September 24, 2019 |

July 6, 2021

Many of Africa’s agricultural endeavors have long been tied to whims of the weather. When it rains, a country’s gross domestic product might soar. When it doesn’t rain, economies suffer. The reliance has been driven in part by the perception that dry, arid Africa has limited water resources. But a new study, years in the making, shows a different reality.

As one South African scientist recently noted, if all the rainfall stopped today and for the next 100 years in Africa, there would still be plenty of water stored underneath the continent’s surface, it just wouldn’t be evenly distributed. That’s why maps are essential in showing which aquifers are vulnerable to rainfall variability.

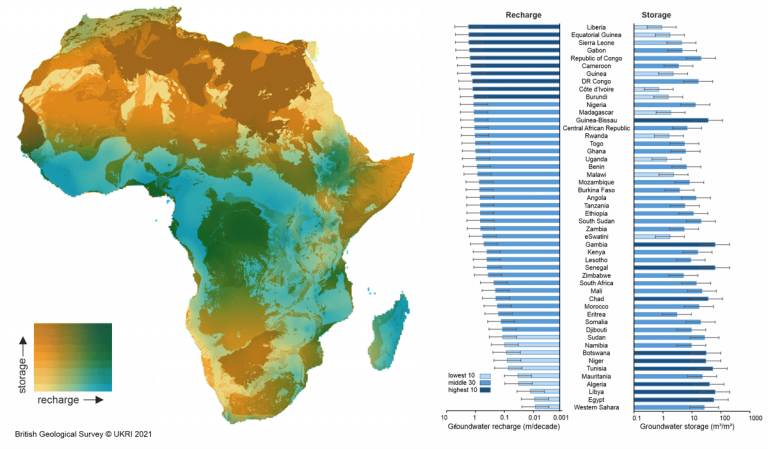

“You can imagine the possibilities,” said hydrologist Seifu Kebede Gurmessa from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa and coauthor of the study. The study, released in February, uses maps from a geographic information system (GIS) analysis to show water replenishment across the continent. It turns out that the vast majority of Africa’s countries either have high water storage or high levels of groundwater replenishment. Five countries have both. Five have neither.

“We say we are prisoners of the rainfall,” Gurmessa said of Africa’s dependence on the resource for agriculture, one of the continent’s largest economic outputs. Little groundwater, proportionately, is used for irrigation currently. “How can we break that imprisonment of seasonality in the rainfall?”

Groundwater use could be a buffer for the stark seasonal swings.

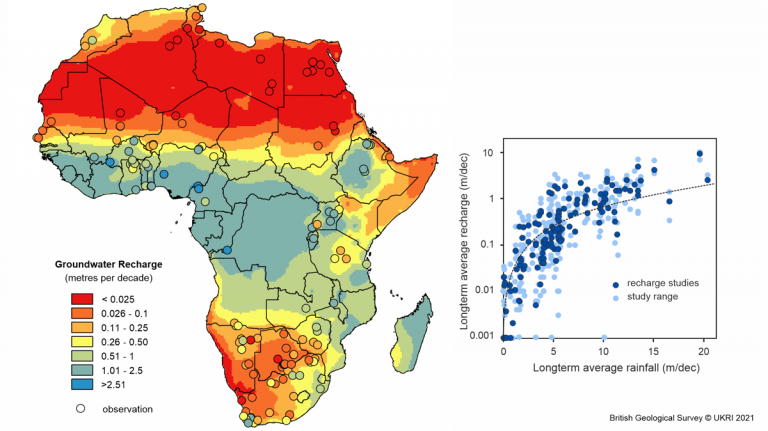

The report, Mapping Groundwater Recharge in Africa from Ground Observations and Implications for Water Security, was led by the British Geological Survey (BGS) and is a sequel to another of the BGS’s groundbreaking studies. Using a geographic information system to aggregate information and perform spatial analysis, the report’s authors brought old data into the present by incorporating factors that impact groundwater recharge including climate, amount of rainfall, the number of wet days in a year, land cover, vegetation health, and soil type.

Nearly a decade ago, the team of international scientists created a map that showed Africa actually had a rather large volume of water hidden and stored underneath the surface. However, the researchers behind the science-shifting report and, later, the BGS’s Africa Groundwater Atlas knew that that was only part of the continent’s water story. Groundwater, like a bank account, depends on regular deposits to balance withdrawals.

Once again, results of the latest research were promising. The study’s authors were able to clearly map, for the first time, which countries had sustainable resources and which ones didn’t. The countries were separated into four color-coded categories: low storage/low recharge, high storage/low recharge, low storage/high recharge, and high storage/high recharge.

“That map is really key in proposing what you can do in different countries,” Gurmessa said.

Most countries had one or the other—high storage or high recharge. Alan MacDonald, the study’s leader and a hydrogeologist with the British Geological Survey, has called it a happy symmetry.

“Still,” he said, “so many people in Africa don’t have any access to safe water.” He and the others involved hope their comprehensive research starts a conversation—just like their first report did in 2012—about what’s possible and what isn’t. For instance, what kind of access to water should be installed in a village if groundwater is plentiful but rainfall is scarce?

While none of the scientists involved contemplates a pumping free-for-all that could deplete groundwater, the report does suggest the continent has been faring better than might have been expected in maintaining a healthy water supply.

“It’s not all doom and gloom. It’s not all bad. In some areas, there is potential for groundwater to provide safe water supplies for many more people than currently have them,” said Kirsty Upton, who oversees BGS’s Africa Groundwater Atlas.

As the report itself states, “With increasing calls to draw from groundwater storage in order to stimulate economic growth and improve food security in Africa, a more nuanced approach to water security is necessary.”

The team’s 2012 countrywide study of the continent’s groundwater conditions—a first of its kind that attracted media attention—led government ministers to hang the study’s maps from office walls. The work also encouraged funding to help 50 Africa-based partners to create a continental groundwater atlas, with data downloaded thousands of times by nongovernmental organizations, governments, students, and researchers. The study’s research and data were also the foundation for the latest groundwater recharge report, which reveals how sustainable the water supply is.

“That was the next stage for us,” MacDonald said. Ten scientists including MacDonald—five in Africa and the others from around the world—promptly got to work, pouring over 320 existing studies to find the most reliable information as well as common themes. They were about to publish in 2017 until MacDonald, noticing that some of the geolocation data for the original reference studies was off, started from the very beginning again to reanalyze the information.

“You want to get this right,” he said considering the importance of the data and how far its reach may be. He recalled a moment, shortly after the 2012 study on groundwater was released, when he met two French mountaineers who had a copy of the daily newspaper Le Monde. “And there was a picture of my maps,” he said. He likened the maps, including the most recent study on replenishment, to a conversation starter.

“If you do get a map that people are really going to look at and use, you want to make sure that you’re giving them information that is useful to them and is a gateway to more information, and not misleading people,” MacDonald said.

The researchers continue to be curious too, looking at additional facets. They’re already developing their next study, looking at the quality—primarily the salinity—of Africa’s groundwater.

For the most recent study, researchers focused on long-term average groundwater recharge rates across Africa from 1970 to 2019. They used 134 existing studies deemed the most reliable, winnowing the total down from 320 and factoring in climate and terrestrial parameters to scale for the entire continent.

The process wasn’t quick, easy, or highly technical. In other projects, MacDonald said, he has used data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) GRACE satellite, which measures water storage changes from space, averaging over a large area (400 x 400 km) to indicate whether an area’s water has been recently depleted.

“But it only gets you so far,” he said, and this time the researchers needed to look in much more detail to understand water renewability on the continent. “It was sheer old-fashioned grunt work.” He and the others went through old files and maps, some found on dusty shelves.

The result of this investigation—funded primarily by the UPGro research program, whose mission is Unlocking the Potential of Groundwater for the Poor—was published in Environmental Research Letters in February.

“It is really a good time to be a groundwater expert in this decade in Africa,” Gurmessa said. “The future also looks more promising.”

Access to and availability of water can affect a whole host of issues, ranging from school attendance to conflict that comes from agriculture workers migrating from one rural area to another, not to mention overall human health. Water is tied to everything in one’s life, he pointed out.

Gurmessa sees the potential for machine learning to predict water quality and described the technological advancements of GIS as being “very useful for illustrating, for depicting, [and] for demonstrating vulnerabilities.”

Eritrea, Eswatini, Zambia, Lesotho, and Zimbabwe are the countries on the continent that have both below average storage and below average recharge levels. This will require measures to carefully manage aquifers, creative ways of storing floodwaters, and efforts in recycling water.

“That is where the map brings an immediate, ‘Wow, what can I do here?'” Gurmessa said. Areas where there’s both high storage and high recharge could be eyed for encouraging agriculture and industry. Those countries include Guinea-Bissau, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, and Angola. The other areas can use carefully managed depletion (ample storage, little recharge) and catchment strategies (little storage, ample recharge).

Getting clean drinking and washing water to more people has sometimes been exacerbated by pump maintenance issues, faulty engineering, and errors in site selection. MacDonald suggested that the latest study could help, showing where there’s less storage but ample recharge and where there’s more storage but less rainfall. MacDonald and Upton note that their information should not be relied on for precise location planning or for determining which types of pumping systems to use; that’s a question for engineers and on-the-ground planners.

“When it comes down to actually drilling a well in somebody’s village, you’ve always got to go out and do the legwork,” MacDonald said. “You’ve got to do some geophysics. You’ve got to site that in exactly the right place so that it doesn’t get contaminated, or that you’re getting the best part of the aquifer.”

MacDonald said they noticed something else interesting in their studies: there may be less overall rainfall for Africa’s aquifers due to climate change, but the intensity of the rainfall has increased. As other resources become more uncertain, groundwater may turn out to be more resilient than expected. MacDonald and others, though, are concerned about possible water contamination since greater rainfall intensity can flood septic tanks, sending the contaminants into aquifers. While groundwater may not be depleted by climate change, more people are using it, which is good for public health but a risk for long-term sustainability.

“That’s something we’ll need to watch,” MacDonald said.

Learn more about how GIS is applied to manage water resources.

September 24, 2019 |

August 25, 2020 | Multiple Authors |

September 10, 2019 |