June 13, 2019 | Multiple Authors |

June 9, 2020

Famous for its fishing villages and resort hotels, Cape Cod is an iconic spot for summer vacationers. The Cape also forms one of the world’s largest barrier islands, protecting the rest of the Massachusetts shore from violent northeaster storms—but today, those world-famous shorelines are slipping away.

Wind and rain have always worn away at the cliffsides and shores of Cape Cod’s 130 beaches, causing natural coastal erosion. The waterfront undergoes a continual process of reshaping, with sediment washing away and depositing anew. In recent years, however, climate change has accelerated this process, and the protective shield of Cape Cod now needs protection of its own.

“Cape Cod is facing significant risks from sea level rise, from storm surge, from erosion, and they’re getting more significant and more extreme,” said Kristy Senatori, executive director of the Cape Cod Commission. “We have over 586 miles of vulnerable shoreline that can be impacted.”

The Cape Cod Commission, formed in the 1980s, works to protect the peninsula’s uniqueness and quality of life. The commission got its start when the alarming pace of development threatened to overwhelm and deplete the Cape’s only source of freshwater. It now handles regional planning, economic development, and regulatory measures, balancing environmental protection with economic progress.

As climate change threatens the area, the commission is focusing on resilience.

“We look at the Cape in terms of systems,” Senatori said. “We look at impacts to economic systems, environmental systems, and community systems.”

To understand how these systems are connected, the commission uses a geographic information system (GIS). The GIS and Geodesign department applies the principles of geodesign to analyze and present different planning scenarios that take into account current ecological and infrastructural vulnerabilities. Put simply, geodesign provides the framework for testing alternatives, evaluating their impacts, and visualizing their outcomes. Geodesign is data-, evaluation-, and impact-driven design.

One example is bridges. There are just two vehicle bridges providing access to and from Cape Cod. The integrity of the Bourne and Sagamore Bridges is essential to the daily lives and safety of residents, yet both were built in the 1930s and have exceeded their intended life-span. While plans are under discussion to upgrade or replace these bridges, climate change makes them more vulnerable. If either or both bridges were damaged during a severe storm, residents would not be able to get out, and emergency personnel would not be able to get in.

In 2016, growing evidence of the local impact of climate change urged the commission into action. Some residents, for instance, had already built seawalls of stone or sand to protect the shore near their homes. While these individual efforts demonstrated spirit and ingenuity, they came at a cost to the beaches downstream, where sands could no longer travel.

A more holistic approach was needed to identify solutions that would be equitable for everyone and every locale—for the 215,000 full-time residents as well as the 38 percent for whom the Cape is a second home.

With the assistance of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA)’s Regional Coastal Resilience Grant program, the commission launched the Resilient Cape Cod project. To start, it researched various coastline preservation strategies that have been developed around the world.

These strategies fall within three broad approaches—those that protect, those that accommodate, and those that retreat. Protection-based strategies—like creating a living shoreline by adding natural materials to form a barrier that grows over time—focus on shielding the diminishing beach from the waves. Accommodation strategies, including marsh restoration, aim to mitigate local hazards by modifying existing natural systems or infrastructure. Retreat strategies focus on removing built structures and facilities from the advancing tide line.

The next step was to present options and listen to stakeholders. Local engagement was key, with regular community meetings held over several years to discuss mitigation and adaptation options. Once the group determined viable options, the commission organized the information in an Adaptation Strategies database, which was made available at the Resilient Cape Cod project website.

“The strategies all have a fact sheet that accompany them,” Senatori said. “It looks at the costs and at the scale—deployable at a site, a neighborhood, or the region—and it also includes some of the advantages and disadvantages of using that particular strategy.”

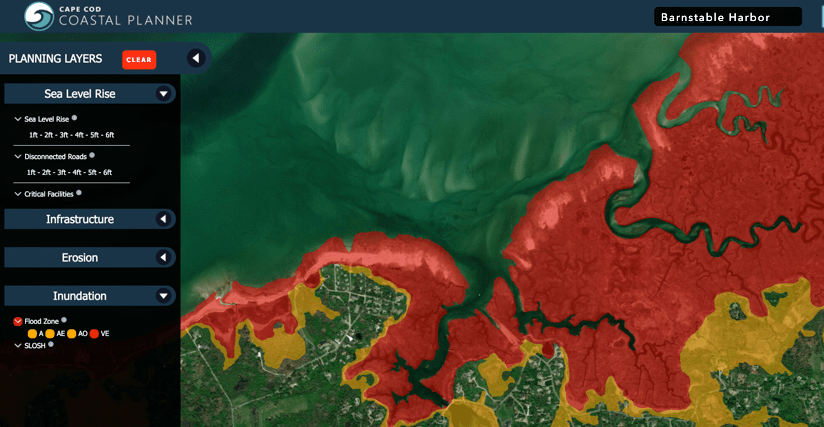

To engage the community in the Resilient Cape Cod project, the commission needed a way for people to explore the strategies and weigh potential benefits or costs. It developed the Cape Cod Coastal Planner, an interactive, online application residents can use to visualize the local impact of sea level rise and erosion, along with different mitigation approaches. The app encompasses all 15 communities of Cape Cod, transcending community boundaries to include affected areas of this diverse region.

Users of the Cape Cod Coastal Planner can select the shoreline stretch that most affects their home, then see a vulnerability level for every spot along that area of the coast. They can explore anticipated effects of sea level rise, locations of critical facilities and infrastructure across the area, and predictions of future erosion or sediment movement. The tool also identifies flood zones and SLOSH (Sea, Lake, and Overland Surge from Hurricanes) potential for category 1, 2, 3, and 4 storms.

The Cape Cod Coastal Planner presents mitigation techniques including beach nourishment (to add sediment directly to the beach), living shoreline formation, dune creation, undevelopment (to remove existing structures from eroding areas), and even inaction—to simply do nothing. Each strategy layer includes an estimate of approximate cost to implement, the expected life-span of the project, and the impact on the local ecosystem.

“The online decision support tool that we created is a communications platform as well as a decision support tool,” Senatori said. “It’s an opportunity for us to educate stakeholders about the different adaptation strategies . . . and also to have decision-makers understand some of the trade-offs.”

In addition to aiding individual awareness, the Cape Cod Coastal Planner is supporting town leaders who must create comprehensive plans.

“We piloted the planner in the town of Barnstable,” Senatori said. “It’s been a really great opportunity for stakeholders to explore the impacts of certain strategies and to see what they would actually look like. It’s been really effective as a communication tool.”

As the largest town in Cape Cod and one of the most vulnerable to erosion on the northern side of the Cape, Barnstable was a natural choice for the pilot project. The commission held community meetings and workshops to discuss strategies and used the planner to compare scenario outcomes. Attendees also provided valuable feedback on future planner updates.

The pilot project helped Barnstable residents understand their weaknesses and strengths; vulnerabilities to coastal erosion, sea level rise, and severe weather events are balanced by the town’s public safety assets such as the regional Cape Cod Hospital, two airports, a regional emergency shelter, and an advanced emergency alert system.

Moving forward, the commission is continuing to develop tools that help residents understand environmental risks and trends. Currently, efforts are underway to map historic storm paths to better predict and plan for future storm events.

“The State of Massachusetts has really taken a leadership role in coping with climate hazards,” Senatori said. “I think it’s only a matter of time before we have another hurricane that could be potentially catastrophic for our region, and we’re going to be prepared when the time comes.”

Learn how geodesign provides a framework and tools for design and planning that more closely follow natural systems.

June 13, 2019 | Multiple Authors |

August 3, 2018 |

May 14, 2019 |