July 12, 2022 | Multiple Authors |

January 19, 2023

“What is common to the greatest number gets the least amount of care,” Aristotle stated in 350 BCE. In 1968, ecologist Garrett Hardin expanded on this idea, coining it “the tragedy of the commons.” Hardin argued that, when it comes to using earth’s natural resources, individuals will always act in their own best interest.

Trust for Public Land (TPL) promotes the benefits of the commons, combating the defeatist sentiment of Hardin’s statement that all shared spaces are overused. TPL passionately works to catalyze communities to be healthier, more livable, and more connected through parks and public lands.

While the tragedy of the commons may help explain some negative results of modern life—unsustainable development, air pollution, carbon emissions, depleted water supply—TPL uses data to show how parks and public lands not only mitigate these harmful outcomes but also create shared, positive outcomes. TPL uses conservation economics in a recent report to prove that public parks—an often underfunded public good—provide a myriad of benefits that have monetary value.

To publish The Economic Benefits of Parks in New York City, a team of economists, specialists, and research partners used geographic information system (GIS) technology to measure the fiscal impacts of city, state, and federal parks within New York City. The report explains how parks lower health-care costs for people who exercise there, provide natural air and water filtration, increase property values, and promote tourism while serving as a place for people to connect with nature.

The report—the first of its kind to study the city’s integrated park system—reveals that policy makers have extraordinary financial incentive to increase funding for the creation, protection, and maintenance of public parks, because parks provide an economic engine for the city.

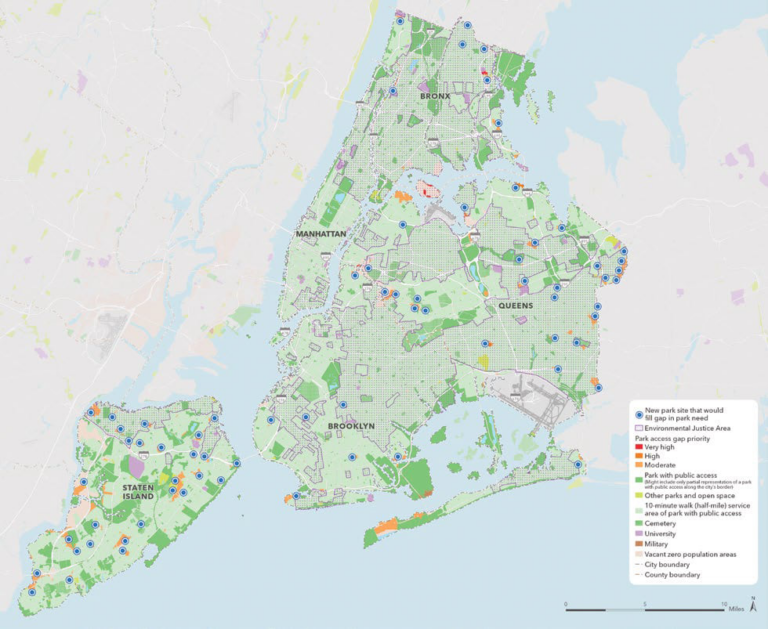

TPL is a national nonprofit that works with communities to create parks and protect land. For more than 10 years, TPL’s ParkScore index has used information about access, amenities, investment, acreage, equity, and a GIS model to rank how well the 100 largest US cities are meeting the need for parks. Currently, 99 percent of New York City’s nearly 8.5 million residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park.

ParkScore measures accessibility, but TPL needed a way to measure the intangible benefits that come from park proximity. An understanding that the economy, social systems, and the natural environment are intertwined prompted team members to ask—How can the public health advantages be quantified? How can the benefits of the natural environment be valuated?

There’s a growing global interest to put a value on ecosystem services—the many life-sustaining benefits we receive from nature—but nobody had made these calculations across New York City’s urban park system.

“We wanted to make sure people understand that, in addition to having a nice place to play and a break from the urban experience that a park offers, there are other indirect benefits in relation to air quality, stormwater management, and wildlife habitat. We wanted to prove that we can make the most of limited funding and meet multiple needs with parks, because they’re a big part of what makes a community healthy,” said Mitch Hannon, TPL GIS program director.

The project was no small task. New York City maintains more than 48,000 acres of parkland across the city’s five boroughs, making parks a valuable public asset and a critical part of the city’s infrastructure. New York State also maintains important recreational assets like Shirley Chisholm State Park; the National Park Service oversees iconic places like Liberty Island and Grant’s Tomb; and there are many multi-jurisdictional parks like Governors Island and Hudson River Park. “Valuing ecosystem services and outdoor recreation is a challenge because the information can be so dispersed,” said Jennifer Clinton, TPL senior parks and conservation economist.

To analyze and appraise such a vast resource, Clinton, Hannon, and their partners looked to geospatial tools, such as ArcGIS Business Analyst, which provided location-driven market insights. Business Analyst contains data on consumer behavior, leisure, and business activities in a geographic context, which helped the team estimate how recreation spending contributes to the local economy.

“On a local level, Business Analyst is an obvious tool because of its ability to analyze market potential,” Clinton said. “It gave us a way to figure out how residents were spending their money, how often they’re participating in certain activities, and the estimates of spending in different categories. We were able to articulate data in a way that allowed us to speak to local policy makers in a way we hadn’t been able to before.”

The three sections of TPL’s report—human health, nature’s services, and economic impact—outline billions of dollars in benefits and savings that New York City parks give residents, businesses, and visitors each year. Some of the most impressive figures include the $9.1 billion in recreational value, $2.43 billion in avoided stormwater treatment costs, and $17.9 billion in tourism spending that the New York City park system generates.

“Even though we believe these values are present in our work, we’re always a little blown away by the valuations we find in some of these reports. Billions of dollars are reflected in the work of conservation. It’s a lot more than people would imagine, in terms of environmental services and economic impact,” Hannon said.

For policy makers, the report is timely. The passage of the Great American Outdoors Act in 2020 and the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021, and the introduction of the Community Parks Revitalization Act in 2022, show that parks are a national priority. Communities are well-positioned to use federal funding to reduce the effects of climate change, improve collective health, and boost their local economies by maintaining and creating parks.

The TPL report provides a framework that TPL will replicate elsewhere to quantify the vast potential benefits of parks as well as inspire imagination and motivation to continue and expand park funding.

Because the report’s analysis was limited to the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, it serves as a conservative baseline. The TPL team knows that there was a substantial rise in park use in 2020, because they were among the few places people could escape to. Clinton is hopeful that the increase is sustained and continues to generate value and engagement with nature.

In the months since its publication, The Economic Benefits of Parks in New York City has influenced policy makers’ short- and long-term funding decisions. “Our most immediate need was securing short-term funding for cleaning and maintaining parks that saw record use during the pandemic. But to meet long-term goals of park equity and climate resiliency, we also need to build and maintain new parks. The big structural challenge is finding strong and dependable funding for parks,” said Carter Strickland, TPL’s vice president for the mid-Atlantic region and New York State director.

New York City mayor Eric Adams pledged to devote one percent of the city’s budget to funding public parks and broke ground on 104 previously paused park projects in March. In addition to connecting residents to nature, parks appeal to tourists and give business leaders a reason to establish an office or storefront nearby.

“There’s a dual benefit to parks—they help bolster the economy and they’re essential for residents’ quality of life,” Strickland said.

Strickland, Hannon, and Clinton are optimistic about the role of parks in economic recovery, especially in the wake of the pandemic. Appraising the often unseen but important benefits of these spaces provided a critical foundation for their creation, protection, and maintenance. Hannon said this analysis couldn’t have been done without GIS.

“It’s so powerful to look at a map and see where you need to work,” he said. “It’s not just theoretical. You’re there—right there.”

Read more about how GIS helps plan and maintain parks and open spaces.

July 12, 2022 | Multiple Authors |

February 25, 2021 |

September 11, 2017 |