May 30, 2019 |

October 3, 2019

The Governor of Colorado just signed an executive order aimed at protecting wildlife as animals move throughout the state. The order directs the Department of Natural Resources and the Department of Transportation to coordinate efforts to understand migratory patterns and mitigate wildlife-vehicle crashes.

The effort hopes to replicate statewide the success of a pilot project on Colorado Highway 9 that reduced collisions by 90 percent. A combination of wildlife overpasses, underpasses, fencing and wildlife escape ramps on a dangerous 11-mile stretch of road dramatically cut the prior average of 650 accidents per year. The new order seeks to address the 4,000 wildlife-vehicle crashes and $80 million in property damages that arise from such conflicts in Colorado annually.

Wildlife migration fascinates even the most experienced scientists and cartographers. All major branches of the animal kingdom move with seasonal patterns across the plains, throughout the skies, or deep below the surface of the waves.

But for many animals, migration is thwarted by environmental and human-caused challenges including climate change, infrastructure that blocks and destroys migratory routes, and overexploited areas that leave little for animals to forage.

Without protection and proactive conservation—much of it now backed by technology such as GPS tracking and smart maps—migration patterns crucial to species survival could be threatened or lost altogether.

Protecting the Pronghorn

The pronghorn makes one of the longest migrations in North America, and the longest in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The pronghorn herd native to Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming must migrate 170 miles south before the arrival of the deep snow and harsh sub-zero temperatures of winter.

Herd mammals, like pronghorns, follow historic routes, passed along by the mother to their young, until it becomes instinctually ingrained in the animals. Matthew Kauffman, professor of zoology and physiology at the University of Wyoming and director of the Wyoming Migration Initiative, said in an interview with the Smithsonian, these migration routes make up a series of distinct pathways animals follow to survive in highly seasonal climates, like the mountains of Wyoming.

“It takes generations and generations for herds to learn migration corridors,” Kauffman says. “If you wipe out a herd that has knowledge of a specific migration, then you lose all the knowledge that those animals have of how to make that migration.”

Roads cause difficulties in the pronghorn migration by adding dangerous and narrow crossings. As many as 1.5 million wildlife-car collisions happen each year, resulting in 150 deaths and 10,000 injuries, according to the Federal Highway Administration.

Since the early 2000s, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) documented the pronghorn migration with partners from Grand Teton National Park and Wyoming Cooperative Unit at the University of Wyoming. In 2005, conservation teams collected data by placing GPS collars on selected pronghorns to see how tracking could help mitigation.

The GPS collars identified a migration route now known as the “Path of the Pronghorn.” GPS data was added to a migration map to reveal where the pronghorns’ path intersects with a busy section of Highway 191. Data collected along the route helped identify this section of the highway as a threat and barrier to the migration route.

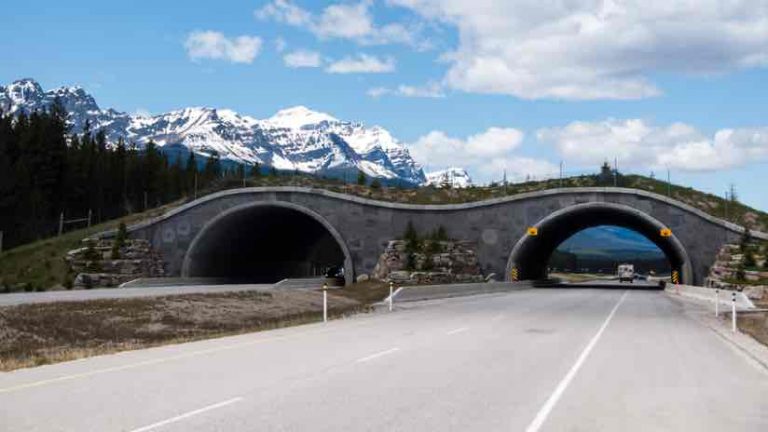

Construction of a new animal overpass crossing structure was completed in 2012 in hopes of preserving the pronghorns’ route and preventing highway wildlife-car fatalities. Field leaders collected pronghorn behavior data as the overpass was being constructed, observing how the animals adjusted to the new migration route.

Since completion, pronghorn and mule deer have adapted to using the migration overpass. The success of this mitigation strategy will help inform efforts for other animals and other routes.

An Osprey’s Improbable Journey

Birds migrate each spring and fall, moving from areas of low to high resources and seeking warmer temperatures. The secrets of birds’ amazing navigational skills are still not fully understood.

The story of one osprey named Julie, who was equipped with a GPS tracking unit, takes readers along for her improbable migratory flight from the Detroit River in southeast Michigan to Florida, the Caribbean, and eventually Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela. Told in an ArcGIS Story Map, the tale follows Julie’s journey and explores why many historical bird habitats remain empty as volunteers work to replenish the environments.

The Scouts of the Sea

Sea migration may be the most mysterious of all voyages, one that still intrigues oceanographers and marine biologists. Most sea animals only ever travel short distances in search of food, breeding grounds, or better living conditions. However, fluctuating ocean temperatures, overfishing, pollution, and destruction of coastal habitats impact sustainability for sea life.

Climate change affects ocean currents and alters entire communities of marine animals, leading many species on long voyages toward warmer water and more hospitable underwater terrains.

Even strong swimmers like the adult whale must adjust course or be carried adrift. Sea turtles provide great examples of orienting themselves in open ocean without being swept to unfavorable areas; while sea lions traverse hard-to-reach places and give scientists more information than they bargained for.

Seals are described as “the scouts of the sea.” Michael Fedak, a seal researcher at Sea Mammal Research Unit at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, has studied seals for over 40 years. Fedak and his team developed a piece of tracking equipment that measures oceanographic data, like salinity and temperature. The tracker is glued on the seals’ fur, which will be shed during their yearly molt, and transmits data back to scientists when the animal breaks the surface of the water.

Through this tiny window of data, scientists begin distilling the complicated life of an animal into behaviors, patterns, and relationships. The seal and its tracker give a more detailed picture of what goes on under the dark ocean waters.

The Future of Migration

As time goes on, the impacts of climate change and overexploitation of resources will force species’ adaptability that will become easier for researchers and conservationists to assess. Mapping animal migration routes is just the beginning of understanding and respecting the creatures with which we share earth’s ecosystems.

John Beckmann, connectivity initiative coordinator for the Wildlife Conservation Society of North America, warned that migration routes, such as the one followed by pronghorns, need to be maintained into the future. But, he warns, there is more to consider.

“If we do a really good job of protecting the migration corridor—build these overpass and underpass structures— but we lose winter range because of natural gas development, then all of our efforts have gone for not,” he said. “We have to be concerned with protecting summer range, winter range, and the migratory pathway to maintain migration.”

Learn the steps a GIS professional takes to conserve a wildlife corridor for a specific species.

May 30, 2019 |

June 27, 2018 |

April 18, 2019 |