October 13, 2020 | Multiple Authors |

December 17, 2020

Over the past decade, leaders in King County, Washington, have emerged as innovative in the fight for equity and social justice (ESJ) in local government. They have found new ways to use data to shape more equitable policies and track progress over time. And an unassuming county department is leading the charge—the King County GIS Center. This center’s small team, with leadership and support from Greg Babinski, uses geography to fuel progress.

In late 1960s Detroit, a young Babinski first learned about geography against a backdrop of social unrest and racial inequity. One of his teachers was William Bunge, a controversial figure who pioneered the use of applied geography for social justice.

Bunge co-led what he called geographic expeditions—not outward to far-flung reaches of the earth but inward to his own urban environments of Detroit and later Toronto. The goal was to understand people’s lived experiences and see how someone’s location contributed to their quality of life. He partnered with Gwendolyn Warren, a young Black woman who helped surface and map racial inequities in Detroit.

At the time, Bunge’s approaches led to him being labeled a communist sympathizer, losing his job, and living in exile in Canada. But Babinski never forgot what he learned from Bunge, taking many ideas with him as he navigated a career that eventually led him to King County in Washington state.

Babinski began working at the King County GIS Center in 1998. Since then, he’s witnessed a growing realization of the need to focus on equity and social justice, as well as the power of geography as one of the best tools available to do that work. GIS, or a geographic information system, is spatial analytics technology that layers location data with other kinds of information to produce maps and other visualizations for new insights.

Babinski recalls an early project where the county planned to purchase an abandoned rail line and convert it into a recreational trail for community use. The project came with a hefty price tag—$100 million. County executive Ron Sims came to the GIS team and asked for a geographical analysis of the project. Who would it impact, and how many recreational trails and parks were already in the area? They did the analysis and made a crucial discovery—the area was affluent and already had the highest concentration of trails and parks around. With that awareness, the county decided not to spend the money, shifting its focus and budget to other projects where people would benefit more.

Later, Sims asked county demographer Chandler Felt to research how the demographics of residents affected their success in life. The disturbing results showed that King County residents experienced a 10-year gap in life expectancy, as well as lower health and income, depending on where they lived. The areas with the lowest life expectancy were also the areas with the most people of color. This was a shocking discovery for Babinski, one that helped forge his drive to improve equity.

“Race and the place that you’re born or where you live shouldn’t be a predictor of your ability to thrive and succeed in life,” Babinski said. “Right now, they are.”

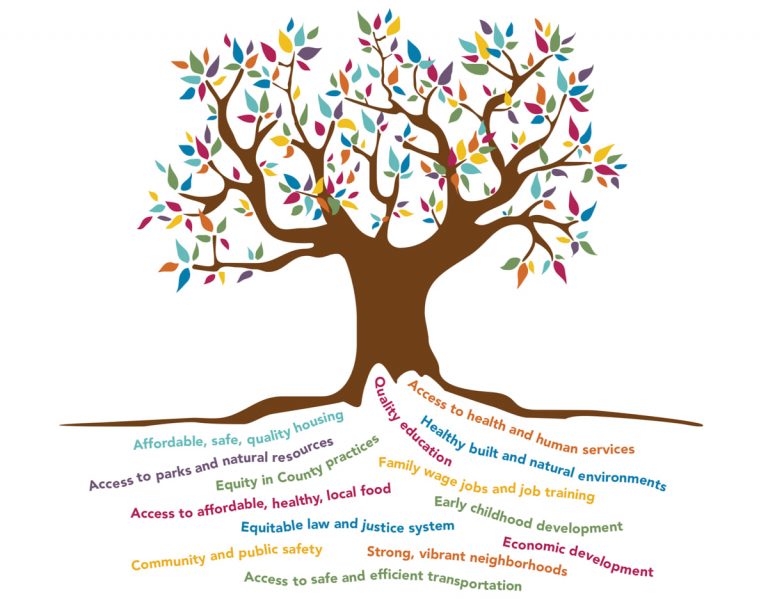

These experiences and analyses evolved into the practice of applying an equity lens to every potential project and policy in King County, with the aid of spatial analysis. The work also helped solidify a key concept for Babinski: geography can help government leaders answer one of the most important questions to improve quality of life for residents—Where is the need greatest?

What other questions can geography help leaders answer? How else can GIS be used to promote equity? Babinski, the King County GIS Center team, and other King County leaders began working to expand a framework that others could learn from and use.

In 2018, the King County group including Babinski, then chief equity officer Nicole Franklin, and others helped host an equity and social justice track at the annual conference for the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA). The session was standing room only, and the buzz was long lasting, with passionate professionals deciding to form a workgroup to further the cause.

In 2019, Babinski was awarded an EthicalGeo Fellowship through the American Geographical Society to develop a fleshed-out set of GIS for ESJ best practices. Alongside a core team, he began the work of creating a formal document, not with the goal of setting anything in stone but with the hope that it would spark conversations, influence critical thinking, and be improved over time. The following are among the guiding principles:

Franklin and Babinski evolved the best practices into a half-day Intro to GIS for ESJ workshop the King County GIS Center staff teaches to other city leaders. At first, they offered a half-day afternoon course, presenting to leaders from cities such as San Jose and Seattle. As interest soared, they soon had to add a morning time slot for people on the east coast. The course is now certified by URISA.

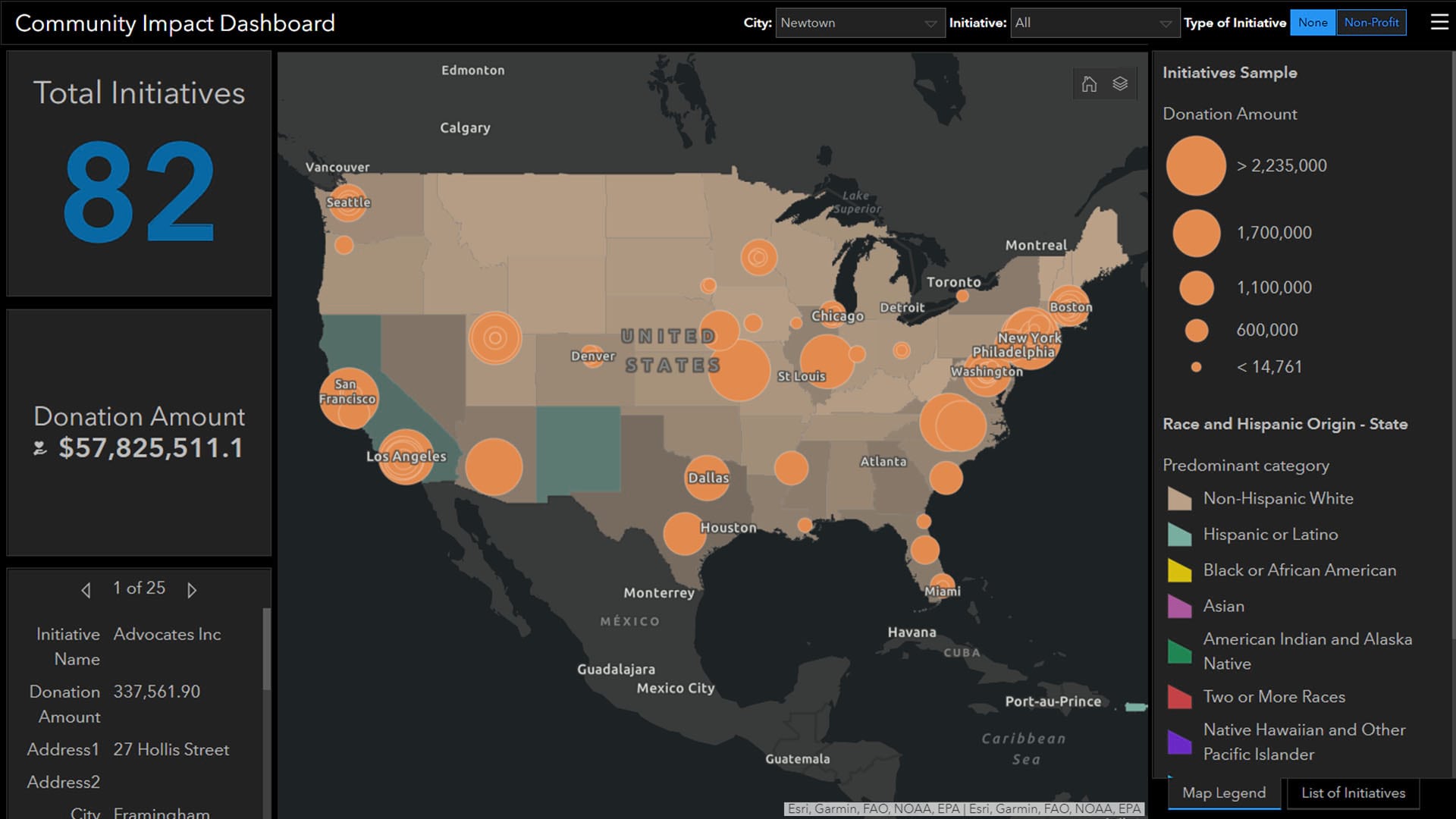

While King County’s impact on equity issues is evident in its thought leadership and knowledge sharing, it has also been doing hard work within its own community.

One salient equity issue the county is tackling is the digital divide—not all community members have equal resources such as computers and Wi-Fi. With COVID-19 further disconnecting people, county and school board representatives say it’s more important than ever for families to have access to the internet. For many children, it’s the only way to access their education. The King County GIS team used geographic analysis to pinpoint areas lacking coverage, sharing that information with service providers looking to expand.

In parallel with King County’s work, the City of Tacoma’s senior policy analyst Alison Beason used GIS to create an equity index of the city’s population, measuring digital equity and other characteristics such as livability and health. The team also contributed analysis to help city leaders decide where to allocate funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act—again by identifying areas with greatest need.

Babinski points out that equity and social justice are long-term issues—they have persisted for decades, and improvement can only be measured over long time periods. Because of that timeline, spatial analysis must be executed consistently. He says the work must be done with a high degree of precision, so it stands the tests of time.

“GIS for ESJ is not a one-year project,” he said. “It’s not a five-year effort. It’s really generational, because if we want to break this cycle, so that race and place don’t correlate with thriving throughout the course of your life, we’ve got to look at this over a generation or generations.”

Beyond longevity, Babinski shares that ESJ work must stand up to critics and naysayers. He feels GIS is well positioned to assist in that goal—showing real numbers in a visual format (often on a map) that communicates viscerally with stakeholders and community members.

Babinski also seeks to inspire the next generation of geographers to take up the mantle of using GIS for equity. URISA is similarly focused on engaging young, up-and-coming geographers to do this work, through its Vanguard Cabinet of Young GIS Professionals and training opportunities such as the URISA GIS Leadership Academy.

While teaching a PhD-level GIS for Public Policy class at the University of Washington, Babinski noticed that many of his students’ projects had a bent toward social justice issues. He shared the lesson he was taught in 1960s Detroit—that sharing the lived experience of the people in the community can spark change.

“Community input is not just nice to have, it’s really critical to truly understand how members of the community perceive their own geography and how they perceive the things that the government is doing to it,” he said.

After the death of George Floyd, many local governments have put more focus on social inequities, and others are duplicating what King County is doing. Multiple projects are under way, such as equitable housing in Houston, addressing inequality in Oakland, and examining driver’s license suspensions in New York.

Babinski is one of many geographers and GIS professionals to adhere to a code of ethics, believing they have a duty to use technology (GIS in particular) for the benefit of all society. He has his own description of GIS, tying it fundamentally to the work of equity and social justice. In his words, “The GIS profession uses geographic theory, spatial analysis, and geospatial technology to help society manage Earth’s finite space, with its natural resources and communities, on a just and sustainable basis for the benefit of humanity.”

Learn more about how GIS helps people examine racial inequities.

October 13, 2020 | Multiple Authors |

September 1, 2020 | Multiple Authors |

August 11, 2020 |