August 4, 2021 |

January 25, 2022

Unlike Nevada’s lawmakers who temporarily descend on Carson City each legislative session before leaving again, a group of mule deer has taken root. It’s an increasingly rare sight to see a herd of this size anywhere else in the state and across the western US, and striking that they have chosen the state capital where they may be hoping to have an influence.

A particularly harsh winter nearly two decades ago “reset the whole bar” for mule deer in the state and is still being felt today after 30 percent of the population didn’t make it, said Cody Schroeder, a big game biologist and mule deer specialist at the Nevada Department of Wildlife.

Ongoing drought conditions in already arid Nevada haven’t helped, drying out some of the high-quality vegetation that mule deer need. Then there are other obstacles: grazing competition, invasive species, urban encroachment, changing climate, and healthier predators.

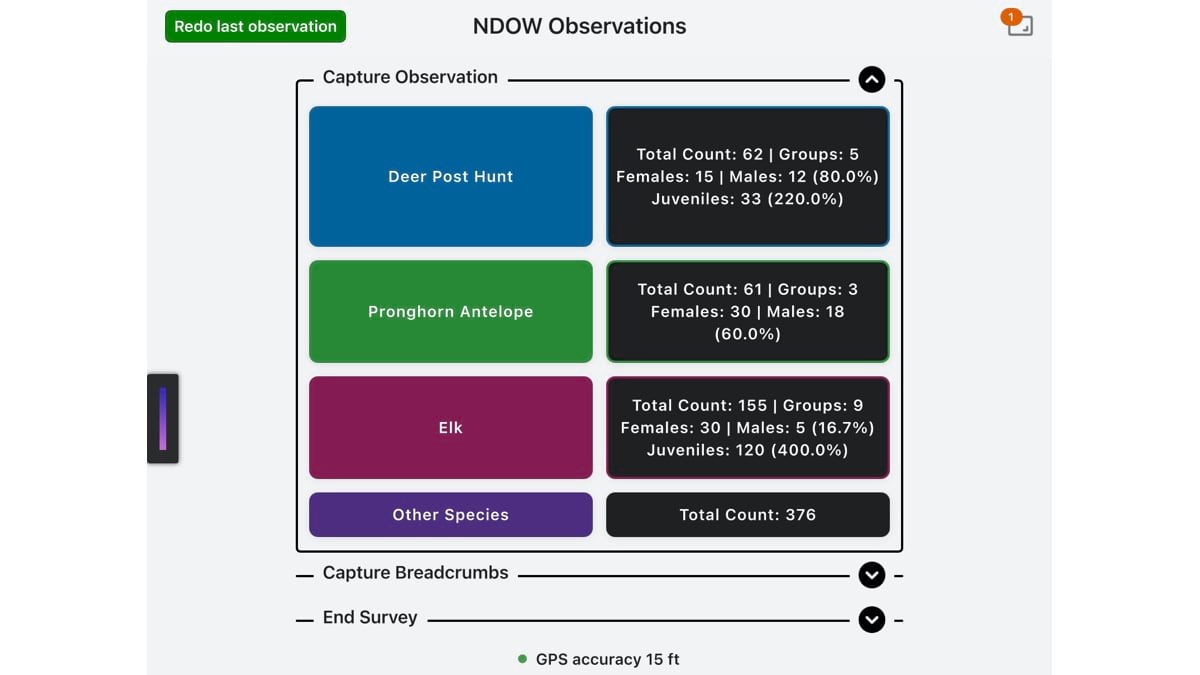

To get a handle on the status of the species, and to allocate the right number of hunting tags to manage herd sizes, the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW) takes to the sky in helicopters to tally numbers, gender, age, and health of the mule deer below. Until recently, that involved logging data on paper while in the air and often not being able to analyze or visualize the data until much later.

“Now, we can see right away where deer are concentrated and where we have conflict areas,” Schroeder said

NDOW gathers population details and conducts analysis using geographic information system (GIS) technology that allows the agency’s biologists to piece together a landscape-level understanding of wildlife and ecosystem health. The data feeds decisions to address the ongoing mule deer decline.

With recent advancements in how NDOW conducts aerial surveys, decisions to balance the mule deer’s precarious position are informed by a real-time understanding of populations and conditions.

Cody McKee, a biometrician and elk and moose specialist at NDOW, has been working on streamlining data collection, management, and analysis for several years. He was tasked with gathering historical aerial survey data from spreadsheets and filing cabinets and realized that NDOW needed to modernize its workflow to make a leap forward in efficiency.

“Helicopters are an important part of what we do, for that bird’s eye view of the landscape that gives our biologists a holistic perspective,” he said. “It’s also a dangerous part of our job, and at least for me, the question ‘Is this the last time I get into this ship?’ is always in the back of my mind. We need to be sure that we are making the most of our time in the air.”

McKee reached out to Esri to fit capabilities of ArcGIS Survey123 and ArcGIS QuickCapture to create one app on one device for the aerial surveying task, and reduce the time spent looking down instead of forward, where hazards lie. The group worked through iterations to greatly improve what had been a paper-based process, using buttons rather than entry fields to standardize observations.

Previously, biologists would take notes and jot GPS points while in the helicopter, and then back in the office they would spend a lot of time typing data into spreadsheets and then merging data and fixing transcriptions errors. NDOW estimates that biologists were spending half the time they spent in flights to get the data usable, so if they spent 1,500 hours flying, it would take an added 750 hours before the data could be analyzed.

Now, notes and photos are tagged with position and data goes right to a shared database. The time saved on data wrangling gives biologists a chance to reflect. And they can study the data to see trends.

For mule deer, and other species, the data supports queries about the cause of decline.

“We used GIS to map the overlap between where mule deer and feral horses are and their preferred habitat,” Schroeder said. “We’re also looking at other things that are impacting them, such as invasive grass, the drought, and where mountain lions cluster and have kills.”

One of the most vexing problems that Nevada land managers face is the growing impact of “cheatgrass” – a type of grass that steals water from native vegetation – that’s sprouted in large areas where big fires have burned sagebrush habitat.

“Southern Oregon, southern Idaho, and Utah have had a big problem with cheatgrass, but Nevada has had a cheatgrass invasion,” Schroeder said.

In winter, mule deer rely on brush sticking up out of the snow. When cheatgrass is present, native shrubs aren’t, so deer have nothing to eat.

The grass flourishes in Nevada’s lower arid elevations, where it has altered whole ecosystems.

“We’ve documented how cheatgrass changes the natural fire frequencies from 100-to-300-year cycles down to 3-to-5-year cycles,” Schroeder said. “It used to be that fire in our ranges were rare, but now they burn over and over.”

More than 80 percent of the land in Nevada is public, and much of it is managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) which is responsible for herd management of burros and feral horses. BLM sets the Appropriate Management Level of herds and works to keep populations down, noting that an appropriate number in Nevada would be 12,811. However, it estimates there are 42,994 horses and 4,087 burros as of March 2021 in the state.

Schroeder teamed with David Stoner from Utah State University and other researchers on a paper about the impact of feral horses on other big-game species.

The research involved the spatial analysis of the range of different species such as mule deer, big horn sheep, elk, and pronghorn antelope overlapped with the range of feral horses. The paper noted that expanding populations of feral horses is a concern for all species.

Researchers are using GIS to drill into the impact feral horses are having on waterholes during the drought, on land with little to no vegetation, and what species are displaced and where.

“The research aims to determine how many horses is too many, and where exactly the conflicts arise around water and forage,” Schroeder said.

Aerial surveys are a key tool that biologists use to make all manner of wildlife management decisions, because of the perspective it gives them.

“Once you get up into a helicopter, you realize just how connected everything is,” McKee said. “While there are many miles separating mountain ranges, the animals we’re managing have the ability to cover those miles in a few hours if need be.”

With streamlined data collection, NDOW biologists have started to look at pressures spatially, and ask geographic questions from the survey data about population health versus range conditions.

“This is going to help us investigate things and focus our habitat restoration efforts where we can create the most connectivity for wildlife,” Schroeder said.

In the mid-1990s, the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies developed a Mule Deer Working Group that monitors the population across its full range, addresses disease concerns, and fosters best management practices.

NDOW biologists have shared their aerial survey approach with the working group and received great interest. Peers in all states have the same focus on ensuring longevity of species and making decisions that can sustain populations. With all the pressures mule deer and other species face, this group wants forecasts.

“We go up and see this expansive drought-stricken range land and know that unless we get the needed precipitation over this winter and spring, our wildlife is going to be faced with some big challenges in the coming year,” McKee said.

Future study of Nevada habitat is planned to guide work in places where conflicts cause the most harm.

Biologists place hope in data-driven collaborations to predict and anticipate further catastrophic change. With the new streamlined workflows providing the ability to compare mule deer reaction to changing conditions, NDOW hopes to engage with other states and stakeholders, including university researchers, to pinpoint causes of decline.

“We don’t even know what changes we’re going to be looking at in a couple of years,” Schroeder said. “But now we can ask these landscape-scale questions.”

Read more about the benefits of rapid data collection of field observations.

August 4, 2021 |

August 31, 2021 |

January 4, 2022 |