April 22, 2021 |

January 4, 2022

With its waterfalls, geysers, and wide variety of wildlife such as bison, cougars and grizzly bears, Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming remains one of most beloved spots in the US, drawing nature lovers from around the world to gaze at its wildlife and astonishing vistas.

These breathtaking landscapes and free-ranging wildlife are protected and managed to minimize impacts of visitors who come to experience the awe of nature and wildness. But within and beyond protected federal lands, roads usher millions of visitors and vehicles through wildlife habitats and across migration and movement corridors, creating the potential for dangerous intersections of traffic and animals that threaten both motorists and wildlife.

For instance, along the US-191 corridor north of Yellowstone, toward the Big Sky ski area, traffic increased 38 percent from 2010 to 2018 and animal-vehicle collisions now account for roughly 25 percent of all crashes.

The problem is not isolated. Across the US, car and truck crashes with animals take the lives of an estimated 1.5 million large mammals a year. Those crashes also injure 26,000 people and kill about 200 people annually. Additionally, there’s up to $8 billion in damages each year.

The urgent need for the collection of standardized data and map where wildlife-vehicle collisions occur has accelerated recently with the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law; it includes $350 million to build wildlife road crossings, provided there is data to support and guide the decisions.

Researchers are plotting the collected roadkill observation data on smart maps and conducting analyses using a geographic information system (GIS). The National Park Service (NPS) and US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) have worked to create the ROaDS tool and analyze the data in partnership with the Western Transportation Institute (WTI) at Montana State University.

Collecting uniform wildlife collision data across the nation has always been a problem with lack of resources and thousands of miles of roads to be monitored 24 hours a day for roadkill incidents.

The need for action increases as human populations continue to encroach on the natural habitat, vehicle traffic increases, and the climate crisis and wildfires force herds to seek greener pastures and cleaner water.

“It’s tough on wildlife because beyond protected public lands, we just keep expanding our own footprint of development across the landscape,” said Amanda Hardy, a wildlife ecologist with NPS. “Understanding where wildlife live, and where they’re moving to and from, and protecting those areas amid the matrix of development is key to their long-term survival and our coexistence with wildlife.”

When people download the ROaDS tool on a mobile device, they can collect roadkill observation data that can guide mitigation measures needed to reduce these conflicts.

“Identifying wildlife migration corridors where they intersect with our transportation corridors, and where we might have wildlife-vehicle conflicts is going to be really important going forward,” Hardy said. “Making sure we put those protections into those areas is absolutely key … But it starts with the data.”

The ROaDS tool allows scientists, park rangers, concerned residents, law enforcement, nonprofit groups, and students to collect key information that contributes to implementing solutions that have been long hampered by insufficient data collection.

Two projects around Yellowstone have been drawing significant interest among volunteers who want to help document vehicle-wildlife collisions. Using the ROaDs tool, they can note GPS coordinates, time of observation, date, and wildlife species observed, among other information.

“We have hundreds of wildlife observations recorded so far on the two highways we are monitoring in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: Highway 191 (west of Yellowstone), and Highway 89 in the Paradise Valley (just north of Yellowstone). So, there’s been quite a bit of use at least by a handful of dedicated people who are going out and doing this on a regular basis,” Fairbank said.

Fairbank said the aim is to provide usable information so planners can select the appropriate type of wildlife crossings and build them in the most important and effective locations. “The goal is to provide information for transportation planning that accommodates safe passage for both wildlife movement and human movement, and that can actually save money in the long run by reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions”

To make matters even more urgent, the number of collisions in the US has risen by 50 percent over the past 15 years, even while the total number of crashes has remained relatively stable over that time. That growing statistic often means even more stress on the survival of species that may already be threatened or endangered.

Given that many wildlife-vehicle crashes are not reported to law enforcement or insurers, the Federal Highway Administration estimates the actual tally is between 1 million and 2 million wildlife-vehicle collision incidents in the US each year; however, ROaDS can help clarify the number.

The ROaDS tool also reflects the focus on endemic species in an area or to fit the purpose of a diversity of groups collecting slightly different types of data. “One interesting group is the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes,” said Mathew Bell, research associate with WTI. “They started using the ROaDS tool, and we are actually going to look at their data and how it compares to Montana Department of Transportation’s data…in the same road sections” of US Highway 93 where it crosses the Flathead Indian Reservation.

By taking samples from different groups, it may be possible to produce better estimates.

“If nothing else, it definitely increases interest and awareness of the problems,” Bell said. “Living in Montana, we know to watch out for wildlife, but as you get the public involved in these things, they start to acknowledge how many are actually getting hit, how much wildlife are dying, and the safety concerns as well.”

Although the work around Yellowstone National Park tends to focus on larger mammals, a nonprofit group is tracing movements and tracking mortalities of desert tortoises, a threatened species listed under the Endangered Species Act, in the Mojave Desert.

It’s not just the large mammals that are at risk, although the larger ones pose the most danger to drivers and passengers in the event of a collision. Many smaller species may also be injured or killed, potentially upsetting the balance of nature in the area. Smaller species can also cause crashes, as people swerve or stop for all sizes of animals.

That is often the case in areas managed by the USFWS, said Vincent Ziols, manager of the Transportation Safety Program for the USFWS National Wildlife Refuge System.

“We may not be dealing with huge collisions that get a lot of news coverage…but various species on our refuge units are getting hit,” Ziols said. “It’s very difficult to protect the integrity of complex ecological systems when there may be a dozen or so species at risk of becoming roadkill at one given point.”

According to the Federal Highway Administration, there are 21 federally listed threatened or endangered animal species in the US for which road mortality is documented as one of the major threats to their survival.

The ROaDS tool allows observers to attach a photo of the deceased animal to the data-collection form, improving positive identification and documentation of mortalities of rare or at-risk species that are important to recovery efforts.

“ROaDS will go far to highlight the need to protect all wildlife from our nation’s roads, and not just in those areas that have already received attention from the public,” Ziols said. “Those in conservation can use this tool to address these issues all over the nation for both big and small animal species.”

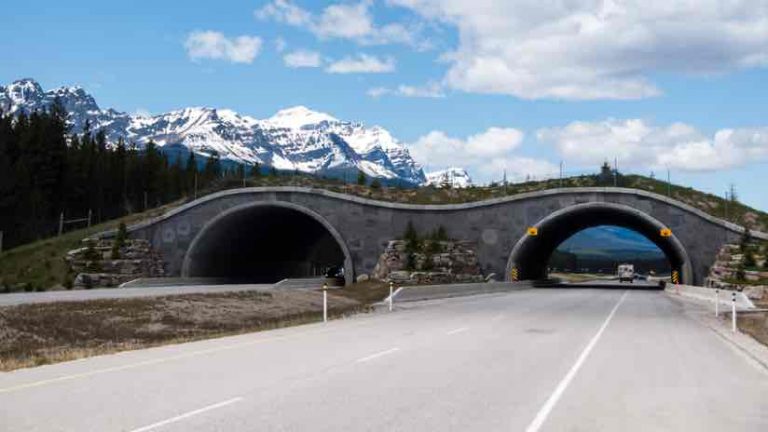

In Canada’s Banff National Park, mitigation measures and a series of wildlife crossings, including both bridges and tunnels allowing wildlife to cross over and under roads, have reduced collisions between vehicles and all species wildlife by more than 80 percent.

Data shows that the number of elk and deer, specifically, hit by vehicles has been reduced by more than 96 percent in Banff National Park. It’s an example of how a concentrated effort supported by clarifying research and strong funding can produce outstanding results to benefit both driver safety and wildlife survival.

It’s also a reminder that the $350 million contained in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law has the potential to fund many safe passage projects for animals in the US, and these will have the most impact where data shows the highest wildlife road mortality.

“You probably aren’t going to get one of those grants unless you come to the table with the information that justifies why you would be putting an investment at a given site,” Hardy said Hardy. “It’s really exciting to see that they’re providing that type of funding for those projects. But it starts with data.”

Ultimately, the ROaDS tool enables agencies and citizens to collect the data needed to effectively invest in measures to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions.

Learn more about how GIS is used to guide environmental and wildlife management.

April 22, 2021 |

October 3, 2019 |

September 18, 2019 |