In the wetlands of South Africa’s east coast, in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, just a short distance from the warm Indian Ocean, lives an amphibian so small it could perch on your thumbnail.

Barely 2.9 centimeters (1 inch) in length, the Pickersgill’s reed frog is one of the most endangered amphibians in the world. Despite its tiny size, this creature plays an important part in the rare coastal ecosystem it calls home.

If the Pickersgill’s reed frog and other frogs in its community disappear, there would be ripple effects. Mosquito populations would explode; insects that damage crops would go unchecked; birds, reptiles, and fish that rely on frogs for food would suffer. And people of KwaZulu-Natal would lose one of the clearest signs that something is wrong in their water systems.

Thanks to science, dedicated conservationists, and geographic information system (GIS) technology, this little frog has a second chance.

Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife is the provincial conservation authority for KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Tasked with protecting biodiversity and managing 87 protected areas, Ezemvelo works with partners such as the Endangered Wildlife Trust and Johannesburg Zoo to preserve important habitats, support ecotourism, and enhance community uplift.

Before using GIS, Ezemvelo lacked a reliable way to track historical and current locations of the Pickersgill’s reed frog. Lacking this knowledge, protecting the frog’s habitat proved difficult.

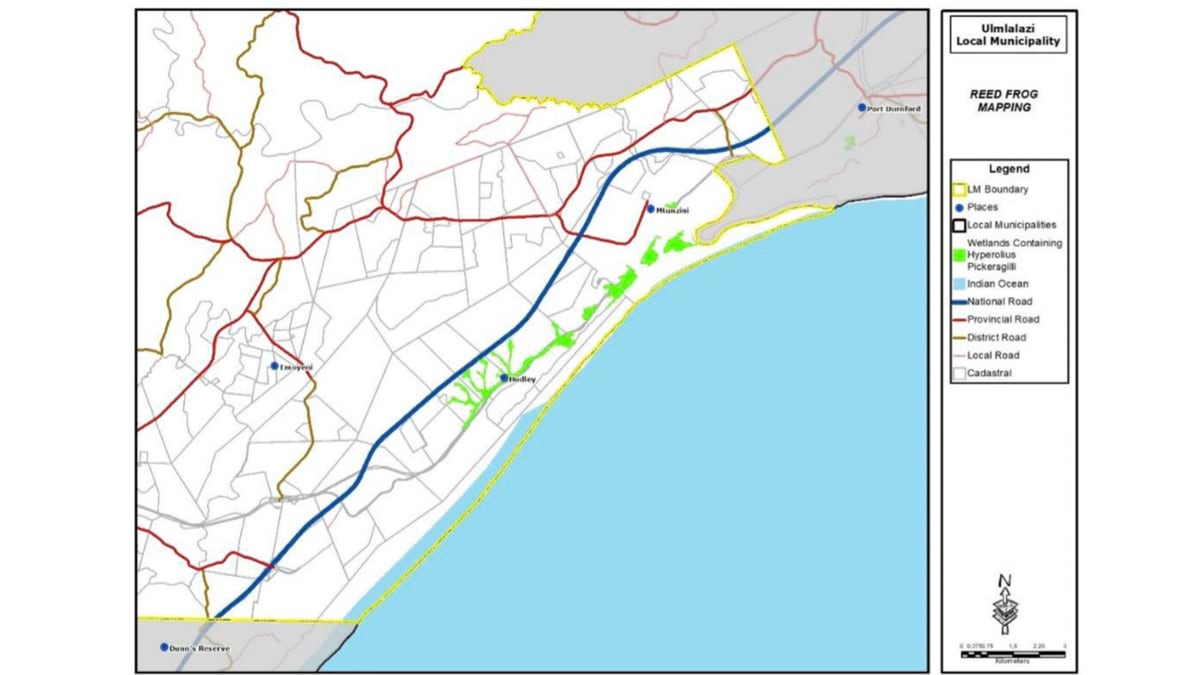

That changed in 2020 when the Ezemvelo conservation team began using GIS to map frog populations, model potential habitats, and track hazards and vulnerability.

“Without GIS, we wouldn’t be able to describe how land-use changes were affecting the frog’s habitat, and the risk the frog population faced,” said Bimall Naidoo, GIS technician at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife.

Adrian Armstrong, an animal scientist at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife added, “This is the first time a frog species in KwaZulu-Natal has been included in land-use planning decisions in a range-wide formal systematic process. Using the analytical and cartographic tools available on the ArcGIS platform has facilitated data and map sharing which has positively influenced the land use planning in some municipalities.”

Naidoo and the team of amphibian specialists also use GIS to identify critical corridors that connect isolated habitats. These corridors allow for movement, breeding, and genetic diversity, which is essential for long-term survival.

The Pickersgill’s reed frog is found only within 15 kilometers of South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal coastline. It thrives in warm, humid wetlands thick with coastal vegetation—habitats that are shaded and filled with stagnant water ideal for breeding. But this narrow environmental range makes the species extremely vulnerable.

As nearby cities sprawl and agriculture expands, the KwaZulu-Natal wetlands have been drained, paved, burned, and polluted. Invasive plants outcompete native vegetation. Roads cut through once-connected breeding grounds. Fires, pesticides, chemicals, and sewage runoff threaten what little habitat remains.

But conservationists created GIS maps that identify fragments of suitable habitat with precision. By layering data—including rainfall, vegetation types, frog sightings, and wetlands—they created a comprehensive map of what the frog needs to thrive.

Some well-intentioned conservation efforts over the years have had unintended consequences. In one instance, the frogs bred from a polluted wetland couldn’t reproduce because of chemical exposure. In another, they were released near developed areas but the amount of water channeled off roads and buildings during severe storms was too great and flooded them out. Others stayed put because the surrounding landscape was too dry and built-up, exposing them to risk if they tried scouting for a new home. Busy roads are a death trap for these tiny creatures.

“The frogs won’t travel through areas that don’t have humid cover,” Naidoo said. “This isolates the populations, hindering the dispersal of offspring and genetic exchange between populations.”

As populations become more isolated, their numbers shrink. That leads to inbreeding and a higher risk from disease, which makes them even more vulnerable.

Frogs like the Pickersgill’s reed frog are known as indicator species—nature’s alarm bell that signals when an ecosystem is in trouble. Because they take up water through their skin and depend on clean water, frogs are among the first to suffer from pollution or environmental change.

According to a United Nations report, one million species are at risk of extinction. Amphibians face the most challenges. More than 40 percent of frogs and toads are threatened compared to 33 percent of reef-growing corals, which are the next most-vulnerable species on the list.

“Frogs are sensitive to changes in their environment, such as pollution and habitat destruction,” Armstrong and Naidoo said. “Their presence tells us how healthy the ecosystem is. So, if the calling stops, beware of your water.”

Maps and other information to protect the Pickersgill’s reed frog are now included in local land-use planning. Several municipalities—including King Cetshwayo District, Ilembe District, and Mandeni Municipality—use these resources in their planning to guide development in a way that safeguards the frog’s habitat.

“When targeted conservation began in 2011, the Pickersgill’s reed frog was only known to be in about nine square kilometers of habitat,” Armstrong said. “Today, they’ve been found in over 30 square kilometers.”

In 2017, the South African government adopted the Biodiversity Management Plan for Pickersgill’s Reed Frog, making the species’ protection an official part of regional conservation strategy.

The once-overlooked frog has become a symbol of what’s possible when local leadership, partnership, cutting-edge technology, and strong conservation strategies come together. A species once thought too small to find, and too far gone to save, now represents resilience and innovation.

The work isn’t over, but Ezemvelo and the amphibian community can hear progress. The chorus of tiny frogs calling out from the wetlands of KwaZulu-Natal has gotten louder. This song of survival gives the conservationists purpose and hope as they continue to combat habitat loss and pollution, restore habitats, and raise awareness of the Pickersgill’s reed frog’s precarious plight.

Learn more about how conservationists use GIS to restore habitat and protect biodiversity.