Geography is inherently integrative. It weaves together disciplines such as geology and sociology, climatology and economics, and ecology and urban planning into a coherent framework for understanding the world. The geographic approach applies this integrative power through a deceptively simple method: using location to reveal otherwise invisible patterns.

The geographic approach has been a foundational principle of geospatial technology for decades. What’s different now is the reach and urgency of this technology and the problems it solves. GIS professionals are building systems that extend location intelligence to broader audiences through self-service tools. Data that used to take weeks to collect now flows continuously from sensors. Maps update in real time as conditions change. Analyses that required specialized technical skills are packaged as workflows that guide users through valid approaches.

These advances are converging in what can be thought of as a planetary nervous system—a distributed infrastructure connecting billions of inputs to update maps and location datasets worldwide. Cloud integration enables this connection, allowing local knowledge to contribute to a fabric of location intelligence that spans from neighborhood to global scales.

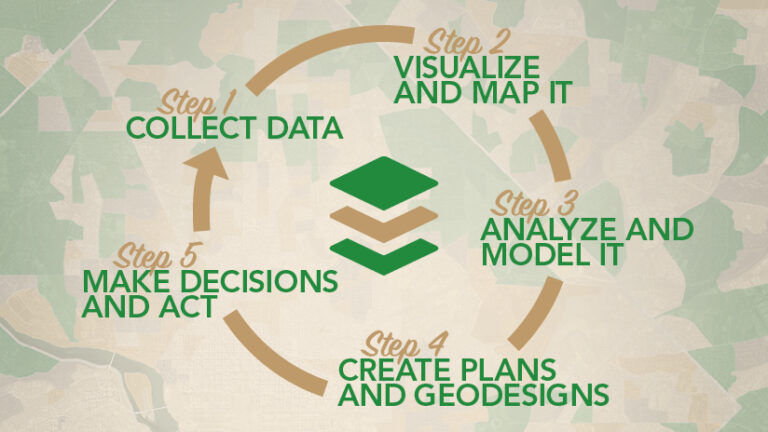

The geographic approach follows a logical progression from question to action and is increasingly understood as a continuous loop rather than a linear path. The five interconnected steps are:

- Step 1: Collect data

- Step 2: Visualize and map it

- Step 3: Analyze and model it

- Step 4: Create plans and geodesigns

- Step 5: Make decisions and act

These five steps form a common framework that can be put into practice across various industries and workflows. Professionals iterate within and between them as understanding deepens and new questions arise. And emerging technology—especially AI capabilities—support this iteration, guiding professionals through workflows, surfacing unexpected patterns, suggesting relevant datasets, and enabling rapid testing of alternatives. The steps have also been transformed by advances in how GIS professionals architect systems, connect data across boundaries, and design for self-service use.

Why revisit this framework now? Because organizations everywhere face a common challenge. Their work is inherently geographic, but systems spring up scattered across departments and get centralized later. Transforming this paradigm requires a culture change—to ensure that data is shared across teams, self-service apps and analysis tools are widely available, location intelligence is embedded everywhere, and leaders anticipate challenges rather than react to them. There must be a willingness to share data with trusted partners while maintaining appropriate governance. Teams must have the patience to build infrastructure systematically rather than chase hype. Leaders must recognize that enduring capability requires years, not months, to develop.

The journey to turn fragmented maps into integrated location intelligence takes time and commitment. The framework that follows can help organizations get started—and persist—in using the geographic approach to continually reveal insights in today’s technological landscape.

Step 1: Collect Data

GIS professionals gather the information needed to understand a situation, from basemaps and imagery to sensor feeds and community observations.

But there’s been a shift from periodic data capture to continuous sensing. This has fundamentally altered both the way data is gathered and what GIS professionals can build. Rather than manually updating datasets, they architect systems that ingest streams from satellites, sensors, mobile devices, and field teams. Cloud integration makes this possible at an unprecedented scale, allowing distributed data to flow into shared infrastructure.

Reality capture technologies are now integral to this continuous flow rather than separate workflows. Photogrammetry, building information models, and drone-captured imagery and lidar point clouds now feed directly into GIS software, providing unprecedented detail about physical conditions. What once required separate projects—conducting aerial surveys, processing imagery, extracting features, and updating maps—now happens as part of a continuous sensing infrastructure supported by AI.

Consider climate resilience planning for low-lying areas. Traditional approaches required GIS teams to compile historical flood data, conduct surveys, and publish static risk maps. Now, GIS professionals build systems where weather forecasts integrate automatically, river gauges report continuously, soil moisture data flows from satellites, and aerial imagery captures changing coastal conditions. These inputs are woven into sensing infrastructure that tracks dynamic processes rather than capturing moments. The GIS expert shifts from data handler to systems architect, connecting diverse streams into coherent, continuously updated representations.

Technology now automates much of what GIS professionals once did manually. This frees GIS teams to focus on higher-value work: designing data architectures, establishing quality frameworks, and ensuring the right information reaches the right people.

Step 2: Visualize and Map

Visualization uncovers spatial patterns, turning data into understanding.

GIS professionals now design interactive environments—living systems that continuously update as reality changes rather than static documents frozen in time. The work involves creating map applications, dashboards, and interfaces tailored for field crews, executives, technical reviewers, and the public.

Digital twins are the most sophisticated expression of this shift. Too often, they’ve been treated as static deliverables—created, handed over, and left to gather digital dust. At their most powerful, they function as living systems that synthesize GIS layers and continuously update as situations change. A city integrating building and traffic data, environmental monitoring, and social metrics can simulate future conditions and model policy impacts with unprecedented precision. GIS professionals design the interface, and planners use it as a workspace—with neural networks automating feature extraction. This allows urban planning teams to work with interactive applications to test scenarios such as flooding projections, the effects of transit expansion, or the impacts of dense development.

GIS professionals now design visualizations that show not just where things are but also how they change. Think of suburban sprawl, shifting coastlines, intensifying heat islands, or traffic flow. Creating time-aware representations requires both technical sophistication and thoughtful design that makes temporal patterns intuitive. The work becomes more about user experience and less about mechanical production.

Step 3: Analyze and Model

GIS professionals use spatial reasoning to generate insights by understanding relationships, testing hypotheses, and predicting outcomes.

Increasingly, they are designing systems that let domain experts conduct sophisticated analysis without having deep technical knowledge of GIS tools. The work has shifted from manual analyses to building frameworks, workflows, and applications that encode best practices and guide users toward valid approaches.

A public health team investigating disease patterns can now use GIS-built applications to select vulnerable populations, measure health-care access, and identify service gaps. The GIS expert designs the workflow and validates the methodology. The health experts apply it to their questions, bringing domain knowledge about which patterns matter and what interventions might help.

Critical spatial problems often involve analyzing connectivity and flow—how things move through infrastructure, supply chains, or ecosystems. Network analysis answers: Where does a problem originate? What path does it follow? What happens if something fails? Systems based in the geographic approach can answer these questions for utilities, transportation networks, and ecological studies.

Step 4: Plan and Geodesign

Geographic intelligence enables GIS professionals to design interventions—determining not just what is, but what should be.

Planning no longer happens in sequential steps (analyze, then design, then review). Thanks to advances in technology, it now consists of iterative cycles where design, impact assessment, and refinement happen simultaneously. Systems show the consequences of design decisions immediately, letting planners understand trade-offs as they work rather than discovering problems later.

A transportation agency designing a new transit line can watch ridership projections, equity impacts, environmental effects, and cost estimates change in real time as they adjust the route. And a single professional can explore design alternatives that once took teams of specialists weeks to evaluate. Move a station, and accessibility scores recalculate instantly. Alter the alignment, and construction cost estimates follow. The system doesn’t just document plans—it helps planners think through implications.

Critically, planning systems increasingly incorporate broader perspectives—not just technical criteria but also community values, equity considerations, and long-term resilience. A geography-based framework helps balance multiple objectives that might conflict, making trade-offs explicit.

Step 5: Make Decisions and Act

The geographic approach converts insight into action—sharing findings, building consensus, and implementing solutions. Implementation often reveals new questions and changing conditions, looping back to the beginning.

GIS professionals now build systems that deliver location intelligence directly to decision-makers in formats suited to their context. The work has shifted from creating individual map products on request to architecting platforms that translate complex spatial analyses for different audiences and use cases, from mobile workers to executives. GIS professionals develop the infrastructure once and design each view for its purpose.

An emergency manager doesn’t wait for a GIS analyst to prepare briefing documents. The operational map that a GIS professional built shows current conditions, team locations, and resource status in real time. As field teams update information from mobile devices, everyone sees the same picture. The GIS team designed the system, configured the workflows, and ensured data flows reliably—enabling decisions based on current information. As the situation evolves, new questions emerge, prompting another cycle.

GIS teams increasingly build platforms for collaborative decision-making, allowing distributed groups to examine the same information, propose alternatives, and work toward consensus. Location intelligence becomes a shared reference point that grounds discussions in specific places and measurable impacts.

From Method to Practice

The five steps of the geographic approach describe a logical progression that forms an interconnected, continuous loop rather than a linear path. Professionals cycle within the steps—collecting new data in response to analysis, refining visualizations based on stakeholder feedback, adjusting models as understanding deepens, and returning to refine the original question based on what they’ve learned. What makes the approach powerful is not only the sequence but also integration and iteration.

Geography provides the framework that holds these steps together. Location is the key that aligns information from different sources, different times, and different perspectives. When public health data, environmental conditions, infrastructure capacity, and social demographics share a geographic foundation, they can be combined in ways that reveal crucial relationships.

The geographic approach remains a method for humans to solve problems together. GIS professionals make the method accessible—creating the infrastructure that lets domain experts apply spatial reasoning to their questions, building workflows that encode best practices, and designing interfaces that make complex analyses understandable. The work requires both deep technical sophistication and a broad appreciation for how different audiences think about and use location intelligence.

What’s different now is the scale and reach at which this approach operates. Complex problems—climate adaptation, biodiversity protection, infrastructure modernization, rapid urbanization—become actionable when teams build GIS platforms that integrate information across dimensions. As GIS work continues to shift toward designing systems rather than operating them, enabling others to analyze data rather than performing every analysis directly, GIS professionals are building infrastructure that extends location intelligence to wherever it’s needed. This doesn’t diminish the importance of GIS expertise or the geographic approach—it multiplies its impact.