physical barriers, such as sunken highways and highway ramps.

Maps Document the Dark Truth of US Highways

On the website Segregation by Design, New York architect Adam Paul Susaneck says about 180 municipalities received federal funding for highways. Susaneck asserts that past damage to communities that were home to people of color was intentional and systematic. On a 1955 map of Rochester, New York, the term “slum clearance” labeled city blocks shaded in blue, identifying homes and businesses to be removed.

Thanks to the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, areas fragmented by highways finally have a chance to imagine a better future. Sketching their visions through maps and renderings is where the work starts. In the process, the long-separated neighbors are finding an unexpected opportunity to strengthen old bonds.

Learn how GIS helps create and sustain equitable communities and design and build more equitable transportation systems.

March 2, 2022 |

November 9, 2021 |

October 13, 2020 | Multiple Authors |