December 5, 2019 |

February 3, 2022

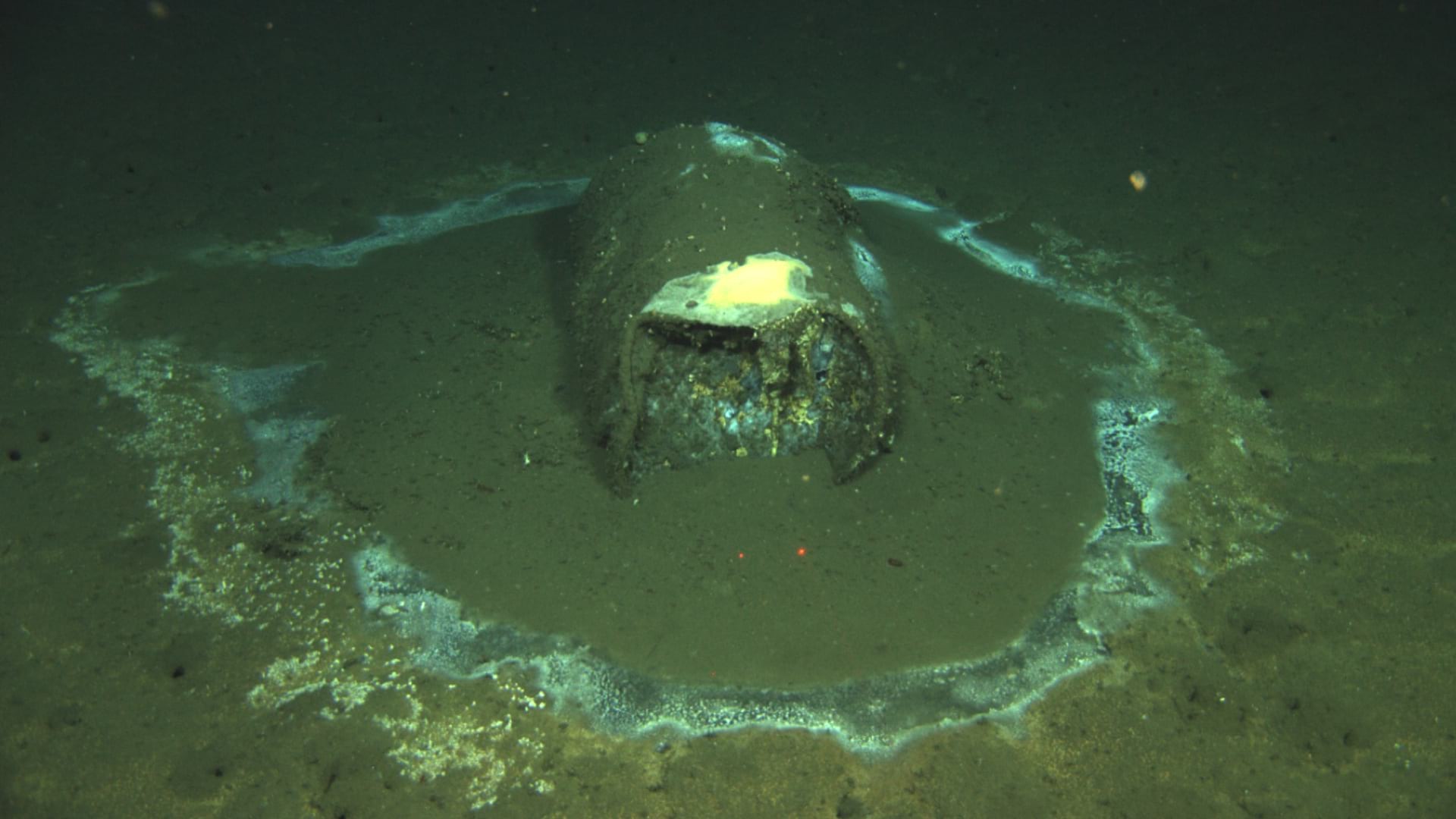

The smell of oil hit early morning beach walkers in Huntington Beach on Sunday, October 3. The cause: tens of thousands of gallons of crude oil had leaked from a rift in the underwater pipe leading from an offshore rig. Lovers of Southern California beaches reacted with alarm, and members of the nonprofit Surfrider Foundation responded.

Within a week, the Surfrider Foundation had registered 10,000 volunteers who were directed to the geospatial crowdsourcing Surfrider Tar Ball Reporting App and could start adding pictures and dropping pins where onshore oil removal was needed. Built using geographic information system (GIS) technology and with help from developers at Esri, the app became “a great way to harness energy from the local community,” according to Eric Laughlin, a public information officer for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “It was more efficient than receiving individual reports.”

As volunteers-turned-citizen-scientists used the app to comb beaches to pin tar balls to the map, the US Coast Guard launched vessels with skimmers to gather as much oil as possible before it hit the beach. Biologists with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife deployed floating booms to keep oil out of wetlands and assess environmental damage. Responders from Orange and San Diego counties donned hazmat suits to gather the spilled oil and tend injured wildlife.

“One of the reasons you want to keep oil and tar offshore is that it’s really difficult to clean up without doing greater environmental damage—it’s like getting chewing gum in your hair,” said Pete Stauffer, environmental director at Surfrider. “Because the ocean is very dynamic—with wind, currents, and swells constantly changing—it’s hard to predict when, where, or how much oil will be washing up.”

Once the oil did wash up on shore, the app made it possible to see exactly where. Response teams could view the damages holistically and better understand the bigger picture of shoreline impact. “We were able to follow the spill because of reporting through the app.” said Dr. Chad Nelsen, chief executive officer of Surfrider Foundation.

More than 1,800 professional responders were involved during three months of cleanup after the spill. Surfrider volunteers added thousands more observers to help pinpoint ecological damage.

Cleanup was officially declared complete on December 29, 2021. Researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s Office of Response and Restoration are now creating a thorough environmental impact report. The study will draw on observations to determine damages and hold the polluters accountable for restoration costs.

The members of Surfrider will be monitoring restoration plans and mitigation measures to see the shore restored. “It’s both shocking and expected, because infrastructure associated with oil drilling fails regularly,” Nelsen said.

The oil spill highlighted problems with aging offshore drilling infrastructure. While there hasn’t been a new offshore platform built off the California coast since the mid-1980s, there have been federal proposals to add more. The city council of Huntington Beach had been slow to call for a moratorium, but after this spill they saw the impact and passed a resolution asking for a halt to it.

“With this oil spill in such a highly populous place, with beaches that are so heavily used, it really raised awareness,” Nelsen said. “Drilling poses threats to the health of our coasts, which are a huge economic engine for Southern California.”

The Surfrider Foundation got its start in 1984 after surfers in Malibu fell ill due to exposure from pollution by a wastewater treatment plant up the watershed. At the same time, a new harbor built in Dana Point meant surfers lost a great wave there. The 1984 Olympics took place in Los Angeles too, and surfers saw how much respect athletes in other sports were getting.

“There was this general sense that the surfer ecosystem was being abused and nobody cared,” Nelsen said. “We realized that if we want to surf in clean water and protect our surf spots, we needed to get active.”

Now, the organization advocates for conservation and rallies local chapters to conduct cleanup operations. In addition to oil spills, the group’s advocacy focuses on reducing plastic pollution, stemming sea-level rise that threatens to drown favorite surf spots, and curbing ocean acidification which is harming coral reefs.

Moving forward, Stauffer anticipates more applications of geospatial technology to address their concerns and empower citizen scientists. “We definitely want to use the app again when the next oil spill happens. I hate to say when but that’s just the reality. We also hope to develop more crowdsourcing tools that allow people to take action and make a positive impact on our environment.”

Learn more about the Disaster Response Program at Esri.

December 5, 2019 |

June 21, 2021 |

May 10, 2021 |