From May to October, when wildfire season peaks in the Northern Hemisphere, there’s not much downtime for the 60 National Guard intelligence specialists who make up America’s FireGuard program.

“We’re pretty much full on,” said Air Force Captain Gregory Wagner, with the Colorado FireGuard team, citing the team’s 12-hour shifts and no days off. “These guys grind and produce information products.”

It’s demanding work with considerable consequences. The FireGuard program’s military analysts apply their intelligence skills—typically used for overseas operations—to a civilian mission that’s saving lives and property. Operating from just two locations, in California and Colorado, they provide continuous wildfire monitoring for the entire United States and Canada, detecting fires when no one else is watching.

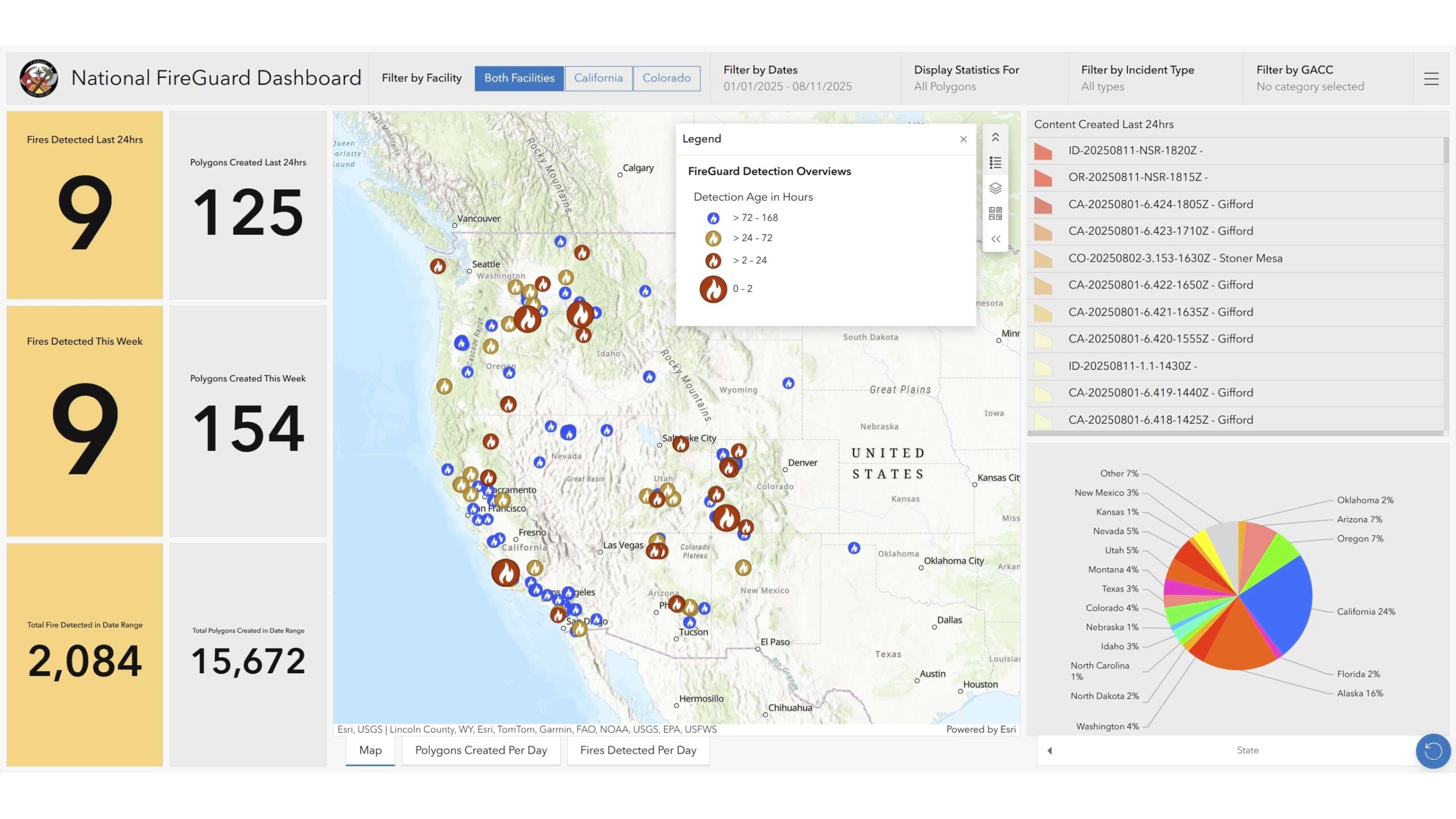

“We excel at initial detections in remote locations and at odd hours,” said Major Ron Strahan, commander of the California National Guard’s FireGuard team. The results speak for themselves: since 2019, FireGuard has generated more than 127,000 maps and location analyses covering over 8,872 fires across the United States. In addition, both California and Colorado teams generated over 44,000 geospatial products covering over 2,600 fires across Canada during the 2023, 2024, and ongoing 2025 fire season.

The teams work with sophisticated geographic information system (GIS) technology, mapping near real-time satellite and sensor data to relay crucial information for firefighters on the ground.

This constant vigilance fills a critical gap in wildfire response. Traditional fire detection often relies on someone spotting smoke or flames and calling 911. By then, precious time has been lost. In remote areas, a fire could burn undetected for hours or even days.

“We’re over some incidents where aircraft just can’t get up and fly because of crosswinds,” Strahan said. “Sometimes if there are multiple incidents going on, there’s only so many aircraft to go out and look at them, so that’s the real gap we fill with our 24/7/365 monitoring.”

FireGuard analysts have been the first to detect fires that have threatened thousands of lives and homes. Their rapid detection and mapping capabilities have proven invaluable for evacuation planning and resource deployment.

During the 2021 Marshall Fire in Boulder County, Colorado, high winds prevented any aircraft from flying during the first eight hours. FireGuard analysts provided the only intelligence products available to firefighters and emergency managers, facilitating the evacuation of about 35,000 people as the fire consumed more than 6,000 acres.

“One of the most critical components in saving lives and property during rapidly escalating fires is being able to make decisions based upon accurate and reliable situational awareness,” said Mike Morgan, director of the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control, in a news report about the Marshall Fire. “Without the information provided by FireGuard, situational awareness at all levels would have been significantly degraded.”

California had a similar need for situational awareness in 2020 when the Creek Fire trapped residents near the Mammoth Pool Reservoir. Information from FireGuard supported the California National Guard in helicopter rescues of 396 people and 27 animals.

FireGuard reports integrate with the National Interagency Fire Center’s open data site, built with the cloud-based ArcGIS Online platform. Data, maps, and analysis tools move seamlessly across agencies—reaching more than 33,000 firefighters and emergency managers. Available analytics include fire risk levels, such as closeness to infrastructure and homes. FireGuard’s intelligence reaches firefighters on the front lines, and up to 92 percent of firefighters can now access the data via mobile devices.

FireGuard started as a California pilot program in 2019, through a strong interagency partnership among the US Department of Defense, the military, several federal civil agencies, and the Civil Applications Committee led by the US Geological Survey which provides the required legal oversight.

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, wildfire management faced unprecedented challenges. Fire crews typically travel thousands of miles during fire season, but the pandemic created new concerns about virus transmission. There were also unknowns related to how wildfire smoke might affect those who had contracted COVID-19. In response, the FireGuard program received $5 million in funding to expand its remote detection work nationwide.

When smoke from the 2023 Canadian wildfires blanketed New York City and Washington, DC in an apocalyptic orange haze, it triggered a call from the National Security Council at the White House to add support for Canada.

The expansion of FireGuard revealed just how critical the technology had become. During the 2024 Jasper Fire that devastated half the town of Jasper in Banff National Park, FireGuard analysts were the only source of available intelligence. The maps and analysis guided evacuations and helped firefighters build strategic defenses as the fire advanced.

“Because of the vastness of Canada’s forested landscape, they don’t have aerial assets or any other intelligence platform to give them indications of where this fire is at, where it’s going, how big it’s getting,” Wagner said.

FireGuard integrates satellite data with human expertise. It uses Department of Defense sensors and civilian weather satellites, running the data through algorithms that merge multiple sources. Human analysts then review the results to separate actual fires from false positives, like hot rocks or industrial heat sources.

The human element remains essential. “Our biggest asset is our analysts who do the work because they’re looking at all of our data sources and correlating that to draw that operational picture to feed to the firefighters on the ground,” Strahan said.

These aren’t just desk-bound analysts. Some FireGuard crew members split their time between interpreting satellite data and cutting fire lines with hand crews on active wildfires. In California, several analysts work six months with FireGuard, then spend six months on the ground—gaining direct experience with the fires they monitor.

This dual role requires serious physical conditioning. To earn their coveted “red card” firefighter certification, analysts must pass the demanding pack test—carrying 45 pounds for three miles in 45 minutes. The test qualifies them for arduous duty firefighting, the same standard required of frontline wildland firefighters.

“We have a very robust training program,” Wagner said. Coursework covers basic firefighting skills, suppression equipment, safety protocols, and fireline construction. A course on wildland fire behavior teaches analysts to identify how fuels, weather, and topography create dangerous fire conditions—critical knowledge for interpreting satellite data.

The rigorous program creates analysts who can not only interpret thermal signatures from imagery data—they can understand how fires behave on the ground because they’ve studied them. They can also more adeptly communicate critical information to firefighters.

Sean Triplett, who until recently served as team lead for tools and technology for Fire and Aviation Management with the US Forest Service, helped develop the FireGuard capability and is now working on the next revolution in wildfire detection and response with a dedicated satellite program led by the nonprofit Earth Fire Alliance (EFA).

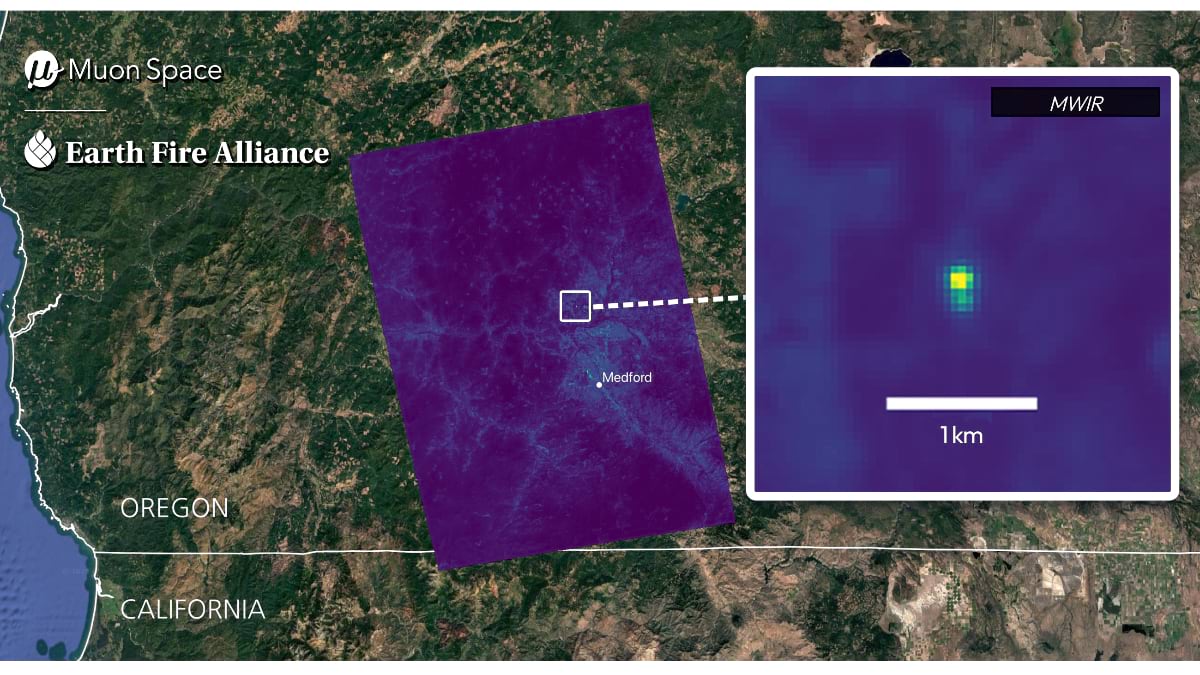

The FireSat constellation, the first satellites specifically designed for the global wildfire challenge, will focus on detecting fires when they are small and monitoring their movement across the landscape, providing unprecedented spatial resolution and revisit rates. The prototype satellite launched in March 2025, with the first three operational satellites slated to launch in mid-2026.

“EFA and our partner Muon Space intentionally planned the first FireSat as a one-year prototype flight,” said Triplett, who leads Data Integration & Operations at EFA. “Because this is brand-new, advanced infrared technology purpose-built for wildfire, we wanted time to validate the system performance, and sample data and data delivery infrastructure with our early adopter fire agencies.”

FireSat’s revolutionary design includes dual mid-wave infrared channels that can detect both the intense heat of active fire fronts and the cooler residual heat from burn scars left by dissipating or prior fires. The satellite’s sensitivity also enables it to detect fires by orders of magnitude smaller than those visible to existing systems, e.g., the size of a one-car garage vs. two football fields. These capabilities address fundamental limitations of current satellites, which were designed for general Earth observation rather than fire-specific detection and monitoring.

“The first data from the FireSat protoflight confirm the system is performing as expected—detecting small fires unseen by existing space-based systems, capturing multiple fire fronts simultaneously, and distinguishing intense fire fronts from burn scars to reveal available ‘fuel’ and potential progression patterns,” Triplett said.

When fully deployed by 2030, the FireSat constellation will provide global coverage every 20 minutes—a dramatic improvement over current systems that may take hours or days between observations.

EFA aims to facilitate access to critical wildfire intelligence by integrating high-fidelity data from FireSat with other systems like FireGuard to build a more complete common operating picture. Integration of FireGuard and FireSat data would represent more than just technological advancement—it would create a comprehensive wildfire data network.

The Alliance’s approach to a layered sensor network has the potential to provide a three-dimensional look at fires, combining horizontal views from ground-based cameras with vertical satellite perspectives. It could also enable a concept the military calls “tipping and cueing,” where one system can alert another to investigate further. While well-funded states like California and Colorado have robust fire programs, many other states and fire-prone areas lack similar resources.

“I live in Idaho where we have a very small fire program,” Triplett said. “The state has just a couple of GIS people, but fire is a big player on our landscape.”

This disparity extends globally. While attending recent international conferences, Triplett witnessed the stark differences among fire management capabilities worldwide.

“There were more than 50 countries at a recent event hosted by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome, and it was motivating to learn about the diverse capacities and how certain countries are starved for resources in terms of detecting and monitoring fires.”

EFA’s nonprofit structure aims for accessible data distribution, with the intent to provide the same high-quality wildfire intelligence from remote, under-resourced areas to well-populated, wealthy regions. Achieving this could transform global fire awareness, particularly in developing countries where fires often burn undetected and unmanaged.

FireGuard’s mission comes down to a simple principle: awareness saves lives. In an era when wildfires are becoming more frequent, more intense, and more destructive, having eyes in the sky watching 24/7 provides the early warning needed to make a difference to both people and property.

As extreme heat and drought fuel more intense fires worldwide, programs like FireGuard represent humanity’s best hope for staying ahead of the flames. Through constant vigilance and cutting-edge technology, these digital guardians are helping ensure that no fire goes unnoticed, no threatened community goes unwarned, and no firefighter goes into battle without the best intelligence available.

Learn more about how GIS is applied to prepare, mitigate, suppress, and recover from wildland fire.