January 19, 2023 | Multiple Authors |

April 23, 2024

A Tennessee State Parks ranger uses the One Smart Park app to record observations at Harpeth River State Park. (Image courtesy of Tennessee State Parks)

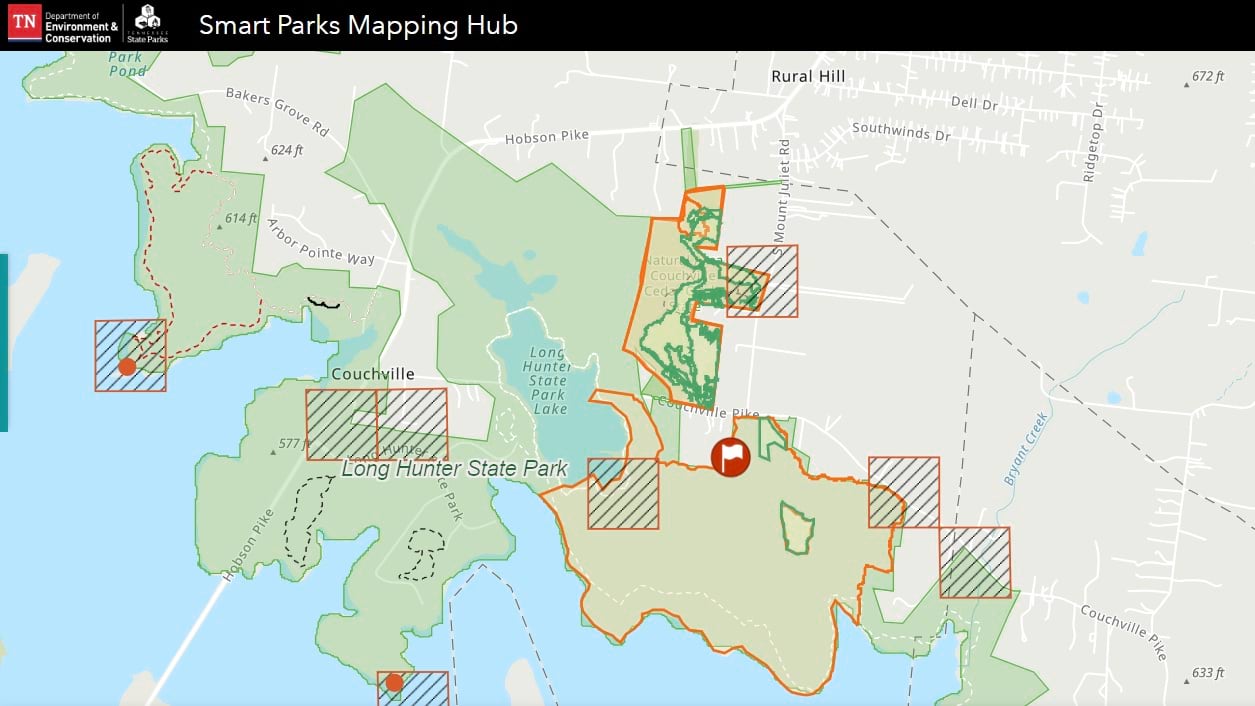

In Tennessee, a state park is never more than an hour’s drive away. The state’s 57 parks and 84 natural areas offer residents and visitors year-round, no-cost access to lush forests, scenic trails, and idyllic bodies of water. Rangers manage all the diverse amenities, management activities, cultural resources, flora, and fauna using the One Smart Park map-based application.

“The rangers are the experts,” said Leah Fuller, a geographic information system (GIS) specialist with the Tennessee State Parks Division of Strategy and Support. “We listened to their needs and frustrations, and then built out a platform to fit those needs.”

Fuller worked with conservation GIS manager Andrew McDonagh using GIS technology to develop One Smart Park. The application contains 15 data layers including park boundary reviews, trail assessments, natural history, asset management, invasive species location and treatment, and prescribed burn planning.

Rangers and park managers can view all the data in one place and add new information for shared, real-time situational awareness. The app serves 290 staff who share knowledge across the state.

“We make applications that every state park uses,” McDonagh said. “Everything that state parks do, we put into GIS so the park rangers can see it on the map.”

When new rangers are hired or employees transfer to another location, One Smart Park gives them a comprehensive view of their new park. Those in the field can easily orient themselves to the new area and answer visitor questions for information like the location of park signage, boundary markers, or the nearest trailhead. With numerous seasonal staff members and park employees migrating from one park to another, this expedites onboarding and allows rangers to be fully operational right away.

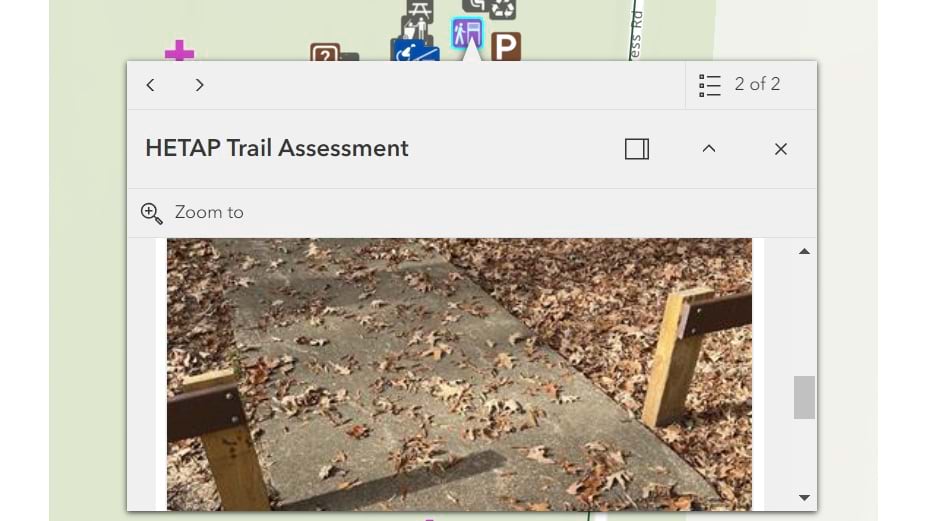

The creation of One Smart Park was inspired by park rangers’ dissatisfaction with data accessibility. For example, the data from an in-depth inventory of state park trails from 2016 to 2019 was sent to the Tennessee State Parks central office but was not shared among the parks. A limited number of licenses to view and use the data, lack of developed GIS editing applications, and a static rather than a dynamic approach to inventory made the large effort less valuable.

“The rangers thought the assessment was going to help them get the resources to repair trails,” McDonagh said. “It didn’t work out . . . and park staff didn’t have a way to see that data again.”

When One Smart Park launched in 2022, 200 rangers were empowered with the ability to review, edit, and utilize historical information for all parks, including results of the trails assessment. Rangers now use data-driven maps and preconfigured mobile forms to locate park assets, add markups and notes about current conditions, and share findings.

In addition to enriching park management strategies, shared situational awareness across GIS has improved the relationship between field teams and the Tennessee State Parks central office. Rangers feel empowered, while the state park system benefits from better operational efficiency.

“Rangers have been given back the tools for natural resource management, which hasn’t always been one of their primary roles, and leadership is really supporting that,” Fuller said.

Specialists from different divisions within Tennessee State Parks work with the GIS team to design maps and mobile forms for data collection.

When park rangers asked for a data layer to support invasive-species management, McDonagh and Fuller sought guidance from experts at the state’s natural areas division. Biologists provided lists of the species to manage, enabling rangers to coordinate their approaches.

One invasive insect, known as the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), has killed large swaths of hemlock trees across Tennessee in recent decades. Several parks are using predator beetles and chemical treatments to control HWA populations. With the help of GIS, park rangers can take a more strategic approach and collaborate with nearby parks, evaluating treatment method success rates.

The invasive-species management layer of One Smart Park has searchable menus with both scientific and common names, as well as a feature to record treatment techniques and the area affected. The app tracks the progress of treatments and monitors changes in species’ growth or decline.

Prescribed burns are similarly monitored, but on a larger scale. Planned fires are used to clear fallen trees, manage plant disease, prevent wildfire, and restore ecosystems. State parks staff can document prescribed burns and wildfire in One Smart Park, attaching burn plans and calculations for acreage and fire line perimeter distance.

“I use GIS and One Smart Park on a daily basis to map our prescribed fire plans, contributing significantly to our conservation efforts,” said Eric Collins, park ranger at Seven Islands State Birding Park. “Using these tools has transformed our approach, making each prescribed fire an efficient and impactful step towardsenvironmental preservation.”

Fuller, who is responsible for creating and maintaining all state park maps—both paper and digital—says that One Smart Park has been instrumental in helping her keep park information up-to-date. Although she may not be contacted each time a new trail or splash pad is added to an individual park, GIS lets her see changes in real time.

“I can look at One Smart Park and see where the new asset is located because the rangers have already dropped a point,” Fuller said. “Then, I can add it to the park map super easily.”

Rangers can track asset conditions to alert managers about assets that require maintenance or repair, such as park signs. If a ranger notices a sign that needs to be replaced, they can capture a photo of it and link it to the sign’s location in One Smart Park, along with a file containing the specifications for a new sign.

“It’s like a living inventory,” Fuller added. “We’ve invested in a system that allows these assets to be managed over time.”

These detailed maps also aid in emergency response. If a ranger is asked to assist on a search and rescue mission, they can quickly identify where the cliffs, waterfalls, and other potentially dangerous areas of the park are located.

“We often find ourselves on a search and rescue in a far-flung area of the park,” said Jason Reynolds, a park ranger at South Cumberland State Park. “To help with our response time and our plan of action, we’ve started to use the ArcGIS Field Maps app, in which we’ve preloaded all of our access roads and rescue points.”

As the scope of GIS in Tennessee State Parks has widened, so too has understanding of park ecology and inspiration to manage these natural assets better. Rangers and managers can visualize what teams from other parks are working on and hone their own efforts. And leadership has a holistic view of the projects and positive outcomes.

“I think our central office is finally seeing, ‘Oh, this is what GIS can do,’” Fuller said. “The office can see the vision Andrew and I have always had.”

Learn more about how parks and recreation departments use GIS to enhance park experiences.

January 19, 2023 | Multiple Authors |

February 25, 2021 |

July 14, 2022 |