January 6, 2026

How Utah—America’s Most Urban State—Uses Data to Solve Housing Affordability

When governors face a crisis, they often ask the same question first: “Show me where we are.” In 2024, housing affordability topped state policy agendas. Leaders turned to maps to understand current inventory and identify sites for new units.

Utah faces constraints that make every housing decision critical. With mountains hemming in development and the federal government owning 64 percent of the state’s land, there’s little room for sprawl. But constraints aren’t unique to Utah—every state faces limitations, whether coastal boundaries, farmland preservation, water scarcity, or infrastructure gaps. When easy options disappear, states need strategic choices about where and how to grow.

Utah’s geographic squeeze creates pressure for data-driven decisions. The state wants to welcome the next generation of homeowners. That requires knowing exactly what land is available and which infrastructure investments unlock the most opportunity.

Steve Waldrip, Utah’s senior advisor for housing strategy, describes Utah’s geography bluntly: “Everybody lives in a bobsled chute.” About 80 percent of Utah’s population lives packed into the narrow 150-mile corridor stretching south down Interstate 15 from the Idaho border.

“We’re not a Phoenix or Las Vegas or a Dallas where you can just keep sprawling,” said Dejan Eskic, a housing researcher at the University of Utah’s Gardner Policy Institute. This geographic reality, combined with economic forces, has priced out an entire generation of potential homebuyers.

-

Mountains hem in development along Utah's Wasatch Front, where geographic constraints make data-driven decisions essential for housing growth. New mixed-use development in Lehi combines apartments and commercial space—making efficient use of limited land.

Governor Spencer Cox made housing affordability a signature issue, setting a goal to build 150,000 new housing units, including 35,000 starter homes, by 2028. To counteract these limitations, Utah is pioneering a comprehensive data-driven response that other states are watching. Geographic information system (GIS) technology supports this—from inventorying public lands to mapping infrastructure gaps to tracking permitting timelines—providing the location intelligence that connects policy decisions to real-world outcomes (see sidebar).

A Generation Left Behind

Governor Cox’s ambitious goal requires a map and accurate measurements. The plan coordinates four key players: Laura Hanson, the state’s long-range planning coordinator; Eskic, a university researcher tracking housing economics; Laura Ault, who directs the Utah Geospatial Resource Center; and Waldrip, coordinating policy across agencies. Together, they’re building the data foundation needed to understand not just where Utah stands today, but who’s being left behind.

The wealth gap tells the affordability story in stark terms. According to the Federal Reserve data that Eskic tracks, the average renter in Utah holds $11,000 in wealth while the average homeowner has $400,000. “A lot of that net worth is in the equity of the house,” he said.

This divide reflects a broader generational trend. Anyone born after 1990 faces housing costs that have far outpaced wages, creating the first generation in decades with less wealth-building opportunity than their parents. Buying a first home has become financially out of reach for millions of young adults.

This gap creates the policy questions Eskic examines: What types of housing are being built? And what can people afford? Developers face a bind. They can’t sell high-end homes because, Eskic notes, “the market’s tapped out,” but local regulations often prevent building affordable housing.

The development process alone adds massive costs. Eskic estimates that a quarter of a project’s budget gets spent before construction begins. The entitlement process—getting raw land approved for development—takes 18–24 months in most Utah cities. “Ask any developer in any part of the country and they’ll say they hate that process the most,” Eskic said.

Utah is addressing this by making state-owned land available for development. The Utah Department of Transportation recently announced plans to sell a 2.7-acre vacant parcel in Salt Lake City for affordable housing development. The site, formerly a maintenance facility, will become condominiums targeted at moderate-income buyers. It’s an early example of how Utah turns underutilized public property into housing solutions, part of a broader effort to evaluate state-owned parcels for potential development.

Looking for Opportunities in the Data

For years, housing policy relied on what Waldrip calls “windshield data gathering”—officials driving around making assumptions. “All of our housing discussions are based on who drove what road recently and looked out and said, ‘We’ve got a lot of apartments there, that place is fine,’” he said.

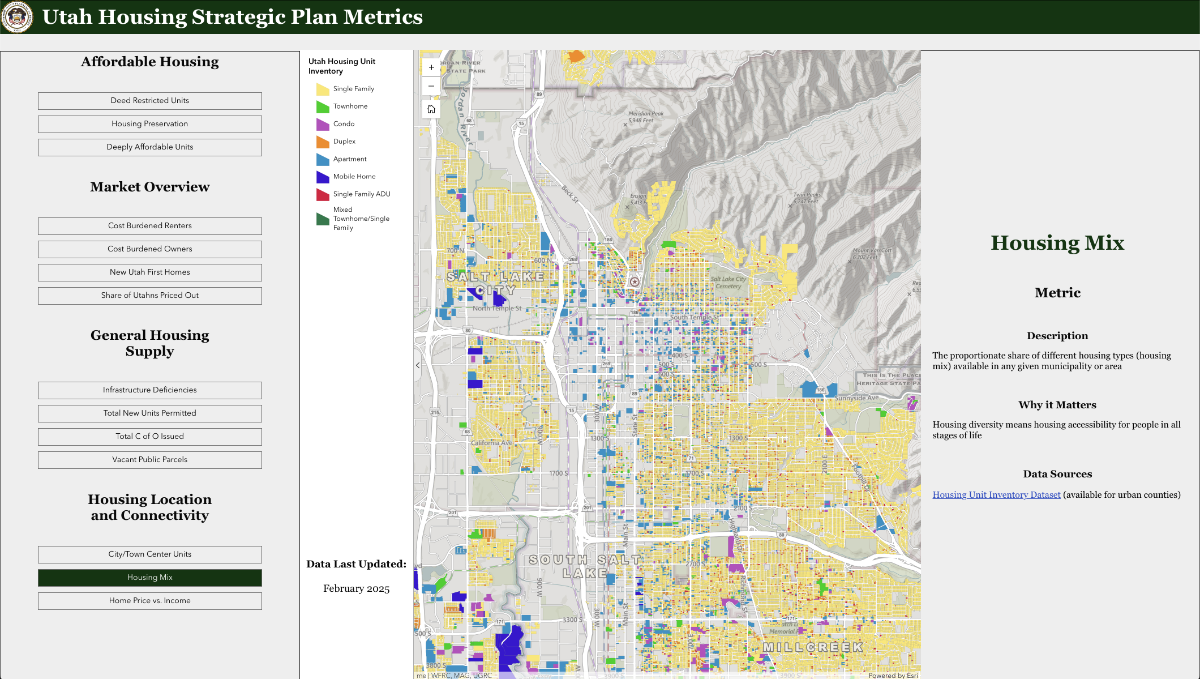

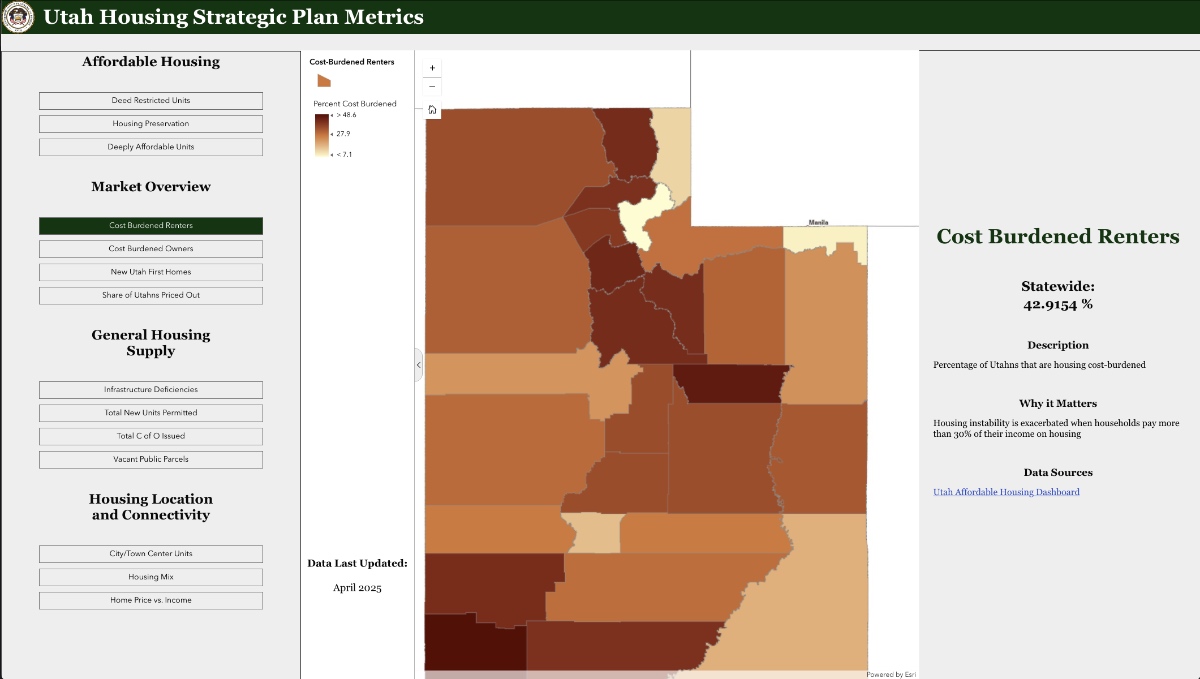

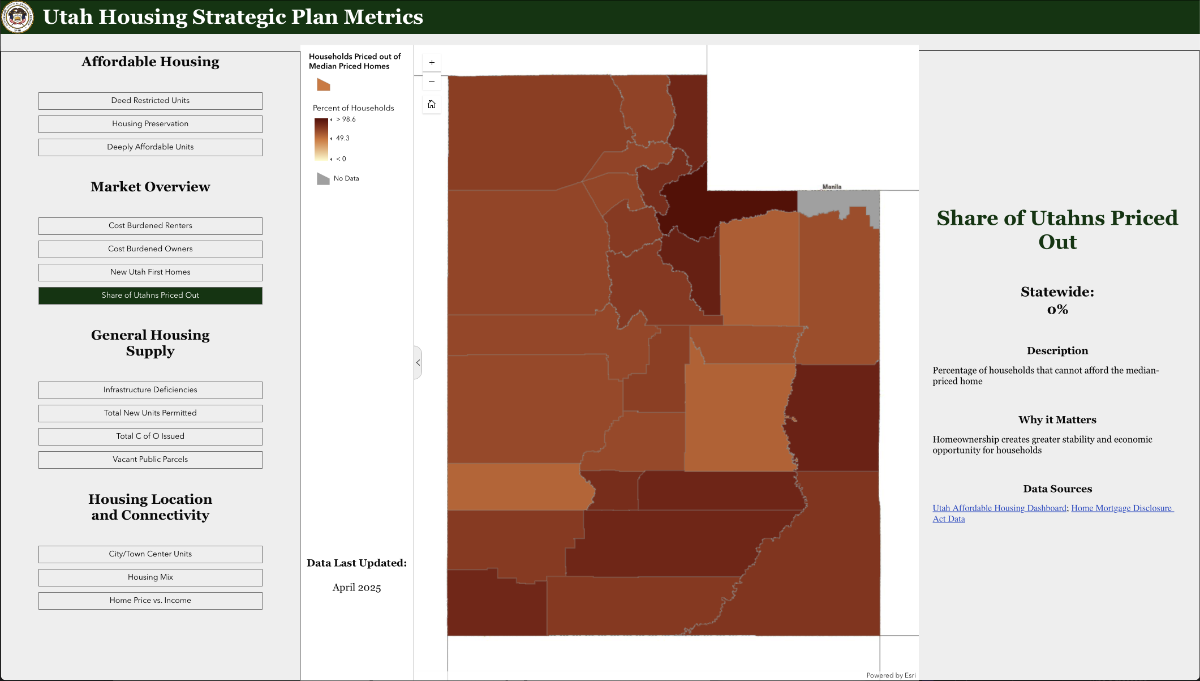

The Utah Housing Strategic Plan Metrics dashboard changes that. Built by the Utah Geospatial Resource Center (UGRC) with Eskic’s team at the Gardner Policy Institute, the web-based tool tracks everything from cost-burdened renters to new construction permits.

UGRC director Ault explains that the dashboard reveals both available data and gaps, reflecting the Governor’s priorities. The dashboard doesn’t hide its limitations—it clearly marks where data exists and where gaps remain. This transparency drives action to fill those gaps.

Hanson calls this revolutionary for long-range planning. “If we can get the data on the map in a common form, then we can argue about the solutions and not the facts,” she said.

The dashboard updates quarterly, tracking progress toward the 150,000-unit goal. As of October, the state had permitted 36,783 units—of which 5,801 are new starter homes—behind pace with three years remaining to close the gap. Eskic says the metrics show some success: rents have dropped while incomes have risen, making housing “a little bit more affordable this year than two years ago.”

The tool tracks both market-rate and subsidized housing production and monitors naturally occurring affordable housing—older properties with lower rents. Each quarterly update brings more precision to understanding Utah’s housing challenge and measuring progress.

This data-driven approach reveals something crucial: housing production isn’t just about zoning changes or construction permits. The real bottleneck often lies in the infrastructure needed to support new development.

-

The "Share Priced Out" view compares area median income to housing costs across every Utah county—revealing in stark red tones where homeownership has moved beyond reach for most households.

The Infrastructure Foundation

Behind Utah’s housing shortage lies the less visible challenge of infrastructure capacity. New homes need water lines, sewer systems, stormwater management, electrical service, and roads. GIS maps these systems—showing where capacity exists, where gaps create bottlenecks, and where investments unlock development.

Waldrip calls infrastructure “a huge hole in our understanding.” The state has detailed road data but lacks comprehensive information about water, sewer, and power networks. Without knowing existing capacity, planning for growth is guesswork. Federal security restrictions prevent water agencies from sharing system maps, even with other state agencies. This creates information silos that hinder coordinated planning.

Hanson describes a common scenario: A city approves 800 new housing units, but the project stalls. The development needs a $70 million water treatment facility—a regional infrastructure investment that would serve multiple future projects. “What city has the money to think that far into the future for big regional needs?” Hanson asks. Without knowing where water lines end, which pipes need upgrading, and where treatment capacity runs out, housing can’t be built.

Hanson’s goal is a 30-year plan coordinating all infrastructure investments—transportation, utilities, and stormwater. GIS overlays infrastructure networks with development plans, showing which projects share needs and where regional solutions make sense. A new water main might also support road widening and enable transit-oriented development. State law already requires station area plans around high-capacity transit, identifying space for 74,000 housing units near rail and bus rapid transit, with eventual capacity for 100,000 units.

Utah is also mapping publicly owned parcels that could support housing—from closed schools to unused staging areas—reducing land costs.

-

Multi-family construction progresses in Utah—the type of higher-density housing that the state's dashboard tracks quarterly to measure progress toward the 150,000-unit goal by 2028.

Building Cooperation Through Data Sharing

Utah’s housing response succeeds because multiple players cooperate around shared data. UGRC serves as the central hub, standardizing information from 29 counties so state planners, local officials, and developers work from the same foundation.

Ault leads this effort, collecting roads, parcels, and address points from local governments and standardizing them.

The challenge varies dramatically by location. Salt Lake County has strong GIS systems. Rural counties might have one employee handling city recorder duties plus multiple other jobs. UGRC bridges this capacity gap.

The state funds technical assistance positions in seven regional associations of governments. These specialists help small communities digitize data and build GIS capacity. “We don’t want to be the ones with the sticks,” Ault said. “We’d rather have a bag of carrots.”

This approach reflects Utah’s collaborative traditions. UGRC has built relationships with local governments since 1982, creating trust that enables data sharing.

Governor Cox’s clear goal for more housing creates urgency and permission for agencies to work differently. After decades of conversations about better data coordination, Ault sees real momentum. “I feel like right now it actually might be happening,” she said.

Transparency is already changing local practices. Cities are streamlining permitting processes. Hanson is piloting detailed tracking with willing cities to measure where delays occur, replacing anecdotes with hard data.

This collaborative approach—combining state coordination, local capacity-building, university research, and transparent data—enables productive problem-solving. “The nice thing about data is there’s no judgment,” Hanson said. “It just is what it is.” When everyone sees the same information, they can focus on opportunities rather than obstacles.

The urgency stems from welcoming back the next generation. Eskic’s research reveals a unique “boomerang effect”—about 25 percent of people moving to Utah were born there, a higher share than any other state. These returning residents seek the communities they remember, but rising costs threaten to price them out. Governor Cox frames the challenge: “What will happen if our kids and grandkids aren’t able to eventually own property and buy a home in this state? We cannot let that happen.”

By building transparent data systems, Utah creates the foundation for strategic decisions that preserve opportunity for those who want to build their lives here.

Learn more about how GIS helps communities develop strategies to provide affordable, accessible, and attainable housing options for every resident.

Related articles

-

July 10, 2025 |

July 10, 2025 |Patricia Cummens |Infrastructure -

March 18, 2025 |

March 18, 2025 |Keith Cooke |Urban Planning Maps Reveal Hidden Housing Realities in Massachusetts to Address an Affordability Crisis

-

May 7, 2024 |

May 7, 2024 |Sophia Garcia |GIS for Good Smart Maps Help Open Tight US Housing Market to Buyers in the Margins